Cabaret Setlist: “It Never Was You” — Music by Kurt Weill, lyrics by Maxwell Anderson

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Song #5 in this running series

Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson’s “It Never Was You” might be better known today were it not for Walter Huston.

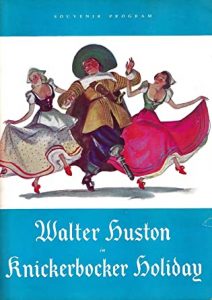

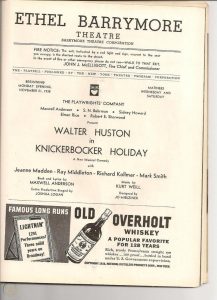

The 54-year-old actor was slated to appear in Knickerbocker Holiday, a 1938 Broadway musical based on Washington Irving’s A History of New York by Diedrich Knickerbocker. This was a satirical work, set in 17th century New Netherland. Huston, who would go on to win an Academy Award for Treasure of the Sierra Madre, was engaged late in the casting process to play the show’s antagonist, Pieter Stuyvesant.

According to Anderson’s biographer, Alfred S. Shivers, Huston felt that his character should have more to do musically. He prevailed upon director Joshua Logan to have Anderson and Weill create a new number for Stuyvesant to sing to the ingenue, Tina Tienhover, for whom the character had romantic feelings. The result was “September Song,” a ballad that captured the attention of music lovers beyond Broadway when it was recorded not only by Huston but also by Bing Crosby and, later, Frank Sinatra.

“Members of the production cast were certain that the love duet ‘It Never Was You’ would prove popular,” writes Shivers. “But they were all surprised when ‘September Song,’ as crooned by the irresistible Huston, became the favorite.”

When Knickerbocker Holiday became a movie in 1944, “September Song” was its musical centerpiece. “It Never Was You,” on the other hand, was not sung in the film, although its melody can be heard in the background in the same dramatic sequence in which it had been sung onstage.

“September Song” is still, certainly, the more widely known of the two songs. But in New York’s cabaret community these days, the tide may have turned. I’ve heard “It Never Was You” sung regularly in Manhattan clubs over the past decade. “September Song”? Frankly, I can’t recall a single instance.

Knickerbocker’s story centers on a love triangle among the power-corrupted Stuyvesant, young Tina (Jeanne Madden), and her more age-concordant suitor, Brom Broeck (Richard Kollmar, most famous, perhaps, as husband of columnist Dorothy Kilgallen). In the show, the song is performed by a pair of lovers who have sown wild oats during a separation from one another, although both yearn for a return to their deeper mutual affection. Brom and Tina have “tried a kiss here and tried a kiss there.” But those were meaningless flirtations.

While there was no cast recording made of the 1938 show, a 2011 recording of the score for a Collegiate Chorale concert—featuring Ben Davis and Kelli O’Hara—gives us an idea of how the number was originally presented: Listen here.

Note the song’s leisurely paced verses, which are essential to the integrity of the song. There are some verses from musical-theatre songs that are seldom heard outside of the context of the theatre, perhaps because their lyrics refer so explicitly to circumstances in the show’s libretto. Other than in a production of My Fair Lady itself, for instance, how often do singers perform the verse to “On the Street Where You Live”? It’s easy to forget there even is one. That’s far from the case with “It Never Was You.” Singing its refrain alone would make little sense. That refrain, by the way, is also unusual—containing a lovely, long, sprawling bridge, beginning with the lyric “An occasional sunset reminded me….”

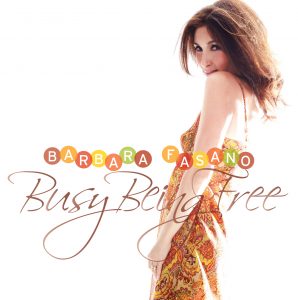

Barbara Fasano, a Bistro Award recipient who recorded “It Never Was You” for her 2015 CD Busy Being Free, has a special fondness for the song’s verse section: “It’s a bit like [Hoagy Carmichael and Mitchell Parish’s] ‘Stardust,’ where the verse is such a rich meal unto itself. The verse is essential to me, and the most beautiful part of the song.”

As the Collegiate Chorale recording reminds us, there are actually two verses in the song, one for each of the lovers. The first verse makes some reference to the Knickerbocker storyline, as Brom Broeck sings of “a certain father’s daughter,” referring specifically to Tina Tienhover. At some point after the show’s opening, Anderson seems to have created some less libretto-driven lyrics for this “male” verse.

According to Natalie Douglas, who included the song on her CD The Human Heart (honored in 2017 with a Bistro Award), vocalists who performed and recorded the song in decades past tended to perform whichever verse matched their respective gender. In recent years, though, that has changed, with artists mixing and matching couplets and quatrains. Douglas, for instance, sings the “male” lyrics. She avoided Tina’s couplet “For when you’re out in company, / The boys and girls will pair,” because it seemed both too quaint and too “hetero-centric.”

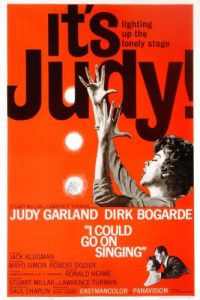

“It Never Was You” finally made it into a motion picture in 1963, when Judy Garland performed it in what turned out to be the final film of her career: I Could Go on Singing. This was an influential rendition of the song—some would argue the definitive one. And it’s hard to disagree with that notion. To me, the hushed, emotion-charged voice of Garland (accompanied only by Dave Lee on piano until the orchestra chimes in at the very end) suggests that the song was, perhaps, too sophisticated, too knowing, to have been wasted on the rather callow characters of Tina and Brom. Hear for yourself Garland’s rendition.

