“The Real Ambassadors”: New Book Recalls an Anti-Segregation Jazz Musical Starring Louis Armstrong and Carmen McRae

Say, show tune lovers—did you ever hear of The Real Ambassadors, a musical developed by famed jazz pianist Dave Brubeck (“Take Five”) and his wife, Iola, in the late 1950s and early 1960s? The show was envisioned as a Louis Armstrong vehicle, with Carmen McRae as his love interest. The celebrated “vocalese” trio of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross would also be enlisted to serve as a sort of mini-chorus for the show.

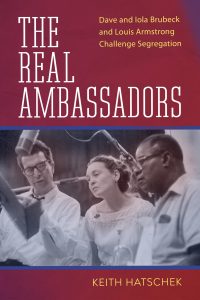

If The Real Ambassadors is new to you, it’s no big surprise. Keith Hatschek didn’t know about the show until he stumbled upon it several years ago and he, literally, wound up writing the book about it—The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Racial Segregation (University Press of Mississippi, 2022).

If The Real Ambassadors is new to you, it’s no big surprise. Keith Hatschek didn’t know about the show until he stumbled upon it several years ago and he, literally, wound up writing the book about it—The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Racial Segregation (University Press of Mississippi, 2022).

After graduation from college, Hatschek had become a working musician, and later a specialist in (and writer about) musical technology and the ins-and-outs of the music business. He’d also became an academic, teaching music business courses. Eventually, he was hired to teach full time at the University of the Pacific, in Stockton, California.

“Part of being a full-time academic is that you’re tasked with doing some research,” he told me in a recent phone interview. But he’d pondered what subjects he might investigate and write about.

Hatschek then discovered that the Brubecks, both of whom were Pacific alums, had provided university scholars with a trove of archival treasures. In 1999, they had donated their papers to their alma mater. Hatschek was delighted upon learning of “this great repository of Dave Brubeck and the history of American popular music, culture and jazz” waiting in the archives, some 200 yards from his office.

Also, at that time, both Brubecks were alive, well, and available to be interviewed.

His first Brubeck-related research project was an article—published in the journal Jazz Perspectives in 2010—about a 1958 tour of Poland by the Dave Brubeck Quartet. While delving into the archival bounty—starting with fan mail that Dave and Iola had collected decades earlier—Hatschek unearthed an article from a Polish jazz publication with a photograph of Dave Brubeck. The photo’s caption mentioned an upcoming musical play, supposedly destined for Broadway, called World Take a Holiday, which Dave and Iola were developing.

This has to be some sort of mistake, Hatschek thought. But when he spoke with the university archivists, they told him, “Oh, the name changed…. There is a musical. It’s called The Real Ambassadors.”

Hatschek was intrigued. Then, he was hooked. And he kept on delving.

Cultural influencers

As young people in California in the 1950s, Dave and Iola Brubeck had both been fervent and vocal in their support for civil rights and desegregation. Iola also boasted a theatrical background, which gave her the confidence to attempt a story treatment and lyrics for a full-scale musical. It was she who instigated the project that would become The Real Ambassadors, though Dave was equally eager to make the musical happen.

The show’s storyline was inspired in large part by an incident involving Dizzy Gillespie. In the mid-1950s, the celebrated jazz trumpeter had helped quell a riot involving anti-American students in Greece. Angry young protesters had been attacking the offices of the U.S. Information Service. But when Gillespie and his band performed, the demonstrators were so taken with their jazz magic that they wound up carrying the bandleader on their shoulders through the streets of Athens. (Iola’s lyric for one of The Real Ambassadors’ songs, “Cultural Exchange,” would focus specifically on Gillespie’s instant success as a “jazz ambassador.”)

“Jazz ambassador” was not a made-up thing. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union found themselves in a competition to convince developing countries to embrace their respective cultural values. The Soviets sent out dancers from the Bolshoi Ballet to represent their national sensibilities, while the U.S. State Department sponsored delegations of jazz musicians to show what Americans had to offer.

But the racial mix in the American jazz scene caused a problem for the State Department. Racial segregation was still entrenched in America, and that sorry fact made it clear to citizens in the countries being wooed that the rosy picture the jazz ambassadors were trying to paint of American democratic principles was somewhat bogus. The whole enterprise began to smell of hypocrisy. After all, Black musicians were central to the music called jazz, yet they were treated as second-class citizens by their government and by their white neighbors. (Soviet propagandists were delighted to point out this contradiction, by the way.)

Serendipitously, while the Brubecks were already at work on The Real Ambassadors, the Brubeck Quartet itself was invited by the State Department to embark on a 1958 overseas tour. Iola and two of the five Brubeck children went along on this trip. Incidentally, the quartet at this time featured a Black bass player, Eugene Wright. In coming years, the Brubeck band would be forced to scrap many performances in the American South, because the combo was racially integrated.

