Cabaret Setlist: “Blue Skies” — Music and Lyrics by Irving Berlin

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Article #15 in this ongoing series.

The simple-yet-engaging standard “Blue Skies” has the distinction of being the most successful Irving Berlin number ever to debut in a Rodgers & Hart musical.

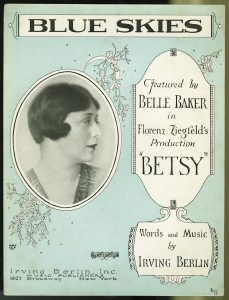

It’s not clear exactly when Berlin had begun composing the song, but, according to biographer Lawrence Bergreen, the first eight bars of an unfinished version of it had been packed away in his proverbial (and perhaps actual) trunk back in late 1926, when he received a call from musical theatre star Belle Baker. She was then rehearsing for the opening of Betsy, one of two musicals with a Rodgers & Hart score that were set to debut that holiday season. The other was Peggy-Ann. (Back in those years, every other musical seemed to be named after its female protagonist.)

“There isn’t a ‘Belle Baker’ song in the score,” the star complained, “and I’m so miserable.”

Berlin felt that “Blue Skies” could be just the ticket. He, Baker, and Baker’s husband, Maury, worked through the night to complete the song, but it was no easy task: Berlin had difficulty finding the right melody for the bridge.

Berlin felt that “Blue Skies” could be just the ticket. He, Baker, and Baker’s husband, Maury, worked through the night to complete the song, but it was no easy task: Berlin had difficulty finding the right melody for the bridge.

The finished piece was promising, but there seemed no way for it to be included in Betsy. Part of the contract that the show’s producer—Florenz Ziegfeld, no less—had made with Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart was that no outside songs could be inserted into their score. Baker, however, refused to appear in Betsy if “Blue Skies” was not included.

Ziegfeld agreed to the interpolation, but he made it clear that nothing about it should be mentioned to Rodgers & Hart (as though the duo wouldn’t notice the song’s inclusion on opening night?). “Blue Skies” was indeed folded into Betsy, where it became the only song in the score to register with the audience.

And did it ever register! According to Bergreen, the applause on opening night prompted a total of 24 encore choruses. Hart biographer Frederick Nolan reports there were 28.

As Nolan describes the incident, Rodgers and Hart “slunk off” in opposite directions after the Betsy premiere. The incident caused hard feelings between them and Berlin for some time afterward. Rodgers conceded in his autobiography, Musical Stages, that the Berlin number was superior to anything he and Hart had come up with for the show (which closed after 39 performances). In retrospect, Rodgers put the blame on “Flo”:

“A few words in advance might have eased our wounded pride, but Ziegfeld could never be accused of having the human touch—at least not where men were concerned.”

What Kind of Blue?

After its peculiar debut, “Blue Skies” was off and running. The number would go on to have one of the most impressive and varied histories in American Songbook lore—turning up in various guises over the decades.

Here is an early take: George Olsen’s largely instrumental version from April of 1927. It provides an idea of how folks in the 1920s came to know the song: Listen here.

Again, it is not a complicated song, though it has some unusual features. The critical response to its musical and lyrical content has been mixed.

Alec Wilder, in American Popular Song, seems dismissive of the number. “For me,” he writes, “its only distinction lies in its moving from a minor to a major key” (something that happens in each “A” section of the “A-A-B-A” refrain). “It is a great favorite with jazz musicians,” he continues, “I suppose because it gives them lots of room to move around in while improvising.” Wilder may have been thinking of Thelonious Monk’s “In Walked Bud” (1958), which used the musical underpinnings from “Blue Skies” as its basis. Hear it for yourself.

Wilder notes that he’s long been “puzzled” as to why “Blue Skies” begins in a minor key, as the word “blue” is used with its sense of “sad” only in the chorus’s last statement. (“Blue days, all of them gone….”) However, the critic ignores the song’s opening verse, which does, in fact, include the negative connotation of “blue,” from the very first bar:

I was blue, just as blue as I could be.

Ev’ry day was a cloudy day for me.

Then good luck came a-knocking at my door.

Skies were gray, but they’re not gray anymore.

Vocalists’ exclusion of this verse is understandable, given the pedestrian rhymes, ho-hum sentiment, and run-of-the-mill melody. This first of the song’s two verses is seldom included in recordings. One exception is this 1927 rendition by singer Irving Kaufman. (Can this guy ever roll his “R”s!): Hear this prolific artist from the 1920s.

The song’s second verse has, arguably, something relatively more interesting going on lyric-wise. But singers include it as part of the song even less often than they include the first verse. Here’s verse 2:

I should care if the wind blows east or west.

