Six Authors Talk About Publishing Books on the Great American Songbook and Its Artists in Today’s Market

So, you want to publish a book about your favorite composers or singers right out of the Great American Songbook? Or, iconic Broadway musicals, for that matter?

Think again, assert authors I interviewed, all of whom boast impressive track records. It’s more challenging than ever, they agree.

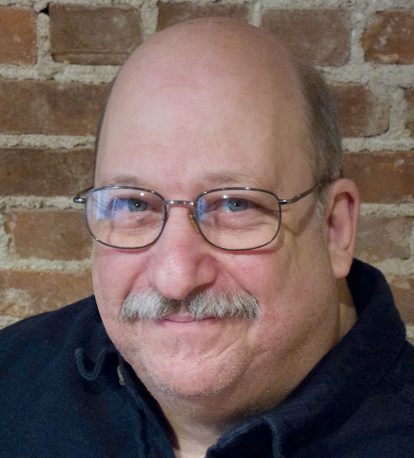

“Big publishers like Knopf or Simon & Schuster won’t publish these types of books at all,” says Ken Bloom, a Grammy Award-winning theatre historian, playwright, record producer and, most central, a prolific author. “Smaller publishers won’t give you an advance.”

He’s in a position to make the comparison. His roster of books include, among many others: American Song: The Complete Musical Theatre Companion; The American Songbook: The Singers, the Songwriters and the Songs; the best seller, which he co-wrote, Broadway Musicals: The 101 Greatest Shows of All Time; and, most recently, The Complete Lyrics of Sheldon Harnick.

The academic press, while prestigious, has always offered modest advances, he says though this time around he didn’t care because Harnick (Fiddler on the Roof, She Loves Me, and The Apple Tree) paid him to write the book. Still, given the scope of the book, not to mention the legendary status of its subject, he was floored that he was unable to land a major commercial publisher willing to offer a serious advance.

“It is an enormous book listing more than 2,000 songs,” says Bloom. “But, more important, it includes Sheldon’s commentary and his recollections about every song. And each song is supplemented with excerpts from other sources and experts who talk about the songs.”Other notable authors such as Will Friedwald, Geoffrey Mark, and James Gavin echo, to varying degrees, Bloom’s experiences. Gavin is a Grammy nominee and a recipient of two ASCAP Deems Taylor/Virgil Thomson Awards for excellence in music journalism. He is the author of such critically acclaimed works as Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne; Intimate Nights: The Golden Age of New York Cabaret; Is That All There Is? The Strange Life of Peggy Lee; and George Michael: A Life, the latter published by Abrams.

“I started shopping my last book around in 2017 and it wasn’t published until 2022,” he recalls. And Abrams was the only one who was interested. Everyone else said no. And George Michael is a relatively recent pop icon.”

“In the end, the book got a tremendous amount of attention, including reviews in the New York Times Book Review, the Los Angeles Times, People, USA Today, and Spin; three items in the New York Post; a two-page spread in the Daily Mail, and features from CNN.com, Interview, Today.com, and more additional international coverage than I can list here,” he continues.

Arguably, the publishing landscape started shifting as much as 30 years ago, but COVID was the turning point all agree. Book publication, especially for niche works, plummeted across the board, short of sure-fire hits such as gossipy biographies of say Frank Sinatra or Ella Fitzgerald. More than ever, I was told repeatedly, the publishers are seeking those high-profile name books to compensate for their four years of losses during the pandemic.

“And authors of these books demand increasingly large advances, leaving fewer and fewer resources for smaller prestige works,” explains Will Friedwald, music critic and author of 10 books including the award-winning A Biographical Guide to The Great Jazz and Pop Singers; Sinatra! The Song Is You: A Singer’s Art; Stardust Melodies: The Biography of Twelve of America’s Most Popular Songs: and The Good Life (written with Tony Bennett). He is the 2024 winner of the Jazz Journalists Association Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in Jazz Journalism, contributing to such publications as the Wall Street Journal, the New York Sun, Vanity Fair, and Playboy, among others. He has written over 600 liner notes.

His spectrum of writing credits helps, he admits, “but the subject is more important than the author, unless you’re Stephen King. If I wanted to do a book on Taylor Swift, I probably could sell it. Blossom Dearie, not so much.”

“The whole book industry has changed,” adds Bloom. “The traditional business model published a wide range of works. The profits made from best sellers paid for everything else. That’s no longer the case. And after COVID, libraries, which used to purchase our books, were the major marketplace for our books, no longer had the money to buy them either.”

There are other shifts that also limit the possibilities for publication and make the entire experience almost cold and impersonal, says Geoffrey Mark, a show business historian whose books include Ethel Merman: The Biggest Star on Broadway and Ella: a Biography of the Legendary Ella Fitzgerald.

“At one time, editors were personally committed to books and authors,” he says. “Now editors get book proposals and then the editors are competing with each other for which books will get published. In the end, book selection is done by committee. You no longer have an editor loving a book and holding the author’s hand throughout the process. You rarely have book publishers throwing parties for books when they come out. They don’t pay for press junkets or travel expenses either The major cost a publisher has is shipping the books to Barnes & Nobel. It’s amazing anything gets published unless there is a TV or film tie-in.”

