Cabaret Setlist: “Lush Life” – Music and Lyrics by Billy Strayhorn

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Song #12 in this running series

Billy Strayhorn’s intricate ballad “Lush Life” has, I think, something in common with Stonehenge—England’s massive and mysterious Bronze Age monument. Both are remarkable accomplishments whose existence seems scarcely plausible. You can’t fully explain how they arrived or what inspired their creation. Yet there they are before us—unmistakably, gobsmackingly real.

Billy Strayhorn’s intricate ballad “Lush Life” has, I think, something in common with Stonehenge—England’s massive and mysterious Bronze Age monument. Both are remarkable accomplishments whose existence seems scarcely plausible. You can’t fully explain how they arrived or what inspired their creation. Yet there they are before us—unmistakably, gobsmackingly real.

A song of wistfulness and woundedness about a love affair that didn’t take, “Lush Life” would have been a fine addition to the American Songbook had it been written by the mature Cole Porter in one of his more pensive, worldly-wise patches. But that’s not the song’s origin story at all.

No, Strayhorn began writing “Lush Life”—which he initially called “Life Is Lonely”—when he was in his mid-to-late teens: a Black, gay kid living in Pittsburgh. The lyric proclaims that “a week in Paris will ease the bite” of a broken romance. Yet the precocious composer/lyricist—born in Dayton, Ohio in 1915—had, at that point, visited the City of Lights only in his imagination. If what Strayhorn accomplished with “Lush Life” is not evidence of a kind of genius, I’m not sure what we can call it. Hear for yourself the genius of Strayhorn.

Like a Prayer

The song’s unlikely genesis has certainly contributed to the mystique surrounding it. Before she performed the selection on Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz radio program in 2005, Linda Ronstadt referred to “Lush Life” as “a weird song” (because of Strayhorn’s precociousness in having written it), but she also proclaimed it her favorite “in all of the literature”—by which I assume she meant “in all of the catalogue of American standards.

The song’s unlikely genesis has certainly contributed to the mystique surrounding it. Before she performed the selection on Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz radio program in 2005, Linda Ronstadt referred to “Lush Life” as “a weird song” (because of Strayhorn’s precociousness in having written it), but she also proclaimed it her favorite “in all of the literature”—by which I assume she meant “in all of the catalogue of American standards.

Musically complex, lyrically rich, and emotionally harrowing, Strayhorn’s composition has a reputation as a kind of Mount Everest of song. Few singers would choose to scale it without some serious contemplation and preparation. It’s also a bona fide jazz classic, and if you’re not a jazz singer, its pedigree may make you especially wary. Ronstadt recorded it in 1985, as part of an album of the same name. After the album’s release, critic John Milward wrote that “Lush Life” was “like a final exam” for the pop singer. Milward felt that Ronstadt (with help from arranger Nelson Riddle) had aced that test. But others—including Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra—have by no means found “Lush Life” to be an easy “A”. Watch Ronstadt below, introduced by Joe Williams, at a 1998 show honoring Rosemary Clooney:

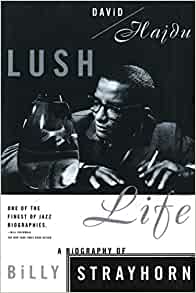

In his terrific 1996 Strayhorn biography—also called Lush Life (North Point Press)—writer David Hajdu describes the song as “a prayer.”

He notes that, in ensuing years—after Strayhorn had begun his long association with composer and bandleader Duke Ellington—the composer preferred to write quickly and without a lot of second guessing. But the creation of “Lush Life” was something else again. Strayhorn had built the song slowly—painstakingly, it seems—over a period of years (approximately 1933 to 1936, but perhaps beginning even earlier): expanding it, reworking it, embellishing it. And he treated it as a very personal thing. He kept the song out of the public ear for years after its completion, though he would sing and play it for friends at parties.