I should fret if the worst looks like the best.

I should mind if they say it can’t be true.

I should smile, that’s exactly what I do.

In his book Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists, Philip Furia finds appealing in Berlin’s song the very things that Wilder finds frustrating. Furia uses “Blue Skies” to support his point that Berlin wrote with more “intricacy and subtlety” than most of his fellow 1920s balladeers. Composer Berlin’s frequent shifts from minor to major key during the chorus of “Blue Skies,” Furia suggests, work in tandem with lyricist Berlin’s ambivalence in his use of the word “blue.” The song, he says “sounds sad and ‘blue’ even as its words celebrate gloriously ‘blue’ skies.”

“Days Hurrying By”

Following the song’s brief exposure on Broadway, the number turned up, in short order, where many a Shubert Alley title has turned up: in motion pictures. In this case, though, it wasn’t just any movie. The famously megalomaniacal Al Jolson would sing it in the film credited as marking the beginning of the sound era in the U.S.: 1927’s The Jazz Singer. Nowadays, this motion picture is about as un-“woke” as one can get, what with its portrayal of blackface performance. But it remains a fascinating historical artifact.

Following the song’s brief exposure on Broadway, the number turned up, in short order, where many a Shubert Alley title has turned up: in motion pictures. In this case, though, it wasn’t just any movie. The famously megalomaniacal Al Jolson would sing it in the film credited as marking the beginning of the sound era in the U.S.: 1927’s The Jazz Singer. Nowadays, this motion picture is about as un-“woke” as one can get, what with its portrayal of blackface performance. But it remains a fascinating historical artifact.

“Blue Skies” is heard in one of several musical sequences utilizing recorded sound synchronized with moving image. Jolson portrays Jakie Rabinowitz, the “jazz”-singing son of a disapproving cantor. In the scene where it is performed, the persistently effusive Jakie promises his mama a new house, some smart new outfits, and an excursion to Coney Island if she’ll go along with his showbiz aspirations.

Watching this number in 1927 must have been both revelatory and a bit jarring. Musical theatre historian Ethan Mordden identifies something less than appealing in the way the sequence is staged and, especially, in Jolson’s frantic interaction with Eugenie Besserer, who plays Jakie’s mother. Mordden writes in his book, The Hollywood Musical, that Jolson’s spoken passage here is “a paragraph of manic filial gush”:

“Besserer tries to keep up with it all, but she looks edgy and her murmured replies sound like cries for help. ‘Take me out of this movie!’ she seems to plead, but history was manning that mike, and nobody moved.”

The song’s popularity continued throughout the next several decades. Among those who recorded it were Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, Doris Day, Dinah Washington, and Della Reese. Bing Crosby brought it to the big screen again where it became the title song of a 1946 Paramount all-Berlin jukebox musical. Blue Skies focused on a love affair involving Crosby, Joan Caulfield, and Fred Astaire: Watch here.

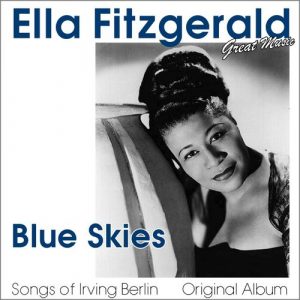

Ella Fitzgerald recorded a memorable 1958 iteration of the song for her endearing and enduring Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Irving Berlin Songbook. But “Blue Skies” didn’t make the cut on the original edition of the Songbook. It instead turned up on Fitzgerald’s 1959 album Get Happy! The track contains an especially athletic scat-singing turn, during which the singer incorporates snippets of Richard Wagner’s “Bridal March” (from Lohengrin) and George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” The track was later included in a reissued version of the Berlin Songbook: A “Blue Skies” swing with Ella.

Ella Fitzgerald recorded a memorable 1958 iteration of the song for her endearing and enduring Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Irving Berlin Songbook. But “Blue Skies” didn’t make the cut on the original edition of the Songbook. It instead turned up on Fitzgerald’s 1959 album Get Happy! The track contains an especially athletic scat-singing turn, during which the singer incorporates snippets of Richard Wagner’s “Bridal March” (from Lohengrin) and George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” The track was later included in a reissued version of the Berlin Songbook: A “Blue Skies” swing with Ella.

In the second half of the 20th century, the song resurfaced as a country hit, when it was released as the second single (following “Georgia on My Mind”) from Willie Nelson’s 1978 album Stardust, produced by Booker T. Jones. Nelson wasn’t the first country singer to make an impression with the number. Jim Reeves had done so in 1962, as had Bob Dunn and his Vagabonds—along with vocalist Moon Mullican—back in 1939: Listen to this early country-style “Blue Skies.”

