Cabaret Setlist: “Everybody Gets to Go to the Moon” — Music and Lyrics by Jimmy Webb

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Article # 18 in this ongoing series.

With richer-than-God entrepreneurs—Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Richard Branson—pioneering commercial flights into space these days, the rocket-ship dreams that people harbored back in the early days of the international Space Race have been reignited. (Such fantasies will seem more attainable, of course, if you, too, happen to be wealthier than the Almighty.)

On September 15, Musk’s SpaceX company launched four Americans into the blue for the first orbital flight crewed by tourists. With this threshold crossed, how long will it be before civilian earthlings have their eyes on lunar voyages?

Not long at all, apparently. Earlier this year, the announcement came that Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa will select eight passengers for a SpaceX flight orbiting the lunar globe in 2023.

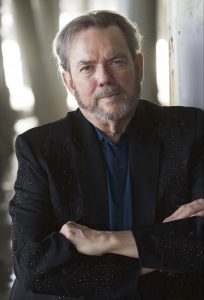

All this may be good news for singer-songwriter Jimmy Webb. In 1969, the year when the Apollo 11 crew—Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins—first put human boots on the lunar surface, Webb introduced a lively and lovably nutty song called “Everybody Gets to Go to the Moon.” It’s not up there with “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” or “MacArthur Park” in the Jimmy Webb hit parade. But it’s a song worth a revisit—and, perhaps, a significant revival.

“Everybody Gets to Go…” made a deep impression on my 15-year-old brain when I first heard it at the time of the Apollo 11 flight. I recall a female performer—I don’t remember who—singing it on one of the weekday-afternoon TV talk shows helmed by either Merv Griffin or Mike Douglas. After a single hearing, I could remember and even sing much of the exuberant melody and amusing lyric. The song has stuck with me for decades, so it’s been great fun taking a deeper look at it. Before we examine the song more closely, first listen to Thelma Houston‘s version of it here:

Lunar Tune

Webb’s rousing, up-tempo arrangement of the song opens with instrumental fanfare suggesting horses carrying Ben Cartwright and his sons across the Ponderosa, dust billowing behind them. (Space is the “final frontier,” remember?) This figure is repeated throughout the song, and, in most recorded renditions, it ends each time with notes from a horn that sounds like a bugle announcing the arrival of the cavalry.

Webb’s song contains three verses, each followed by a refrain plus a sung interlude that begins with the lyric “Isn’t it a miracle that we’re the generation…?” This section ends with the climactic: “It has to make you proud to be a man…” preceding the final verse and refrain.

The lyrics are playful, whimsical—sophisticated yet colloquial. Each verse begins with the words “How many times…” which helps set up a sense of balance and anticipation. The repeated lines (from the refrain) beginning “It’s customary in songs like this…” take the number into “meta” territory. This song is fully aware that it’s a song—specifically, one of scores of moon songs from the American Songbook. The clever Webb simultaneously acknowledges the clichéd “moon-June-spoon-croon” rhymes in such songs and happily adopts them for his own purposes.

In the first verse, the singer describes being “downhearted”: looking up at the man in the moon, wondering why he seems so consistently happy and why he can’t always hover above to reveal the secret of his contentment? He or she wishes to “catch a flying horse” to meet up with him. The first iteration of the refrain announces the big breakthrough: thanks to NASA, humankind can, in fact, saddle up and reach the once-impossible target.

In the second verse, the tables turn. Now the singer has decided that Moon Man may not be so contented after all. Perhaps he’s fascinated with (and envious of) the humans he looks down upon, the ones singing songs about him. He may crave their company (especially since the unexplained departure of “the lady in the moon,” a character not alluded to in preceding or subsequent lines).

The “interlude” section is devoted to celebration of the fact that people living in 1969 will be the first to “touch that shiny bauble with our own two hands.” The final verse, in which the singer copes with naysayers, has the trickiest lyrics:

How many times have I heard a cynic

Say I was a fool to try and reach for him?

