The Evolving Genre/Gender-Bending Art Form Known as Drag is One Big Hybrid

(This is Part One of a multi-part series on alternative cabaret by Simi Horwitz.)

The diva-inspired bitchy and/or adorably naughty drag queen is still with us. Hey, she’s the archetype and a few have elevated drag to high art. Think Varla Jean Merman, the self-described love child of Ernest Borgnine and Ethel Merman, indisputably brilliant and in a league by herself.

Still, a new crop of drag artists (some campy, some not so campy) have hit the scene appearing in upscale cabarets, downtown dives, theatre venues and TV’s RuPaul’s Drag Race. Now they’re taking it to digital platforms, thanks to COVID-19. And what a complex, multi-layered lot they are, reflecting an array of social-cultural-political trends and expanding theatrical aesthetics.

Cabaret performer Sidney Myer (who also serves as the booker at New York’s canonized Don’t Tell Mama) says the singular difference between drag artists today and yesteryear is that the line between their on and off stage personas is growing increasingly thin. Life informs art and art informs life and everyone is in on it.

Intimate and confessional revelations are not uncommon now. They make for good theatre and offer life lessons. Latrice Royale, best known for her over-the-top appearances on Drag Race, talks about her drug abuse, her stint in prison as a gay man, and the loss of her mother while serving time. She can grow teary-eyed and emotional.

“I pride myself on telling my story openly,” she says. “I want to show that no matter what hardships you face, you can move on. ‘Get up, look sickening, and make them eat it.’ That’s my mantra.” She also revels in (to quote her) her “chunky and funky” side, “embracing all of my curves and swerves,” she adds. “I’ve become a role model for body positivity and the plus-size community.”

Drag by its very nature —an exaggerated version of itself and political to its core —is the perfect vehicle for pushing issues that are “near and dear” to her, she says. Latrice (aka Timothy Wilcots) is a self-acknowledged drag queen with all its celebratory excess in tow.

Benjamin Putnam, another Drag Race alum, also rejoices in his (or “her”) stage persona, BenDeLaCreme, a mid-century diva with a smidgen of the vaudevillian, burlesque star, and cartoon caricature thrown in for good measure.

“She’s not unlike a Muppet,” DeLa says. (Most people call him DeLa). “Her sexuality is suspended and she’s separate from me.” But make no mistake, Putnam is present onstage too with his wink-wink, nudge-nudge signals to the audience.

Hybridity is the password. Consider alt-cabaret performer Jack Bartholet known to sport a tutu onstage and his face adorned with sequins and painted designs, yet refuses to define his performance as drag. “It’s pseudo-drag,” he insists.

Real drag is time-consuming and labor intensive, he explains. Adjusting wig, costume, nails, applying makeup and donning heels is heavy preparation, whereas his “drag” application is almost casual. He dons makeup and outfits on stage. Social commentary is at play but so is the sight gag.

“My show speaks to my otherness, my queerness, but when I put on a tutu and eye-liner, I don’t become a woman and I’m not a man in drag either,” he says. “I use queer showmanship to tell my story. I poke fun at myself as I honor the young boy I was who loved dress-up. And here I am still doing it as a 30-year-old man. I’m living as a proud gay man out loud. I still love sparkles.”

Onstage he’s a heightened, theatricalized version of himself, interlacing stories of his life, with songs and, on occasion, tackling hot button issues (from gun control to toxic masculinity) while employing cheeky, queer charm to seduce his audiences, softening them up to hear the harder truths. Jack Bartholet at the 2020 Bistro Awards.

And then there’s Daniel Alexander Jones’s onstage persona, Jomama Jones, an American-born entertainer (in the Diana Ross tradition) who fled the country during the Reagan years, living as an exile abroad until she made an American comeback in 2010. She is regal, charming, and ingratiating, greeting members of her audience as if they were visitors to her home.

“She is not a man in drag, which sometimes disappoints audiences who may want the campy, insulting queen,” says Jones. “Jomama is a cisgender woman and when she’s on stage, I, Daniel, go away. I make room for her. I channel her. She is my alter-ego, and also altar-ego. She connects me to a sacred part of my life, a place of inquiry and contemplation. She reveals what Daniel is seeking.” Tongue slightly in cheek, he says he has no way of knowing if she’s straight or gay or, even, the origins of her stereotypic-sounding moniker, evoking (depending on viewpoint) mockery, homage or both.

Still, he concedes Jomama was spawned through an African-American-queer lens. It’s no accident that her goal is to bring audiences together (Dr. King is always an informing force); and, similarly, the improvisation that Jomama employs with her audience is deeply rooted in Jones’s dual identity. “For blacks and queers, survival has always demanded improvisation.”

He believes Jomama, like all drag creations, is political, even transgressive in making the viewer think about gender identity in a new way. Perhaps at no time more pointedly than today when “non-binary,” “non-normative,” or “queer” have become the watchwords— replacing (or including) such gender identities as homosexual, bi-sexual, or trans.

“One day I may want to wear a suit and tie,” Jones says. “On another day, I may wear an outfit that’s more feminine. When I’m onstage I’m not playing with gender identities that are separate from me, but rather exploring different aspects of myself. There’s room for the full spectrum of gender identity and sexuality on and off stage. Look at the way we think about pronouns.” Jomama Jones at the 2019 Bistro Awards.