When reviewer Jonathan Pappadarlo revisited the Stardust album in 2013, he maintained that Jones was smart to give Nelson “a more muscular arrangement [than he’d had on ‘Georgia’] to complement his somewhat free flowing vocal.” Listeners enjoyed the track, too. It went to Number 1 on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart. It remains a compelling version, despite the fact that Nelson repeatedly botches the “blue birds” portion of the lyric: Hear Nelson’s more contemporary interpretation.

If you look at YouTube’s comments section for any given “Blue Skies” recording, you’re likely to find such remarks as “I’m here because of Picard” or “Data’s death brought me here.” What’s that all about?

Turns out that the 2002 film Star Trek: Nemesis features the song, which is performed in the movie’s opening sequence by the Android Data (Brent Spiner) at a wedding reception: Watch it here.

Later, in television’s Star Trek: Picard, the song was used by the franchise again, this time in a dream sequence featuring the late Data.

Some recent admirers of the song apparently came to know it because of such vehicles as the 1998 film Patch Adams (in which Robin Williams sings lines from it, a cappella) and the trailer for the 2017 online series Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events (Doris Day version). The song has also been heard on the current NBC television series This Is Us, where it was sung by Gerald McRaney: Have a peek.

Bending, Not Breaking

It’s no surprise that, over the years, recordings of “Blue Skies” have been made by several Bistro Award recipients, including Nancy LaMott, Lainie Kazan, Sam Harris, Philip Officer, and Joyce Breach.

Another Bistro Awards honoree, Stacy Sullivan, agreed to discuss the song with me. Having grown up in a very musical family, she says she would first have heard the piece very early in her childhood. But she first took close note of it at age 13, when Nelson’s album came to her attention:

“I loved how he made something so old sound so new. It wasn’t just the arrangement that helped contemporize it for me; it was his connection to the lyric, making it sound as if it were written yesterday. I have to say, his influence on my music and career began with that album and continues to this day.”

She first performed the song in My Romance: A Country Cabaret, a show at the Cinegrill in Hollywood, with Andrea Marcovicci as her director. That show morphed into Sullivan’s 2008 CD It’s a Small Town. Her country-tinged take — arranged by Ed Martel—opened that album. Listen to Stacy here.

Sullivan, like Philip Furia, values the ambiguity in the use of the word “blue” in Berlin’s lyric:

“I love the complexity of ‘blue.’ It’s a word with many connotations. There is a sunny optimism about the lyrics, but the line ‘Blue days, all of them gone’ reminds me of someone trying to talk themselves into believing today is going to be a better day than yesterday.”

She thought about including the first of the two verses in her rendition, but ultimately decided against it. “It sort of gave away the intention underneath the refrain. I like the mystery.” She says she’s never heard anyone perform the song’s second verse.

Sullivan revisited the title in her 2014 tribute show, On the Air: Songs for Marian McPartland. Bistro winner Jon Weber was at the keyboard for this version, in which he and Sullivan wedded Berlin’s song with Miles Davis‘s “So What.” Here, understandably, Sullivan took a much different approach than on her “country” version of “Blue Skies.”

“My friend Eric Yves Garcia said something like, ‘Standards are resilient. You can bend them and they don’t break.’ I love to bend songs in my work. ‘Blue Skies’ is a perfect song. You can take it country or you can take it jazz, and it still has great integrity.”

Noting that the word “love” appears only once in the song (“Noticing the days hurrying by, / When you’re in love, my how they fly.”), I ask Sullivan whether she considers “Blue Skies” to be a love song.

“Being ‘in love’ is a roller coaster ride of emotions. Love can bring on the blue skies, but it can also bring on the blue days. I think it is definitely a song about love—and all that entails.”

For Sullivan, the pleasures of singing the number outweigh any challenges it presents:

“Most people have a historical connection to ‘Blue Skies,’ so that’s helpful when your drive is to reach out to those in your audience and make an emotional connection. The song gives you a head start, if you will, as it is familiar and loved. It’s almost ‘hymn-like’ in its accessibility and simplicity. The challenge is to ‘make it your own’ while staying true to the original intent.”

Besides the two renditions of the song shared here, Sullivan once sang the number at Birdland, in a duet with Natalie Douglas. I ask if she has any plans to return to the song in future shows.

“’Blue Skies’ is always in my back pocket,” she says. “The possibilities are endless.”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.

A favorite bit of Blue Skies trivia: The intro, with it’s unhappy lyric, is in a major key. For the happier body of the song, Berlin switches to a minor. So unusual, so creative.