The larger conundrum is the loss of audiences for these books, say at least some of our authors.

“Readers who might be interested in Harnick, for example, are either dead or of advanced age and no longer buying books,” says Bloom. “I have one exception, Charles Kirsch, a 12-year-old, who loves the old music and is eager to learn everything about it. But generally young people are just not interested in musicals that were popular before their time. For them it’s the songs of Wicked or Phantom, assuming they’ve even seen those shows given the exorbitant cost of tickets.”

Lack of support and exposure is a major contributor, everyone says. While at one time, musical numbers right out of Broadway shows and the Great American Songbook could be heard on the radio and a host of TV variety shows, that’s no longer the case. The songs and music of yesteryear are not part of contemporary pop-culture.

The loss of vinyl records with liner notes doesn’t help. Admittedly, vinyl records are enjoying a comeback, but these generally don’t include the old Broadway musicals or American Songbook numbers.

Back in the day the media routinely covered the cabaret scene, says Gavin. “The New York Times had Stephen Holden, The New York Post had Chip Deffaa, on the radio we could hear Jonathan Schwartz who was a tastemaker. Their presence made an impact on attendance. There was never a huge audience for cabaret but it was still covered.

“I grew up in a time when smaller artistic endeavors were allowed to flower,” he continues. “The pandemic sped up its demise. Many people who might have gone to theatre or cabaret before began to feel they could get the entertainment they wanted at home. They also had less money to spend on shows, and probably on books.”

A Dissenting Voice

Not everyone sees gloom and doom, or that it’s worse today than it ever was.

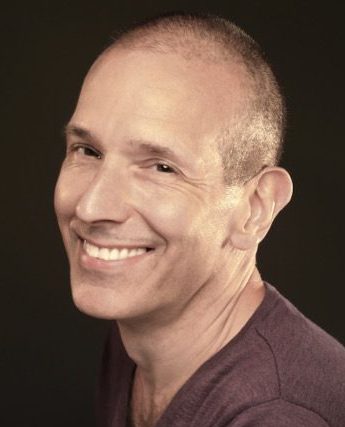

“For writers, the need to persuade publishers that what they were doing is worth the investment of time, money, and other resources is a constant,” emphasizes David Hajdu, book author, music critic, songwriter, cultural historian, and professor at Columbia’s School of Journalism. “I follow Publishers Weekly and I follow the marketplace. And it seems that a healthy number of books on music of all kinds are being published—books about mainstream pop, books about country music, books about rock bands, and books about R&B. There are endless books on the Beatles. I have four shelves of books on the Beatles.”

Books that speak to the interests of cabaretgoers are not in short supply either, he continues.

“A new book about Randy Newman [A Few Words in Defense of Our Country: The Biography of Randy Newman by Robert Hilburn] is first-rate,” he says. “It shows how he has moved forward the Tin Pan Alley tradition. A book on Ira Gershwin is coming out soon and so is a book on Broadway cast albums. If you have a story to tell that’s worth telling, that has resonance and offers new insights, you will find a publisher.”

The author of such books as Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn and Love for Sale: Pop Music in America, Hajdu says he wanted to write a book about Lena Horne. He was conversant in the topic having read the six Horne biographies. And to top it all off, he had personally known Horne and had an archive of recorded interviews with her that had never been used.

“But in the end I decided I don’t have enough to say to justify a seventh book.” he recalls. “It’s not that a great performer or composer of 1940 is of no interest, but 80 years later there may not be anything new to say. And that becomes increasingly more difficult as time recedes.”

He debunks the myth that young people are not interested in stars of the distant past like Irving Berlin. But he points out that the interests of the 20-, 30-, or 40-year-old crowd are no more intellectually limited than that of baby boomers (his generation) when they came of age.

Yes, he and his cronies were exposed to performers like Ella Fitzgerald and Bing Crosby crooning the oldies on The Ed Sullivan Show and other variety programs. And it is true, he concedes, that there is nothing analogous today.

But through an array of online platforms, kids are exposed to the past. The past for them is the ’70s when hip-hop was king. “We tend to forget how far back hip-hop goes,” Hadju says. “It has its roots 50 years ago.”

He insists niche books are alive and well and that there is a market for them if you come up with something original. His next book, for example, The Uncanny Muse, explores how machines, automation, have informed music over time and considers one of the most controversial facets of AI: artificial creativity.

He emphasizes there is a real marketplace for books about “those who have been traditionally overlooked. Two books on women writing music and musicals will be coming out shortly,” he says.

Asked how he feels about self-publishing, he says he has no philosophical objection to it though he is wary of the pervasive “sloppiness” in many of these books that have no editors or fact-checkers, or even anyone to make sure that indexes and footnotes are accurate. In fact, he still hires his own fact-checker before handing in his manuscript to a commercial publisher. And errors escape detection nonetheless.