Taylor Mac, a visionary (joyously apocalyptic) drag artist, chooses “judy” as his gender pronoun. (Mac’s “judy” is of course referencing Judy Garland.) On Stephen Colbert’s show he opined, “I choose judy because I wanted a gender pronoun where if anyone rolls their eyes it would immediately make them camp…you can’t say judy without emasculating yourself.”

The great alt-cabaret performer Justin Vivian Bond prefers the title Mx (instead of Ms./Mr.) and the pronoun V or vself (as opposed to him/herself). “I do not believe in the gender binary, and I do not live as a male or female,” V said to me some years ago. “When I played Kiki [an inebriated lounge singer of the duo Kiki and Herb], I was playing a woman. But I was not a man playing a woman, or a woman playing a woman. I was a transgender playing a woman.” (To this viewer Kiki embodied the gay man in drag.) Either way, V now occupies a whole new artistic space onstage as a sophisticated, elegant man-woman singer, a damn good singer.

A lounge-lizard emcee with slicked-down black hair, a shiny baggy suit, and a fake mustache, Murray Hill (one of the better known drag kings), who dubbed himself “the hardest working man in show-biz,” once told me he’s an entertainer who sings, dances, interacts with the audience, and tells jokes. He’s everybody’s favorite uncle at the dinner table after a few drinks. Minus the tuxedo and corny one-liners, he continues as Murray Hill off-stage, but will not say if he’s a trans-man, gay, non-binary, or queer. “I’m something else altogether,” he remarks cryptically.

Ambiguous gender identity is part of a long theatrical tradition. In his Ridiculous!: The Theatrical Life and Times of Charles Ludlam” author and theatre critic David Kaufman cites Ludlam’s performance as Camille in the Alexandre Dumas classic, as an iconic —comic and moving —example of gender blending onstage. He wore gowns but also exposed his chest hair. It was a serious performance, but in drag.

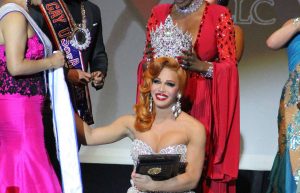

Trans-woman Aurora Sexton is more old-school in her drag performance. During her 20-plus-year career, and rising in the ranks through drag queen pageantry competitions, her onstage world is celebrity-inspired camp. She may bring to life (oversized life) a bevy of fairy-tale villains or impersonate the stars, living and dead —from Lady Gaga to Joan Rivers to Melania Trump, each in her own right resembling (arguably) a man in drag.

Sexton is a new breed performer in her theatrical aesthetic that marries giant puppetry, ventriloquism, and video backdrops featuring characters (played by her) with whom she (in whatever guise[s] she has assumed on stage) interacts flirtatiously, or bitchily, aggressively, or combinations thereof.

But no one is more cutting-edge in her theatrical eclecticism than drag star Sasha Velour, a gender-fluid, multi-media performance artist, heady and hilarious, who hails from a world that is visually and technologically spectacular, while administering an emotional sucker punch in some of her musical renditions.

Equally amalgamated in persona, presentation, and narrative style is Salty Brine (yes that is his real name) playing an inflated version of his gender-fluid self. Depending on the show, he utilizes top hats, facial glitter, fake beards and, in one striking instance, a multi-colored costume, awash in long-flowing feathers. He’s both comic and sinister and at moments suggests the emcee in “Cabaret,” his spin, however, uniquely his.

“I may be in female drag. I may be in male drag. Any role you’re assuming, any costume you’re wearing, is drag,” he says.

It’s a cerebral conceit indeed. In his Living Record Collection shows, for example, he performs all the songs from some pop album (e.g., Led Zeppelin IV, Abbey Road) re-interpreting them within the parameters of a hallowed literary work (from The Odyssey to The Jungle Book to Treasure Island), and interweaving all of it with his own personal narrative. The relationship between the three threads is not readily definable as it’s more closely allied to a stream of consciousness. An orchestra performs alongside him on stage. He dances with abandon.

“It’s a musical, a memoir, an opera, but in the end it’s a play disguised as a cabaret,” he says. “There’s a beginning, middle, and an end and that’s theatre.”

But it’s more than theatre, he adds. It’s a celebration of the queer experience, which speaks to the universal. It’s humanism and raises existential questions. “Who are we and what are we here for?” he asks rhetorically. Salty Brine at the 2018 Bistro Awards.

Perhaps, in varying degrees, guises, sensibilities, all the drag artists are asking the same questions. And how timely is that in a world gone amok?

About the Author

Simi Horwitz is an award-winning feature writer/film reviewer who has been honored by The Newswomen’s Club of New York, The Los Angeles Press Club, The Society for Feature Journalism, the American Jewish Press Association, and the New York Press Club (among others). She received an Honorable Mention from Folio: Eddie and Ozzie Awards for her two drag stories (May 22, 2020, August 4, 2020) published here on BistroAwards.com. More recently, she was the recipient of the 2023 New York Press Club Award and won three 2023 L.A. Press Club Awards., including first prize for film criticism (for reviews published in the Forward). The publications that have printed her work include The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Hollywood Reporter, Film Journal International, and American Theatre. She was an on-staff feature writer at Backstage for fifteen years (1997-2012).