Cabaret Setlist: “When I Was a Boy” — Music and lyrics by Dar Williams

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Song #9 in this running series

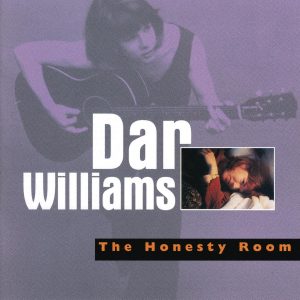

Although Dar Williams’s song “When I Was a Boy” would go on to become a signature number for her, she once apparently harbored doubts about its potential. This eloquent and extremely likable story-song might well have been laid to eternal rest in the singer-songwriter’s file cabinet. Instead, it became the opening track of her breakthrough CD—1993’s The Honesty Room.

Although Dar Williams’s song “When I Was a Boy” would go on to become a signature number for her, she once apparently harbored doubts about its potential. This eloquent and extremely likable story-song might well have been laid to eternal rest in the singer-songwriter’s file cabinet. Instead, it became the opening track of her breakthrough CD—1993’s The Honesty Room.

The song certainly fits with the title of that album. At its core, it’s a song about being truthful—with oneself and with others. Williams provides a first-person narrative in which the speaker reflects on her rowdy, tomboyish childhood. She harbors bittersweet, nostalgic feelings for her carefree past: the long-gone days when she could thumb her nose at those who questioned her flagrant disregard for norms of gender behavior. Near the end of the song—frustrated and caught off guard—she tells her male companion about those bygone days “when I was a boy.” It’s a potentially hazardous confession. And she delivers it with a wave of the white flag: “…I say, ‘Now you’re top gun./ I have lost and you have won.’”

The companion, however, turns out to have a confession of his own. The conclusion of “When I Was a Boy” delivers an optimistic burst of mutual understanding. Hear both confessions as Dar Williams sings the song below:

Birth of a Modern Standard

In a 2014 interview with Jim Ryan of Chicago at Night, Williams described how, soon after writing the song, she shared it with a friend who “was like a radical feminist.” The friend’s response was not what she’d hoped for:

“She said, ‘Oh. Well, I don’t like that song. I don’t like that it ends with a guy. Why couldn’t it just be about women?’ And I thought, ‘Well, you know…’ And again, this is who I was. I was like, ‘This is the truth for me.’ I didn’t really want it to be a breast feeding, feminist song. I mean, I could do that! And I love those songs. But this wasn’t [that kind of] song. It was a song about childhood and what we lose along the way by having to assign ourselves to various genders more specifically than we want.”

This initial reception could not have been encouraging to Williams. But, not long after this, she was with the same friend at a roundtable performance event. The friend, to Williams’s surprise, suggested that she perform “Boy,” as it seemed to fit the occasion. “And she was kind of making a face like ‘Not that I like it…’” Williams sang the number to quiet but sustained applause. After the show, a number of people told her that the song had spoken deeply to them. She realized, then, that she had hit on something important.

In the years following the release of The Honesty Room, the song would become a favorite not only with fans of folk music, but also within New York City’s cabaret community. It has been performed by such singers as Julie Reyburn, Lauren Stanford, Mary Sue Daniels, Nancy Stearns, Helane Blumfield, and Dawn Derow. (If you’ve sung it and were not included in this list, please let us know—and maybe tell us something about your experience with the song.)

Every time I’ve heard “Boy” sung, I’ve been struck by how expertly crafted it is, and by what sterling opportunities for dramatic interpretation it presents. The song treats the notion of gender fluidity—which spooks a lot of people—as something rather ordinary, as something to be not feared but embraced.

“I’m Not Breaking Any Law”

“Boy” has a pleasing, rollicking melody that suggests childhood gamboling about in search of adventure and innocuous mischief. It begins with a description of a childhood game of “let’s pretend” in which the narrator fibs to Peter Pan, telling him that she is a boy, in order to run with him and his cohorts. “I’m glad he didn’t check,” she says, rather cheekily. She then tells briefly of the adventures she had with Peter and his gang.

But soon—and not for the last time—we learn something about the adult narrator who’s doing the looking back. She recalls leaving a late-night gathering and being told she needs to have someone accompany her back to her place. “You can walk me home,” she concedes at the end of the song’s first section, “but I was a boy too.”