The song’s long incubation period seems to have coincided with Strayhorn’s unfolding cognizance of his identity as a gay man. Writes Hajdu of the song: “It is a masterpiece of fatalist sophistication that belies its author’s youth but betrays years of ferment…. From its opening lines, ‘Lush Life’ can easily be interpreted as an evocation of a homosexual experience….”

The song’s long incubation period seems to have coincided with Strayhorn’s unfolding cognizance of his identity as a gay man. Writes Hajdu of the song: “It is a masterpiece of fatalist sophistication that belies its author’s youth but betrays years of ferment…. From its opening lines, ‘Lush Life’ can easily be interpreted as an evocation of a homosexual experience….”

Still, Hajdu is not convinced that the very first lyric (“I used to visit all the very gay places”) is necessarily evidence of an adolescence lived openly in homosexual circles. He suggests that it’s doubtful that Strayhorn would have fully emerged from the closet in his middle-to-late teens or that he would have used the word “gay” in its sexual-orientation sense in those years.

Perhaps the “ferment” in Strayhorn’s early years centered instead on his uneasy relationship with his hard-drinking, abusive father—a man who certainly identified his son’s differentness and fumed against it, once even stomping on the boy’s eyeglasses. (To be clear, James Strayhorn showed cruelty to his other children as well.) Fortunately, young Billy enjoyed a close relationship with his mother, Lillian.

Remarkably, as Hajdu shows, Strayhorn appears to have emerged from his youth as a man at relative ease with his sexual identity. He would live openly and happily with a companion, Aaron Bridgers, for many years, and his gayness was accepted quite readily by his surrogate father figure, Ellington (although there were other dimensions of their relationship that were complicated if not bedeviling). Strayhorn was certainly acquainted with demons—most notably, a growing, inherited propensity for abuse of alcohol—but he did not wind up living out his life miserably “in some small dive” as the protagonist of “Lush Life” vows to do. Sadly, this may be in part attributable to the fact that he died so early—in 1967 at age 51, of esophageal cancer.

Complex Harmonies, Subtle Rhymes

“Lush Life,” as Hajdu puts it, “exquisitely weds words and music.” Listening to the many recordings of the song fully supports such a judgment.

I find it striking that the verse and chorus of the song seem to be equally important components. With other songs we’ve looked at in “Cabaret Setlist,” singers have often omitted the verse, but that seems almost unthinkable with this song. Has anyone ever sung the chorus of “Lush Life” alone?

The verse is actually the longer of the two sections, and it contains some of the song’s strongest lyrical ideas. The opening stanza is one long, winding perfect sentence, brimming with a bold metaphor and clever internal rhymes. Everything seems just where it ought to be:

I used to visit all the very gay places,

Those come what may places

Where one relaxes on the axis

Of the wheel of life

To get the feel of life

From jazz and cocktails.

The meandering quality of the notes and lyrics in this stanza and in the one that follows suggests a sort of anxious search for some kind of resolution. By the end of the second stanza, the sense that Strayhorn owes you a rhyme has almost been forgotten. But one arrives—satisfyingly—with the phrase “…too many through the day / Twelve o’clock tales.”

Both verse and chorus contain surprising harmonic turns. Musical analyst David Burt notes in the opening moments of his online “Lush Life” tutorial the premise that any chord can follow any other chord: “There’s no rule that says you can’t do that. And that was never truer than when William Thomas Strayhorn wrote ‘Lush Life.’”

Hajdu remarks on an “optimistic” key change in the chorus, occurring during the phrase “everything seemed so sure.” He notes the somewhat awkward lyric in the subsequent phrase, “A trough full of hearts / could only be a bore.” (Note: The lyric is often rendered in print as “a trough full of heart” (singular), but most singers—including Strayhorn himself—have sung “a trough full of hearts.”) Hajdu doesn’t point out the slant rhyme of “sure” with “bore” here, but it seems to me to have been an intentional choice. That Strayhorn didn’t find a perfect rhyme for “sure” is fitting for a narrative in which a love affair is seen as coming undone.

No matter how many times I listen to this song, I find its final moments genuinely shocking:

Romance is mush

Stifling those who strive.

