Features

Hesitation was never something that could hold singer Sandy Stewart back—not when it came to her career. The...

Bistro Bits: A New Album from D.C. Anderson and a Lina Koutrakos Trifecta

In this column, I check in on an important new album from singer/songwriter/actor D.C. Anderson. Plus, I report...

SEE MORE FEATURES

Club Reviews

Clint Holmes— “Icons Reimagined”

It’s the real thing. Coca Cola made that slogan (and an accompanying jingle) widespread at the beginning of...

“Josh Johnson’s Garden Variety Show”

Josh Johnson, one of the freshest, funniest young comics around, is familiar to many from his regular contributions...

“I Wish You Love: The French Songbook with David Marino”

I Wish You Love: The French Songbook with David Marino is a beautifully crafted, wonderfully performed showcase for...

SEE MORE CLUB REVIEWS

Album Reviews

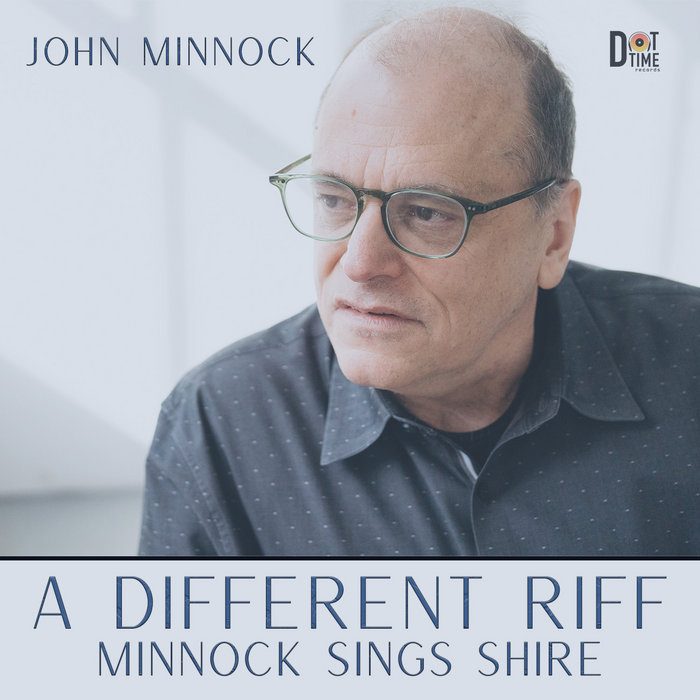

Bistro Bits: Special-Case Albums—New Releases by Minnock and Aloisio/Pallatto

Today for Bistro Bits, I’m having a look at two recent album releases, both of which fall into...

Bistro Bits: Jazz Babies 2024–New Recordings by Russell and Mason, Loar, and Levy/Vannatter

A couple of weeks ago, writer Lisa Jo Sagolla discussed a number of new recordings on this site....

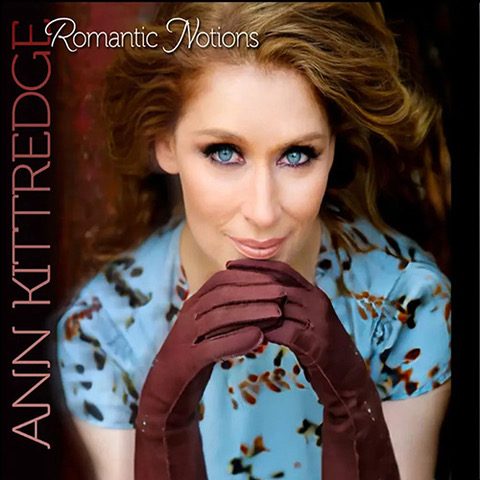

Album Reviews: A Pleasurable Trio of Recent Releases

Reviewing recordings by leading cabaret vocalists may be the heavenliest job on earth, as this latest batch of...