“The lack of fact-checking is a major problem,” Hajdu says. “We live in an age of the web. Misinformation and disinformation is rampant. It has become normalized.”

Self-Publishing, Anyone?

No one disputes that self-publishing may be an option to the rejections, disappointments, and frustrations that come with attempting to land a commercial publisher. If nothing else, it gives the author a “published book” on his or her resumé. For some this is important.

A few such books do manage to break out. But sales are usually modest at best and the chances of getting reviewed by any major venue is virtually non-existent.

With one notable exception, none of those I spoke with have gone the self-publishing route. They uniformly find the prospect too much work, too much expense, in short, just too demeaning for negligible results.

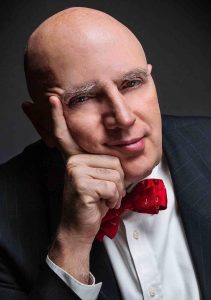

By contrast, Will Anderson doesn’t see it that way at all. For him it’s the preferred choice. He and his identical twin brother, Peter, form the renowned duo who are arrangers, composers, and most notably jazz saxophonists and clarinetists. [Editor’s Note: 2018 Bistro Award honorees for Outstanding Instrumentalists.] They have performed at Carnegie Hall, the Blue Note, and Jazz at Lincoln Center, among other major venues.

Anderson believes that his audience craves more information, and for that reason he decided to write a book, Songbook Summit: 15 Pioneers of American Sound, describing and analyzing the works of such icons as The Dorsey Brothers, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Irving Berlin. It came out in August and he never even considered seeking a commercial publisher.

“Self-publishing allowed me to be in complete control of the book,” he recalls. “I did my own editing and the photos I used were available in the Public Domain, though I hired a graphic designer. The book is 124 pages with 16 photographs. I printed 1,000 copies. The total cost was $8,000. It is available on Amazon for $20 and we promote it on Facebook and through our emailing list that includes more than 1,000 friends and fans.

“But I wrote the book specifically to sell with our CDs at our performances. Our audiences love to have information behind the music they’ve just heard. The book enhances their experience after they’ve seen us perform or are listening to our CDs at home. I sign each book I sell and it becomes a personal memento, my connection with our audience. I did not expect big sales or reviews. I did not pursue reviews, although we were reviewed by the Syncopated Times and the New Jersey Jazz Society.”

Anderson stresses that his experiences are not necessarily representative. The cost to self-publish can range with the number of books an author is printing, assuming the writer is going to print hard copies at all.

“You can also print your books on demand,” Anderson says. “Printing on demand is certainly less costly than printing 1,000 copies up front. You may also post a pdf of your book online and just give it away.”

Anderson’s book is available on Amazon, which prints a book exactly the way it comes in. For Anderson that was a virtue. Others hire pros to edit, track down photos in the Public Domain, and promote the book. Some publishers include those services in their contract and yes, that too, is taken into account in the final bill.

Anderson says he would have no hesitation about self-publishing again.

Are You Up for Endless Self-Promotion?

What all the authors I interviewed share in common is the realization that self-promotion is largely in their court, whether or not they have a commercial publisher. What one does or doesn’t do, of course, largely depends on goals and temperament.

Hadju does little marketing and promotion. “I don’t care about it,” he says. “Yes, I will do events, but I leave before the reception.”

Friedwald states his feelings bluntly: “You do anything you can, lately that’s the dreaded social media, which I despise with the burning intensity of a thousand suns. But you do anything and everything you can think of.”

By contrast, both Gavin and Mark are adamant about the need for self-promotion and willingness to take on the burden themselves. With his Ella Mark hired his own publicist, Harlan Boll, who helped him arrange for the approximately 300 radio, TV, and podcast interviews he did. He also doled out close to $10,000 for his own travel, hotel, and food expenses.

Gavin staged musical events across the country and beyond to celebrate and promote his book, Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne.

“I was the narrator,” he recalls. “I created a concert with a jazz trio and projected stills and video that toured on and off from 2010 until 2017. Its star for most of that time was Mary Wilson of the Supremes. It proved an effective way to promote my book for years after its publication and to commemorate Lena.

“As for ‘upping my game,’ I suppose I could be more aggressive on social media, although I’m pretty good. I don’t know what stone I’ve left unturned, and I work with some excellent publicists. I’m always looking for creative ways to promote my books in an age when print media have largely died off.”

###

About the Author

Simi Horwitz is an award-winning feature writer/film reviewer who has been honored by The Newswomen’s Club of New York, The Los Angeles Press Club, The Society for Feature Journalism, the American Jewish Press Association, and the New York Press Club (among others). She received an Honorable Mention from Folio: Eddie and Ozzie Awards for her two drag stories (May 22, 2020, August 4, 2020) published here on BistroAwards.com. More recently, she was the recipient of the 2023 New York Press Club Award and won three 2023 L.A. Press Club Awards., including first prize for film criticism (for reviews published in the Forward). The publications that have printed her work include The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Hollywood Reporter, Film Journal International, and American Theatre. She was an on-staff feature writer at Backstage for fifteen years (1997-2012).