Or heard a dreamer say, “The sky’s the limit”

And had to laugh at each for him?

I understand the first two lines, but I have to strain a bit to get the gist of the third and, especially, the fourth. My best paraphrase would be, “I’ve had to laugh at both cynics and dreamers on behalf of my pal the moon.”

Then Webb wraps things up:

I suppose the point is only

That an old friend is no longer lonely.

The moon’s in his heaven. So are we. And all’s right with the world.

Houston, We Have a Project

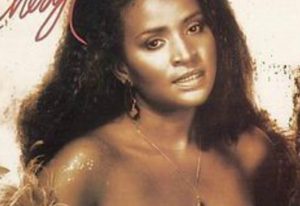

The logical sources to start with in writing about this song’s history are the man who wrote it and the woman who first sang it. So, I was thrilled when both Jimmy Webb and Thelma Houston agreed to speak with me.

Webb composed the song for Houston’s first album, Sunshower (ABC Dunhill), which he also produced. Work on the album began in Los Angeles in 1968. The recording was released the following year.

Houston remembers being introduced to Webb by producer Marc Gordon. “Jimmy said, ‘Well, who’s producing her?’ And Marc said, ‘Well, you can produce her if you like.’ And that’s how that happened.”

Aside from a cover of the Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” all the songs on the Sunshower album were written by Webb, some of them completed during the making of the album. From the start, Webb was impressed by Houston—both as a performer and as a person. “She was a joy. She was a sun shower. She was just a wonderful person to be around—and still is…. I’ve always thought she was in the same realm as Aretha Franklin. And I don’t apologize for that.” (In 2020, Webb and Houston teamed up again for the reboot of another song from Sunshower, “Someone Is Standing Outside.”)

In both his youth and his adulthood, Webb has been intrigued by all things space related. “I followed the Apollo program faithfully….” he says. “I was a science-fiction kid. I grew up on Ray Bradbury, [Isaac] Asimov, [Robert] Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke.” Anticipation about the scheduled moon landing was growing while he and Houston worked on Sunshower. The Apollo 10 mission—in which astronauts orbited the moon in a trial run, just short of an actual lunar landing—had used Webb’s first monster songwriting hit, the Fifth Dimension’s “Up, Up and Away,” as wake-up music for the flight crew. (His song “Galveston” would be on Buzz Aldrin’s personalized playlist during the Apollo 11 mission.)

As the upcoming moon landing occupied people’s thoughts, Webb decided to mark the occasion. “I thought, I’m gonna write a moon song. That’s what songwriters do.”

Webb embraced Robert Heinlein’s idea that space exploration would include a civilian presence. But he treated that idea in lighthearted fashion with his song. “I was also being a little silly at the time: ‘OK, we’re all going to end up going to the moon now.’”

At the time the album was recorded, Houston was living in Long Beach, CA, while Webb had a penthouse in a Los Angeles building at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue. She recalls: “He would send his driver to pick me up, or he would pick me up down in Long Beach ’cause I wasn’t driving, bring me up to Los Angeles to rehearse the songs we were gonna sing the next day at the studio.”

She laughs now at her own audacity in working with Webb. “Jimmy would say, ‘What do you think about this song?” And I would say, ‘Hmm, I don’t know about that one.’ In my mind, I thought, Thelma, did you actually turn down a Jimmy Webb [song]? But he never imposed a song on me. If I didn’t feel a connection to the song, then we didn’t do it.” She didn’t at all care for the “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” cover, which she found too “grimy” and “gritty.” “I don’t even know what that song was about. But he loved that song. And I said, ‘OK, Thelma….’ Even in my naiveté, somethin’ said to me, ‘Now, look: Don’t be an a-hole. If the man wants you to do this one song, you can make that concession.’” (In subsequent years, Houston grew to appreciate her rendition of the classic rock title.)