I’ll live a lush life in some small dive

And there I’ll be while I rot with the rest

Of those whose lives are lonely, too.

The soul-broken protagonist here seems to be sliding from disappointment into despair and cynicism—plopping, finally, into a pit of decadence and decay. The rhyme of “mush/stif-” with “lush life” (like an earlier one: “Paris” with “care is”) is artfully concealed and may go unnoticed by some ears. The word “rot,” on the other hand, remains unrhymed. It stands out like an ugly yet necessary blot on the whole song. Strayhorn seems to be daring singers to choose between glossing over the word or barking it sharply, as though it were a curse.

Perhaps a key thing to listen for in any interpretation of “Lush Life” is what, exactly, the singer will do with that single, treacherous syllable.

Listeners may take some small solace in the song’s final words. If nothing else, the protagonist imagines finding solidarity with other lonely souls in their hell-like watering hole. But such a notion provides only cold comfort.

Those Who Strive

“Lush Life” had its public debut—at long last—at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 1948, when it was performed by vocalist Kay Davis, with Strayhorn at the piano. Fortunately, this premiere was recorded for posterity. Listen here for the presence of the Ellington orchestra, which makes itself known at the very end of the performance:

The first major record release of the song was by Nat King Cole the following year. Strayhorn was greatly displeased with this recording, which had been given a souped-up arrangement that, especially during the verse portion, seems patently bizarre some seven decades after the fact. Aaron Bridgers told Hajdu that Strayhorn was uncharacteristically livid about the Cole recording: “He was screaming, “Why the fuck didn’t they leave it alone?’” Hajdu notes that Strayhorn was also miffed that Cole had botched a few of the lyrics—for instance, singing “strifling” instead of “stifling.” Judge for yourself; listen to the King Cole Trio here.

A parade of singers and musicians recorded “Lush Life” in the 1950s and 1960, including such stellar jazz vocalists as Billy Eckstine, Carmen McRae, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald (who would record it a second time in 1974), Johnny Hartman (with John Coltrane on saxophone), and Nancy Wilson. Singers somewhat less closely affiliated with jazz—Sammy Davis Jr., Jack Jones, and Robert Goulet—also took a crack at it. Many of these performances can be found online. Here are a couple of the most-revered renditions—by Sarah Vaughan and Johnny Hartman with John Coltrane.

A parade of singers and musicians recorded “Lush Life” in the 1950s and 1960, including such stellar jazz vocalists as Billy Eckstine, Carmen McRae, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald (who would record it a second time in 1974), Johnny Hartman (with John Coltrane on saxophone), and Nancy Wilson. Singers somewhat less closely affiliated with jazz—Sammy Davis Jr., Jack Jones, and Robert Goulet—also took a crack at it. Many of these performances can be found online. Here are a couple of the most-revered renditions—by Sarah Vaughan and Johnny Hartman with John Coltrane.

With its saloon-song sensibility, “Lush Life” would seem to have been a sure bet for Frank Sinatra. The star singer did, in fact, attempt a recording of it, in 1958, although he found himself stumped by either the song itself, Nelson Riddle’s arrangement of it, or both. (Riddle was, reportedly, not on hand during the failed recording session.) Takes from the session were released in recent years, providing a fascinating glimpse of what Sinatra’s version might have been.

One of my favorite versions of the song is a quiet but eloquent live recording by Blossom Dearie. It’s worth a listen just for her flaring throb of vibrato on the word “cocktail.” But Dearie, too, found challenges with the song. Note in her spoken intro the confession that it took her eleven years to learn to play and sing the number.

Urbane Vibe

In more recent decades, “Lush Life” has been sung by pop singers—not just Ronstadt but also such diverse talents as Donna Summer, Patti LuPone, Queen Latifah, Lady Gaga, and Barry Manilow. Along the way, a number of Bistro Award recipients have also performed and/or recorded it. I checked in with three of them about their own journeys with the song.