The second section of the song follows the past-and-then-present pattern that’s been established. Looking back once more, she describes playing topless as a young kid, riding her bicycle near her home. A neighbor tells her to put on a shirt. She is defiant, but she also acknowledges that such days of freedom are coming to an end as puberty encroaches. “It’s the last time. I’m not breaking any law,” she tells the neighbor. Then the song returns again to the singer as adult. We find her in a store with a sign encouraging her to wear clothes that show a lot of skin and accentuated curves. “That can’t help me climb a tree ten seconds flat,” she grouses. She realizes that the corporate world feels it must capitalize on sexual differentiation and sexuality to make a buck. But her own history tells her something different, something truer.

In the song’s third and last section, the narrator talks of how she has kept her past life as a boy under cover. However, she goes on to describe a scene between herself and “the man I’m with,” in which she comes clean about her previous boy’s life. (Note that “the man I’m with” could mean a romantic interest, a platonic friend, or simply a man with whom she happens to have been conversing at the moment.) This is the point at which she issues the “you win” statement. The song’s O. Henry-like reversal—in which the man reveals that he was once “a girl”—comes as a swift outpouring and ends the song. Williams doesn’t give the narrator a chance to respond to the man’s confession. She leaves that to those who have heard the song.

Time Traveling

Two-time Bistro Awards honoree Julie Reyburn has been performing “When I Was a Boy” since before she was officially a cabaret singer. She learned of Dar Williams when she attended a Sally Mayes show at Eighty Eight’s in 1999. Mayes had sung “The Babysitter’s Here,” another story-song by Williams.

Instantly, Reyburn became a Williams fan. She went to see her in concert, and eventually the two became acquainted (through a mutual friend, the late Michael Nelsen). “Before I made my cabaret debut in 2000, I was playing small clubs, just me and my guitar. ‘The Babysitter’s Here’ and ‘When I Was a Boy’ were always in my set. By the time I was putting my debut cabaret together, I knew I had to have a Dar tune in it. ‘Boy’ made the cut.”

She feels that simplicity is one of the key ingredients in the song’s effectiveness. “The lyrics take center stage. There is a melody, but [for] a singer, what is most important is the connection to the story.” On occasion, she has performed the song almost as “speak-singing.” And, she says, “Boy” worked just fine with that approach.

She was drawn to the yearning for simpler times that the song encompasses—what she calls its “time-travel aspect.” During her own childhood, she indulged in some of the same rough-and-tumble “masculine” activities alluded to in the song: climbing trees, playing at being pirates. “The real punch emotionally in the song is when we are confronted with the reality that in adulthood we forget how to play, how to cry, how to feel. We buy into societal norms about gender identity. Or we don’t.”

Her debut show, Fate is Kind (at Judy’s Chelsea in 2000), dealt with coming of age and accessing one’s inner child. Reyburn decided to continue singing “Boy” while accompanying herself on the guitar. “It was a nice diversion in the show to all of a sudden have me play guitar and tell a story. My music director [Mark Janas] and I have also performed the song on piano, which packs the same emotional punch, but there is something about me and the guitar.” When she went to perform the song for her CD (also called Fate is Kind), she played and sang the number in a single take. (You can purchase the track from Amazon here.)

“One of the biggest thrills for me,” Reyburn adds, “was handing the Fate is Kind CD to Dar and thanking her for inspiring all us singers. I was over the moon when she loved my version. I was pinching myself.”

Not the Singer But the Song

Mary Sue Daniels found “Boy” when she was in a class taught by singer-director Lina Koutrakos and musical director Rick Jensen. Daniels had in mind a show about her own early years in Montana. The show that eventually materialized was called Straight Outta ’Conda (performed at Don’t Tell Mama). The engagement led to her receiving the Ira Eaker Special Achievement Award at the 2018 Bistro Awards.

In a meeting with Jensen, Daniels had suggested a few different song possibilities, but he was not enthusiastic about any of them. He then played Dar Williams’ recording of “Boy” for her on his computer. “I immediately knew that this was my song,” she recalls. She had planned spoken narration that she thought would work perfectly with “Boy.” Jensen told her to work on this story/song sequence and bring it to the following Saturday class with Koutrakos.