She recalls the specific work on “Everybody Gets to Go…”:

“Jimmy has always liked fast things. He likes planes, he likes fast cars. So, we would be practicing our song. We would take a break and we would throw those little model airplanes that you make out of balsa wood…out the window and we would laugh.” (Webb corroborates Houston’s story, though he remembers paper airplanes launched from the roof. “Sometimes they’d go for miles. ’Cause I make a mean paper airplane.’”

Making the Cut

The recording of the song (and of the whole Sunshower album) took place at Armin Steiner’s Sound Recorders studio in Los Angeles and featured a group of exceptional musicians. “I remember going in with The Wrecking Crew and cutting the basic track and then laying down an instrumental section because the studio wasn’t quite big enough for a full orchestra. I put strings and horns in later.”

He was particularly happy with the arrangement he’d created for “Everybody Gets to Go…” “Paul Shaffer told me once that it was the best arrangement I ever did.”

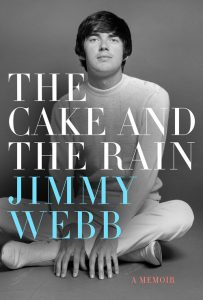

There were so many takes on some songs that Webb got in trouble with the label’s money men (something he describes in his 2017 memoir, The Cake and the Rain). But there were times when something would happen in the studio that was spontaneous and brilliant, something that was best left alone, free of further fussing. Such was the case with the last part of “Everybody Gets to Go…” into which Houston and the musicians interpolated a bit of “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” (Gus Edwards, Edward Madden/1909), the title of which is referenced in Webb’s lyric. This passage has a comedic, old-timey “red-hot Mama” vibe, replete with kazoo sounds, bumps and grinds, grunts and giggles.

There were so many takes on some songs that Webb got in trouble with the label’s money men (something he describes in his 2017 memoir, The Cake and the Rain). But there were times when something would happen in the studio that was spontaneous and brilliant, something that was best left alone, free of further fussing. Such was the case with the last part of “Everybody Gets to Go…” into which Houston and the musicians interpolated a bit of “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” (Gus Edwards, Edward Madden/1909), the title of which is referenced in Webb’s lyric. This passage has a comedic, old-timey “red-hot Mama” vibe, replete with kazoo sounds, bumps and grinds, grunts and giggles.

“The last part of the song was all ad lib,” Houston says. “I was just being silly with the musicians.”

Webb has happy memories of the day this happened:

“They were just acting silly, and I thought, you know, Damn, that’s absolutely great! And I asked Thelma: ‘Do you think you could learn ‘By the Light of the Silvery Moon’? I want to put it at the end.’ So, she went off and got the lyrics and learned it and came in and just pushed the button and overdubbed it to the tail end of the fade.”

I ask Houston about one particular lyric in the song, which seems, perhaps, not to have withstood the test of time. It comes in the last lines of what I’ve earlier referred to as the “interlude” section:

Isn’t it a miracle that we’re the generation

Who will touch that shiny bauble with our own two hands?

It has to make you glad to be alive.

It has to make you proud to be a man.

Certainly, when he wrote this lyric, Webb meant “man” to stand in for “human.” But to ears in the early 21st century, the line may come off as male-centric.

Houston stands by the lyric.

“We all understood that when they said ‘man,’ it meant ‘mankind.’ We didn’t put too much bullshit on it—excuse my word…. To me, ‘man’ meant ‘mankind,’ and ‘mankind’ means ‘man and woman.’”

Sunshower didn’t sell well, but it has always had a solid reputation with pop-music critics. Webb says it’s one of the best albums he’s ever been involved with. “It didn’t get the send-off we would have really liked, but it quickly became a kind of underground classic—and still is.”

Houston—who, of course, went on to enormous success in the disco era with “Don’t Leave Me This Way”—says she still sings “Everybody Gets to Go…” in her live shows.

“I don’t do it all the time,” she adds. “I like it when there’s a full orchestra.”