Darius de Haas grew up in a musical family: son to bassist Eddie de Haas and singer Geraldine de Haas. He remembers hearing “Lush Life” from about the age of six. His uncle, singer Andy Bey, would record the song, in 1991. De Haas himself first performed it at Chicago’s Boombala Club in about 1989, when he launched his career as a cabaret performer.

The song carries great personal significance for the singer, especially “at a time of great division in our country, where Black people are still fighting for equality.” Strayhorn himself had been part of that ongoing battle. The composer became more politically involved near the end of his life, even forging a friendship with Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I can only imagine,” de Haas continues, “what he had to navigate in terms of homophobia and discrimination, not only in certain musical circles—though Ellington and musicians in general loved and greatly respected him—but also just being a Black gay man in America at that time. Sounds cliché, but I, though not a songwriter—at least not yet—stand on his great shoulders.”

De Haas’s connection with the song has deepened over the years. In 2001, he performed a concert of Strayhorn music as part of Lincoln Center’s “Songbook” series. He repeated that show in a three-week gig at Arci’s, and then recorded “Lush Life” and other Strayhorn songs for his first CD, Darius de Haas: Variations on Strayhorn (PS Classics).

The piece has never been an easy one for him to perform. “It’s a very hard song—technically, musically, and emotionally—and, in my opinion, can come off very ‘put on.’ But I also think that the beauty of singing any great song over time is that you can discover and invest and grow into it…. My approach to singing it has definitely evolved. And I’m lucky to still sing it in different settings. I most recently performed it with the Boston Pops.” Here’s a sample of the song. The CD is available on Apple Music and elsewhere.

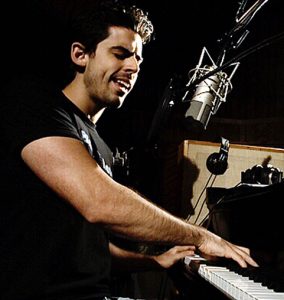

Singer and pianist Tony DeSare first worked on the song a few years ago, when planning a show at 54 Below for which he wanted “a sophisticated, urbane vibe.” He hired his childhood friend Tedd Firth as guest pianist, knowing that the two of them could bring something to the rendition that he alone could not pull off.

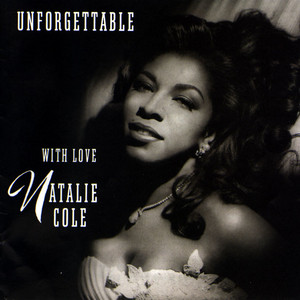

He had first heard the song as sung by Natalie Cole, who had recorded it in 1991—decades after the release of her  father’s controversial rendition. DeSare says he will “always be partial” to the younger Cole’s version: Listen to her here.

father’s controversial rendition. DeSare says he will “always be partial” to the younger Cole’s version: Listen to her here.

“The sheer beauty of the melody and lyric attracted me to the song,” says DeSare. “I think my first attempts at singing it were just to see if I could navigate that famously tricky melody. As far as how my interpretation has changed, it really depends on the specific settings and moments [in which] I’ve had the opportunity to perform this live with Tedd over the years. He is so inventive and spontaneous in his playing that different aspects of the emotion and beauty of this great song emerge based on Tedd’s and my in-the-moment interaction.”

Cautionary Tale

The third Bistro Award honoree I consulted has had one of the longest connections to “Lush Life” of any living vocalist. Veteran jazz singer Sheila Jordan began presenting the number in Greenwich Village venues in the 1950s. She believes her first performance of it was at a club called Page Three, where she was accompanied by pianist Herbie Nichols.

She doesn’t recall exactly when she first became aware of the song, but she remembers that she’d heard it played without vocals at first, and she was struck by its hypnotic melody. Later someone shared Strayhorn’s lyrics with her, and they had a deep effect on her personally. “I identified with it, because I have the problem of alcoholism,” she says. “I’m a recovering alcoholic.”

