Features

Bistro Bits: A New Album from D.C. Anderson and a Lina Koutrakos Trifecta

In this column, I check in on an important new album from singer/songwriter/actor D.C. Anderson. Plus, I report...

Crowdfunding: The Do’s, the Don’ts, the Virtues, the Liabilities

Doing What You Have to Do to Get Your Work Out There When James Beaman decided to return...

SEE MORE FEATURES

Club Reviews

Bistro Bits: Winter Rhythms 2024 Features Beats of Different Drums

This year’s “Winter Rhythms” series at Urban Stages (the 16th annual edition) was a mix of old and...

A Grab Bag of Cabaret Shows in a Wide Array of Styles

It seems each year the holiday season starts earlier and gets here quicker, and inevitably leaves me with...

SEE MORE CLUB REVIEWS

Album Reviews

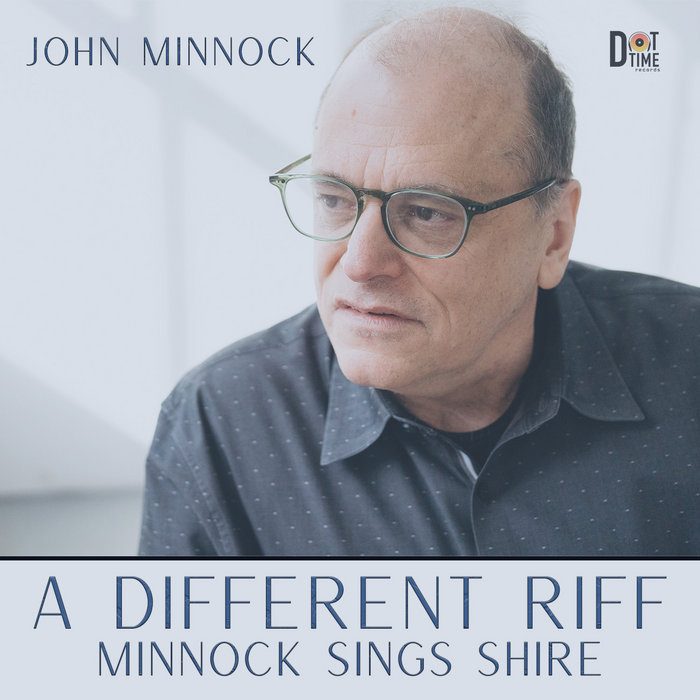

Bistro Bits: Special-Case Albums—New Releases by Minnock and Aloisio/Pallatto

Today for Bistro Bits, I’m having a look at two recent album releases, both of which fall into...

Bistro Bits: Jazz Babies 2024–New Recordings by Russell and Mason, Loar, and Levy/Vannatter

A couple of weeks ago, writer Lisa Jo Sagolla discussed a number of new recordings on this site....

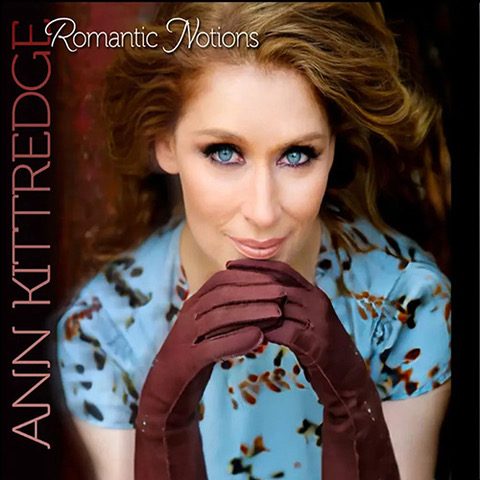

Album Reviews: A Pleasurable Trio of Recent Releases

Reviewing recordings by leading cabaret vocalists may be the heavenliest job on earth, as this latest batch of...