Her advice to someone thinking of performing the number: “It’s a lot of words. Make sure you enunciate and take big breaths. Just have fun with it. That’s all.”

Webb has never sung the song himself, but he thinks doing so now is not such a bad idea, especially with the renewed interest in commercial space travel (something he would like to participate in himself). When I tell him that some cabaret singers in New York City perform the number these days, he tells me that cabaret is the right “milieu” for the song.

“Its roots are in show tunes,” he explains. “It would have made a great show tune for a musical about Jules Verne.”

Funky NASA

As mentioned earlier, most of the covers that followed the Webb/Houston collaboration have stayed very close to the sound of the original. Almost all versions have been sung by women. These include a strings-suffused version by Judy Singh (1970) and a brassy iteration by Sheila Southern (1992).

Leslie Uggams belted the song enthusiastically in a clip that’s been identified as part of the final episode of her 1969 TV variety hour. Webb’s rhythmic pulse here has been adjusted slightly. It sounds very much like one of Burt Bacharach’s go-to beats. Uggams repeatedly sings a wrong lyric that threatens to turn the song from celebration to lament. Instead of “Everybody gets to go, it will be quite soon,” she sings, “Everybody gets to go but me, quite soon.” Uggams also attaches her own rendition of Houston’s “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” ending, including a very Houstonian grunt. Listen here.

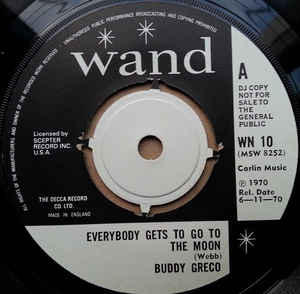

The only widely known version of the song that was recorded by a male performer is this one by Buddy Greco, also from 1969. Notice that he changes the moon’s gender to female on verses 1 and 3 but keeps the character male on verse 2 (which mentions the absence of the Lady in the Moon). Listen to Greco’s version here.

The only widely known version of the song that was recorded by a male performer is this one by Buddy Greco, also from 1969. Notice that he changes the moon’s gender to female on verses 1 and 3 but keeps the character male on verse 2 (which mentions the absence of the Lady in the Moon). Listen to Greco’s version here.

In an audio recording of a 1969 live concert version of the song, Dusty Springfield—like Uggams—included her own raucous bit of “By the Light of the Silvery Moon.” But in 1970, when she performed the number on Engelbert Humperdinck’s TV variety show, she dropped this, along with the song’s second verse and chorus. She also changed “It has to make you proud to be a man” to a variation on the previous line: “It has to make you proud to be alive.” We thereby lose a rhyme. Or maybe not. Webb’s pairing of “hands” with “man” was actually more assonance than rhyme to begin with. Hear the difference here.

Part of the Three Degrees version is heard in William Friedkin’s Oscar-winning The French Connection—part of a nightclub scene. The trio introduces some pleasing harmonies, but the rendition may be a little over-frenetic for some people’s tastes. Webb believes the group“ nailed the song,” but he tells me he didn’t know the filmmakers had used it until he saw the movie. He wonders if there was some “veiled message” from Friedkin in the song’s use, having to do with the film’s drug theme. Could “going to the moon” be a reference to getting high? Listen to it here with a new perspective.

Cheryl Barnes, in 1987, was perhaps the first artist to experiment with changing the whole soundscape of the song. She drops the galloping intro and bugle effects and makes the tune a relatively laid-back, conga-ish confection. In my opinion, this impulse was a sound one. It remains for future performers, though, to come up with other viable reimaginings of the song. Here’s Barnes’s version.

New Moons

NYC singers Lauren Mufson and Natalie Douglas came to Webb’s song by way of the late musical director and vocal coach Stephen Bocchino, who was an admirer of Jimmy Webb’s music. Mufson recalls working with Bocchino at Brandy’s Piano Bar in the late 1980s:

“Many of the cabaret folks he worked with would come in and sing. I don’t recall who I first heard sing it, but I remember thinking it was such an odd pop song: the lyrics had this very tongue-in-cheek quality while the rhythm was like a jazzy runaway train. I did not want to sing it but admired the joy it conveyed.”