Jordan grew up in a family plagued by this affliction—it laid low her maternal grandfather, and it would kill her mother at a tender age. Jordan herself had had a bout of drinking during her high school years, though by the time she started singing in clubs, she was staunchly “anti-alcohol.” When customers would buy drinks for her and her musicians, she would spit hers into the chaser glass. But because her drink of choice was the conspicuously red “Cherry Heering” liqueur, she was soon found out. Embarrassed, she began imbibing in earnest. “It started me off…” she remembers. “It set off a craving.”

She saw both her mother and herself in the protagonist of “Lush Life.” The song became a cautionary tale for her, although she only partially heeded it during those early years. When she performed the number, however, it affected her deeply. “I remember singing it one time and I left my body. You know, I had an out-of-body musical experience.”

Jordan didn’t find the number difficult to learn. “If I love a song, then I just keep on it until I get it,” she told me. If she finds she has developed a perception of a song as difficult, then she loses “the respect and feeling of it.”

She recorded “Lush Life” in 1977, while in Europe. She included it in an album on the Steeplechase label in which she teamed with Norwegian bass player Arild Andersen. The opportunity to make this album came, she explains, at a point in her life when she was considered “a pioneer of bass and voice.” As a career-long proponent of the Charlie Parker school of jazz, however, Jordan’s greatest musical interest has long been bebop. She notes that some bebop instrumentalists have successfully performed their own renditions of “Lush Life.”

Thirty-five years ago, Jordan, with the help of a support organization, stopped drinking. “When I sing ‘Lush Life’ [now],” she says, “I remember all those times…it’s a part of my life. Every song I sing has to be something that I identify with. I don’t sing songs with lyrics that don’t touch me or that I can’t respond to. ‘Lush Life’ was very, very personal—yeah.”

Knowing the Territory

If you’re a singer who’s inclined to sing this complex and demanding song—even if you don’t have verified jazz chops—how should you proceed?

De Haas doesn’t think that jazz “cred” is necessarily the most important element in success with the number. He has enjoyed listening to versions of it by non-jazz artists, including Donna Summer and Rickie Lee Jones.

He does believe one needs to have reached a certain level of vocal proficiency to succeed with the song. When he auditioned for Off-Broadway’s Running Man (a 1999 production that would earn him an OBIE Award and greatly advance his theatrical career), the composer of the show asked him to sing two songs: “The Star-Spangled Banner” (to test his range) and “Lush Life” (to gauge his “musicality”).

“I would say, if you have a desire to sing ‘Lush Life’… learn the technical aspects of it, so it won’t be as daunting as you layer on the performance of it…. I would say practice, practice, practice. If need be, put it down and move on to something else….and then go back to it with a refreshed perspective. Sometimes it takes years—as Blossom Dearie said—before you can confidently perform it.”

DeSare believes that no song is necessarily off limits to anyone. He feels, though, that an audience can give you necessary cues as to whether “Lush Life” (or any song, for that matter) is right for you. “If I try a song a few times live, and I feel the audience not connecting to it, I either question my approach or question whether I should be singing the song at all.”

Of course, if you don’t have a regular outlet for testing material in front of an honest but nonjudgmental audience, the tack DeSare suggests might not be feasible. But cabaret open-mic events—such as NYC’s Salon—could be a good option (post-pandemic, that is) for trying out challenging material.

You’ll also want to consider, of course, exactly where, within a larger program, “Lush Life” should be slotted. Wedging what Hajdu refers to as a “darkly majestic” song like this one between such romance-positive titles as, say, “Thou Swell” and “I Got Lost in His Arms” would likely be jarring, especially if there is no spoken patter between the numbers to link them in a logical way.

Sheila Jordan believes that anyone attempting “Lush Life” must have some experience with the “lush life” itself: the emotionally hazardous milieu of small dives—where booze flows all too freely—inhabited by “those whose lives are lonely.”

“I don’t think it’s one of those tunes that you can just throw off….” she says. “You need to know what [the song is] about in order to sing it—and get it across— ’cause it’s a heavy message.”

Nevertheless, she hopes that vocalists will continue to want to sing the song:

“It’s a tune that we need to keep alive. It’s very important. More so now than ever.”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.