As Hatschek writes in his book: “[Brubeck] argued that the ‘freedom’ he and his fellow musicians enjoyed onstage within the quartet to improvise, listen, and respond to one another equally represented an aspirational model of the same individual rights a good society should afford its people.”

In other words, the collaborative nature of jazz provided a model for the good things democracy might bring to the world—if, that is, Americans could get their act together regarding race.

In any event, when the tour ended, the Brubecks came back to the states even more inspired to make The Real Ambassadors happen.

The political awakening of Louis Armstrong?

The imagined plot line for The Real Ambassadors focused on a fictional Black jazz artist: a bandleader and vocalist/trumpeter known as Pops. Pops is sent by the U.S. government to an African country where he is lauded for his talent. (At one point he’s given the title “King for a Day.”) The acclaim goes to his head, and that interferes with the blossoming romance he is having with the band’s singer, Rhonda.

From the beginning, the Brubecks wanted Louis Armstrong as Pops. But that was a tall order. Armstrong’s career was carefully supervised by a control freak of a manager named Joe Glaser, who was to “Satchmo” what Colonel Parker was to Elvis Presley. (“The Colonel,” however, had not apprenticed with the Al Capone mob in Chicago, as Glaser had done in his youth.) While, at times, Glaser seemed to support Armstrong’s involvement with The Real Ambassadors, he never fully endorsed the endeavor, and he often seemed determined to stall its development. And he had his reasons. If Armstrong’s career were to have taken a detour into a long stint on Broadway, it would have shrunk the income made from those lucrative touring dates booked for the bandleader and his All Stars. And Glaser liked things to stay “lucrative.”

As for Armstrong himself, he seemed eager to perform in the musical, in part because it would let him speak out against segregation in a manner in which he felt comfortable. The show would deal openly with the fact that Black performers who were sent overseas to promote democracy were reined in by Jim Crow laws in their home country. Also, one of the key songs in the show’s score, “They Say I Look Like God,” showed Pops contemplating a Black-skinned God and praying for an act of that God to “set men free.”

Though Armstrong had publicly criticized President Eisenhower for failing to enforce the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown vs. Board of Education (desegregating public schools), he had not been as vocal as other Black musicians in speaking out for civil rights—at least not when speaking to the mainstream press.

“Armstrong really didn’t ever say, ‘Hey, I should play at this benefit’ or ‘I should go with Harry Belafonte and march at the White House,’” Hatschek told me. “I don’t think that’s how he saw himself in that regard. I think he saw himself as trying to bring people together through his music and speaking out to the African American community and audience through magazines like Ebony and Jet and the Pittsburgh Courier….”

In his research for the book, Hatschek was “blessed” to connect with Armstrong biographer Ricky Riccardi, who is also the director of research collections for the Louis Armstrong House in Queens, NY. Among the archival materials in Queens were some 500 reel-to-reel tapes recorded in Armstrong’s dressing rooms at his gigs: conversations with friends and band members. Hatschek listened to them with fascination.

“He would comment on the headlines of the day,” Hatschek says of Armstrong. “He’d tell dirty jokes. He’d test dirty jokes on his friends.”

And Armstrong would talk about what a bitter “joke” it was that he’d been forbidden from playing in his native New Orleans because he led an integrated band (featuring white trombonist and vocalist Jack Teagarden).

It seemed at last that, with the development of The Real Ambassadors, this quintessential American entertainer was ready to bring his feelings about racial inequality front and center.

The Road to Monterey

As it turned out, The Real Ambassadors never enjoyed a run on Broadway, nor any fully realized theatrical production. Besides big problem number one—Joe Glaser—there was another major difficulty: No one had managed to complete a libretto. There was only really that story treatment written by Iola Brubeck. (Hatschek did find in the Stockton archives some pages of dialogue Iola had written, but this was only a stray fragment.) There was talk at one point of hiring an established writer to build a script for the show. Among the writers considered were novelist James Baldwin and playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Unfortunately, it all turned out to be just talk, although an ailing Hansberry was actually approached about the project not long before her death.

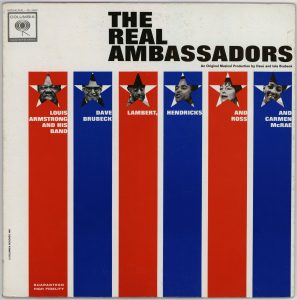

But the score for the show was ready to roll. And in late 1961, Columbia Records made a studio recording of it, with Armstrong as Pops and McRae as Rhonda. Dave Lambert, Jon Hendricks, and Annie Ross performed their spirited versions of what amounted to choral sequences. Members of both the Brubeck Quartet and Armstrong’s All Stars played in the sessions.