Later, Gerry Geddes asked her to perform the number as part of a Jimmy Webb tribute show at Eighty Eight’s in the West Village, with Gerry Dieffenbach as musical director.

“I thought, ‘Oh, boy, this song, how am I going to do this crazy song?’ Gerry Dieffenbach went over the rhythm with me in rehearsal and, man, it’s not easy. I remember obsessively going over it in my head, falling asleep with my thoughts manically shifting between 4/4 and 3/4.”

Eventually, she got the hang of it, and she and Dieffenbach found a fairly “straightforward” arrangement. “It was probably most like the Dusty Springfield version minus the large orchestra. Gerry D. plays piano like an entire band. He sounded great on it. Gerry Geddes helped me focus on the wonder and humor of it all.”

The work, says Mufson, paid off. “I actually can’t believe how well it was received. The song is of a very specific time and place, so I wondered whether it was a bit dated. But it is inherently playful, joyful, cheeky. Add that to the rollercoaster feel of the rhythm—I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised.”

The song wasn’t entirely new to Douglas when Bocchino brought it to her. She remembers knowing about it as a child, and she believes her parents may have owned a copy of the Sunshower album. She found the rhythms “a bit tricky” to learn, but she grew to find them one of the most appealing features of the tune.

“One of the things I love about the song is how fantastically ’60s it is,” she says. “Of course, the topic could only be of that particular moment. I mean, [Webb] wrote it with lyrics about how we hadn’t touched the moon yet, but we would soon. Furthermore, I think the groove and the poetry are exceedingly period.”

But she finds a culturally relevant aspect of the song for 2021 listeners: “There’s something so optimistic about the ’60s Space Race. I don’t think it’s only coincidence that optimism exists at the exact same time as so much progress in the civil rights movement, women’s rights, and the peace movement. The song is so full of joy and hope. I also really love a song that celebrates STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] achievements. And knowing how many Black women, in particular, were essential to the success of the moon landing makes it an even happier tune to me.”

Douglas has retained “Everybody Gets to Go…” as part of her permanent repertoire. In fact, she recently sang it this past September, with Mark Hartman at the piano, as part of the NiCori Music at the Mansion concert series in Bloomfield, NJ. Watch it here.

She often includes the number in her annual New Year’s Eve shows as well. “Seems we can all use a dose of optimism and joy as we approach the new year.”

Postscript: The Man in the Moon Is a Lady

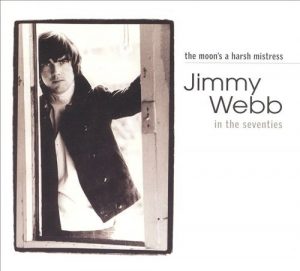

Jimmy Webb didn’t give up on the moon as muse after writing this song. In 1974, he created “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” which was originally recorded by Joe Cocker.

Jimmy Webb didn’t give up on the moon as muse after writing this song. In 1974, he created “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” which was originally recorded by Joe Cocker.

“That one I take a little more seriously,” he says. “I think that one’s more of a statement about life itself and the things that we aspire to. It’s important to [aspire to things], and it’s also important to know that you can’t always get what you want.”

In this number, he presents the silvery orb not as a friendly bloke but as a distant and cool female presence. The ballad has become a much more widely performed and recorded song than “Everybody Gets to Go…” ever was. Among those who’ve recorded it: Glen Campbell, Linda Ronstadt, Josh Groban, and Rumer, along with such Bistro Award recipients as Judy Collins, Michael Feinstein, Christine Andreas, Lee Lessack, Tom Wopat, and Sheila Jordan.

Let’s close this installment of Cabaret Setlist with Webb’s own version:

***

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.