“I brought it in, and went in front of the class, and said. ‘I want to do a show about my childhood.’ And Lina rolled her eyes and said, ‘OK. Whataya got?’ So, I told the story and…I sang, and she said, ‘OK. If that’s what your show is gonna be like, then I’m in. I want to see more of that.’” (Koutrakos would direct Straight Outta ‘Conda, with Jensen as musical director.)

Daniels considers herself primarily a storyteller, and she finds that the song’s narrative-driven nature suits her style. “It pulls the audience in. They have to pay attention, because—all of a sudden—something will drop, and it’s like, ‘What? What did she just say? She says she was a boy on her bike?’ It was great watching people perk up like that.” Here she is at Don’t Tell Mama in 2018 singing “When I Was a Boy” from her show Straight Outta ‘Conda:

She has always been less secure about her abilities as a vocalist than about her acting and storytelling skills, and this song’s melody was “intricate and range-y.” She has learned to focus on the lyrics and trust that she has the notes at her command. Returning to the song recently and working on it in a new class, she delivered it “more spoke-sung but on pitch.”

“And the parts where it goes a little higher—they felt more ‘lofted up’ than forced…. I think that, taking that pressure off myself, I sing it better—when I’m not thinking about the vocal parts so much. I’m just trusting that my voice will go where I lead it.”

Join Mary Sue Daniels, telling her “When I Was a Boy” story as we sit across the table from her:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1P8yamc9jyDdzPWUpnYU2ZZiEH_zllG0r/view

After her success with Straight Outta ’Conda in Manhattan, she took the show back to ’Conda (Anaconda, MT) to perform it for friends and family. The stories and songs in the set worked together so seamlessly that some people thought Daniels had written all the music herself, including numbers actually composed by Leonard Bernstein, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell. When she sang “Boy,” she observed the same “perking up” phenomenon in Montana that she’d experienced at Don’t Tell Mama.

“The song always, without fail, feels dynamic in that way—in the audience engagement. It’s them being involved in the song, not in the performance of the song. You know what I mean? It’s not necessarily their being aware of what I’m doing. It’s what the story is telling them. And that’s what I love about the song.”

One More Time

As good as “When I Was a Boy” is, I wondered whether it might lose some of its charm after repeated listenings, once the surprise elements (particularly that dramatic reversal involving the confession of the protagonist’s male companion) have become not so surprising. Could the very popularity of the song somehow dilute its power?

Reyburn and Daniels both say no.

“I’ve been singing this song since 1999 and I’m not sick of it,” says Reyburn. “I can’t imagine an audience getting sick of it. Each singer who performs it has to bring themselves to it or it won’t work. I look forward to hearing other versions.”

Daniels also believes the song “stands up to repeated tellings.” She feels that the surprise ending involving the male companion is only one aspect of the song’s strength. She does, however, wonder whether “Boy” will continue to have as much relevance to younger audiences, for whom expectations regarding gender conformity and nonconformity have not been so rigid. The song might seem “trite,” she says, to someone who identifies as transgender.

Or not. There have already been some unexpected renditions of “Boy,” including by singers who identify as male. Self-proclaimed British “Cabaret Geek” Paulus (who performs both in and out of drag), for instance, has included the song in his shows:

As for Daniels, she sees some universal components in the piece:

“[The song] is evocative of a time when options were limitless—and then sitting there and thinking, ‘Wow, look how limited I am at the moment. I’m feeling this horrible constriction.’… [The character] shares this secret, and it brings her back to this happier time. And, in sharing, she learns something. And so—you know—that’s lovely too.”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.

Great piece on one of my favorite songs, Mark. I was thrown by the title of the piece, because I don’t think of the point of the song being gender fluidity so much as it’s about the rigidity of gender roles in society, but reading this makes me realize (even more than usual) how those two concepts themselves overlap (maybe gender issue fluidity?) And your stories about the song are themselves revealing about the way people perceive becoming an adult in this society. Personally, I always cry at the end of this song, as I do at the end of any song that reveals the depth of the heart aching created by essential human needs thwarted/deprived–in this song, it’s the realization that when we are forced into societal roles, we all lose, even the ostensible winners.

Thank you.

Belated thanks for your kind comments, Shellen. What strikes me most about “When I Was a Boy” is that it can prompt the same deep emotional response, time after time.