But the score for the show was ready to roll. And in late 1961, Columbia Records made a studio recording of it, with Armstrong as Pops and McRae as Rhonda. Dave Lambert, Jon Hendricks, and Annie Ross performed their spirited versions of what amounted to choral sequences. Members of both the Brubeck Quartet and Armstrong’s All Stars played in the sessions.

There was some concern about how to blend Brubeck’s innovative “West Coast” jazz sound (characteristically “cool,” “cerebral,” and “avant-garde”) with the more traditional East Coast Armstrong approach. Some titles in the score were written expressly for the show, but about 60 percent of the songs were recycled instrumental Brubeck numbers to which Iola had added lyrics. Howard Brubeck (Dave’s brother) put together some charts for the album, striving to make the two musical sensibilities merge.

“I think the Brubecks felt that they wanted to create a sound for this project that would let Armstrong be himself,” said Hatschek. “I think it worked on some songs, but not too well on others.”

One of the most moving moments of the recording sessions happened when Armstrong recorded the passionate “They Say I Look Like God.” According to Hatschek, Jon Hendricks remarked that when he heard Armstrong’s take on the song, “I felt like I was in church again.”

The score was later presented to a live audience in a “concert version” at the fifth annual Monterey Jazz Festival, on September 23, 1962. Iola, resplendent in a sheath dress and an elaborately embroidered stole, read a narration for the story between songs. Most of the cast from the album took part, although Annie Ross was replaced by Yolande Bavan. (Decades later, Bavan would write the foreword to Hatschek’s book.)

One critic wrote that Armstrong’s “glow” on that September night “radiated over the whole fast-moving [proceeding], lending warmth and credibility.” Another reviewer declared: “Monterey was ‘Louisville’ for a day.’”

To say the debut performance was a memorable experience is an understatement. When the Monterey Jazz Festival and the University of the Pacific celebrated the 50th anniversary of the show in 2012, Hatschek interviewed a few music lovers who’d been in the audience at that half-century-old performance, including a singer named Vera Algoet, who was 12 years old in 1962. She remembered the distant night in Monterey as something “transcendent.”

What’s left behind

With the passing decades (and with the eventual passing of Dave and Iola Brubeck), the show and its score seemed in danger of being forgotten altogether. But in recent years, concert versions something like the one in Monterey have been presented in Detroit, in Memphis, and at New York’s Lincoln Center. Hatschek was able to attend all but the Memphis staging, which, he notes, was performed in a cabaret club.

One of the problems with reviving the show, even in concert format, is that it has been so carefully tailored to the talents and personality of Armstrong that it’s difficult for any other performer to make the role of Pops his own. There’s even a song titled “Blow, Satchmo, Blow”!

In one of the interviews with Iola, Hatschek had asked her, “Did you ever wish that you had not associated the character of Pops so intimately with Louis Armstrong?”

She was silent for a moment and then said that, yes, she and Dave had considered that. But she added that they also wanted the show to be a tribute to the performer who’d achieved the highest level of renown while striving to live the American Dream. Hatschek followed up by asking Iola whether, instead of a star singer, they’d ever considered using an emerging Black stage actor from the early 1960s—James Earl Jones, perhaps—as Pops.

“Iola smiled and said, ‘We never considered that.’ In their minds, it was Louis or nobody.”

Apart from the idea of additional revivals, Hatschek suggested that jazz singers and cabaret artists alike might do well to look to the neglected Real Ambassadors score when making song selections for their shows. He pointed especially to two titles. One is the tender, nostalgic “Summer Song,” performed by Pops. (“It’s a beautiful change-of-pace song for an artist…” with an ending that is “wistful but optimistic, in my opinion.”) The second number is Rhonda’s saucy “My One Bad Habit.” (“I just hear so much the influence of Rodgers & Hart when I hear that, in the way the lyrics turn around.”) Incidentally, “My One Bad Habit” was inspired by an offhand remark Ella Fitzgerald had once made. Dave Brubeck insisted on giving Fitzgerald a writing credit for the song, something she found amusingly baffling. (Ella got the credit anyway, and her estate still gets checks for the song, Hatschek noted.)

Will there ever be a full-fledged theatrical version of this show, with a real book and real dialogue? Hatschek isn’t certain. He suggested that a more promising possibility would be some sort of production—perhaps a film—that would tell the story of Dave, Iola, Louis, and the others trying to bring The Real Ambassadors to life back in the days of Sputnik, James Dean, and West Side Story.

Having read this engaging book, I think that’s a splendid idea.

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.