Anderson, best known in his era for writing verse drama, had imbued the song both with a colloquial, easy-going quality and a mysteriousness born of his nuanced wordplay. Take the line “It never was anywhere you.” The word “anywhere” serves to give the lyric two different meanings: “Those other romances of mine never came anywhere close to what I had with you” and “I could never seem to find you anywhere.”

Then there’s that powerful explosion of aural imagery: “a heartbreak call from the meadowlark’s nest.” Pondering the significance of that phrase can keep a listener up wondering all night.

Fasano refers to Anderson’s lyric as “a full palette of color” and “achingly gorgeous.” But she also credits Weill’s melody for much of the song’s appeal: “Interestingly, this is a song I often hum when I’m walking down the city streets. There is something exquisite in the melody and its intervals. Making all that sound smooth while hopping down Broadway is an excellent vocalise!”

She came to know the song through a recording by Teresa Stratas (click to listen). She began performing it as homage to Weill when singing in concert series at Manhattan’s Neue Galerie, which honors German and Austrian art.

“When I record, I work with jazz musicians, and jazz musicians revere Kurt Weill for his soul and harmonic originality. When I presented ‘It Never Was You’ to pianist/arranger John Di Martino, he jumped at the idea…. I’d wanted to record it for years, and I was thrilled John agreed it should go on the album.”

She and Di Martino took several takes to find just the right tempo for the song, but the version that wound up on the album is relatively straightforward and frills-free. “Most of the songs on Busy Being Free have instrumental solos, but ‘It Never Was You’ does not. It begins with just piano and voice and then the trio enters on the chorus. And I sing only one chorus. That’s it. John plays around with the harmonics and I sing the melody pretty much as written—not much substitution. At the end, I deliver the vocal as written…and John plays alternate chords underneath.” Listen here.

Douglas heard the song as a child, when her mother would play recordings of it—although she doesn’t recall whom she first heard perform it. She became familiar with the Garland version early on and believes it may have prompted her idea that the song was “confessional,” that it came from the voice of a woman who has experienced a great deal of life:

“It was so perfectly evocative of an emotional connection, but also of a time and place. It felt…atmospheric without being overly descriptive.”

Keeping in mind, perhaps, the lines “Yes, I looked everywhere you can look without wings, / And I found a great variety of interesting things,“ Douglas explains: “There are some songs that set the scene in a very literal way. And this [song] doesn’t. But I still get a sense of place and…adventure: the idea of searching and traveling, and of bigger, wider worlds.”

She first performed the song in 2008, as part of a show celebrating the 70th anniversary of Café Society, Manhattan’s groundbreaking integrated nightclub, which was managed by Barney Josephson. Though she is not certain the song was ever sung in Josephson’s club, its strains were certainly being heard in New York when his venue opened, and she thinks that Weill, who had fled Nazi Germany and held progressive views, “might have wanted his songs sung in that room.”

Douglas’s “Café Society” version of the song had a slightly different sound than the one that wound up on The Human Heart. Mark Hartman wrote the arrangement for the CD, with Brian J. Nash arranging the cello part. Also, Douglas sang a slightly different melodic line at the end of the song than she did in 2008.

When Douglas celebrated the release of The Human Heart at NYC’s Birdland, she, Hartman (on piano), and Nash (on keyboards) were joined by Jim Cammack (bass), Kiku Enomoto (violin), Patience Higgins (reeds), and Charles Ruggiero (drums). Here’s the version of “It Never Was You” from that 2016 show: Watch/listen.

Douglas urges singers who are interested in singing this song—or any song with a history as rich as this one’s—to don their researcher’s hats. It’s helpful to know the historical circumstances behind a song, she says, “before you impose your own set of circumstances on it.”

Her investigations unearthed the fact that Anderson wrote Knickerbocker Holiday as a satirical allegory on the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whom the playwright saw as a power-thirsty figure whose policies during the Great Depression amounted to a dangerous overreach by the executive branch. On the other hand, she says, Weill had experienced “real fascism” in Germany and was receptive to FDR’s New Deal policies. She wonders if any of this political background created a tension between the collaborators that somehow influenced their art—including the making of this love ballad. This line of questioning may seem farfetched—a reach—but when you’re solving the riddle of what makes a song do what a song does, you may want to keep reaching to all available corners.

In any case, Douglas and Fasano agree that “It Never Was You” is a crowd pleaser. Douglas says that it was partly the enthusiastic reception the number received in 2008 that convinced her to include it on the album. Adds Fasano: “When I perform ‘It Never Was You’ on a very good night, often there’s a hush before the applause. I think the song can cast a spell.”

In closing, here are a couple additional performances that my guests for this column recommended:

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.

Mark, last year in my show “And Kurt Weill Begat Kande and Ebb”, Matthew Martin Ward sang “September Song” and we duetted on “It Never Was You”.

Thank you, Sally, for jogging my memory. Of course. You and Matthew Martin Ward presented a loving and thoughtful tribute to Weill and to that whole tradition. Apologies, and thanks–both of you–for so many evenings of musical reflection and wit. Miss them and you.

I had the thrill of having Judy Garland sing this song right into my ear. We were dancing, and she was humming along to her own version

coming from the loudspeakers. See my memoir, Heartbreaker, p. 58-59.

Now that’s what I call stereophonic sound! Thanks for sharing this story.