Cabaret Setlist: “Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love” — Music by Henry Tobias, Lyrics by Billy Rose

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Article #17 in this ongoing series

We learned recently that Beanie Feldstein will headline next year in a Broadway revival of 1964’s Funny Girl. Once again, the name of that musical’s central character, real-life entertainer Fanny Brice (1891-1951), will be on people’s minds and lips.

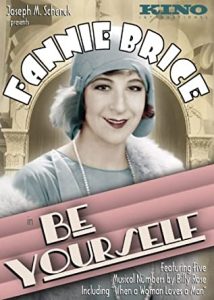

Brice’s career spanned from vaudeville to the Ziegfeld Follies to a long stint as radio’s Baby Snooks. But Fanny (or “Fannie,” as she was often billed) never had much luck performing in the flickers. Her cinematic debut was 1928’s partly silent backstager,” My Man. Most footage of that less-than-successful film remains lost today, although three reels were recovered in the 1990s.

In My Man, Brice sang many of her most widely known numbers, including comic novelties “Second Hand Rose” and “I Was a Floradora Baby.” And that much was fine. Fanny could out-clown most anyone. And whenever and wherever she sang the film’s title number, she could tug at listeners’ heartstrings and prod their tear ducts. But, according to Barbara W. Grossman in her 1991 biography, Funny Woman, Brice’s first film tanked at the box office largely because of the star’s lackluster performance in dramatic scenes. “In a full-length feature, particularly one with silent segments,” says Grossman, “her exaggerated mannerisms became monotonous.” The film initially did well in urban centers, but Brice’s Yiddish-inflected performance was not fully appreciated in rural areas. “Brice,” Grossman bluntly notes, “was too Jewish to play well in the hinterlands.”

She was soon back, however, with another starring role, in Be Yourself!—a United Artists film about a nightclub entertainer who manages (and also pines for) a prizefighter/souse named Jerry Moore (played by Robert Armstrong of King Kong fame). Released in March 1930, only a few months into the Great Depression, this full-blown talkie introduced several new songs, most of which are sung by Brice’s character, Fannie Field, on the stage of the nightclub where she works. However, “Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love”—today’s Cabaret Setlist selection—is sung winsomely by Fannie as she prepares Jerry’s morning meal. “Cooking Breakfast” creates an aura of swoony domestic bliss. In fact, I’d forgotten until I re-watched Be Yourself! recently that Fannie and Jerry are not spouses but just friends and business associates at this point of the film—though, obviously, lovestruck Fannie hopes for something more.

She was soon back, however, with another starring role, in Be Yourself!—a United Artists film about a nightclub entertainer who manages (and also pines for) a prizefighter/souse named Jerry Moore (played by Robert Armstrong of King Kong fame). Released in March 1930, only a few months into the Great Depression, this full-blown talkie introduced several new songs, most of which are sung by Brice’s character, Fannie Field, on the stage of the nightclub where she works. However, “Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love”—today’s Cabaret Setlist selection—is sung winsomely by Fannie as she prepares Jerry’s morning meal. “Cooking Breakfast” creates an aura of swoony domestic bliss. In fact, I’d forgotten until I re-watched Be Yourself! recently that Fannie and Jerry are not spouses but just friends and business associates at this point of the film—though, obviously, lovestruck Fannie hopes for something more.

Brice’s performance of “Cooking Breakfast” is a highlight of Be Yourself!—and, perhaps, the most winning few minutes in all of Brice’s slight filmography, despite the fact that she’s singing to doofus-y Robert Armstrong and not to someone with the suavity of, say, Omar Sharif.

The sticky fingers of Billy Rose

When you watch Be Yourself!’s opening credits, you’ll find the words “Music and Lyrics by Billy Rose.”

Rose’s involvement is not surprising. The irrepressible stenographer-turned-showman had not only helped negotiate Brice’s United Artists contract, but he had also married her, in February of 1929. That line in the credits, though, turns out to be what some people would term an exaggeration, and others would call a brazen porky.

Rose was frequently billed as a lyricist throughout his career, but he often worked with a collaborating partner or two. How much or how little he actually contributed to lyrical content probably varied from song to song, but Rose was notorious for taking more than his fair share of credit.

“That was to be his big trick: collaborating,” writes author Frederick Nolan of Rose in a biography of Lorenz Hart. “Get your name on the song, it didn’t matter how, just so you got a share of the royalty. Then go out and hustle it: get someone to print it, someone to plug it, someone to sing it in a show. Then collect.”

Still, claiming credit not only for the lyrics but also for the music of the Be Yourself! songs may have been too great a stretch even for Rose. Eventually Henry Tobias was correctly credited as the composer of “Cooking Breakfast.”

Tobias had initially met Rose in 1927 and had subsequently worked with him on a show called Padlocks of 1927, starring Texas Guinan. On that project, he had gained firsthand knowledge of the producer’s sketchy behavior regarding attribution. In his 1987 memoir, Music in My Heart and Borscht in My Blood, Tobias recalls his interactions with odd couple Billy and Fanny, shortly after their marriage. He describes being invited to their Manhattan apartment for bacon and eggs one morning, with Fanny wielding the spatula: “Billy remarked: ‘Say, Henry. This might be a good idea for a song, “While I’m Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love.” Here’s a dummy [lyric], and get busy with a tune.’”

The music that Tobias created did not, at first, pass muster. Perhaps because Rose knew he would be claiming the melody as his own work, he wanted to ensure it was high-quality stuff.

“It was only an eight-bar melody, but he was a tough man to please, a perfectionist to the last degree,” reports Tobias, “I always wrote my tunes easily. If they didn’t come easily they were no good to me, but he didn’t believe in that. He called it lazy writing and kept sending me back to try and try again. After several weeks of trying he finally accepted a middle strain.”

The lyric in the song’s film version differs slightly from the one Brice sings in a studio recording made at the time of the film’s release. In the movie, Armstrong joins in during the concluding measures of the song, to assert his preference for Grape-nuts (which he pronounces “Grape-Nouts”) over grapefruit. In the studio recording, the lyric in that slot has to do with the singer’s male companion drying the dishes and somehow managing to break them. Here’s the studio recording version.

Kimberly Faye Greenberg—whose one-woman show, Fabulous Fanny Brice, recently returned to New York City (and is also streamed online occasionally)—came to learn of “Cooking Breakfast” through Be Yourself!. She feels that the film’s rendition and Brice’s studio version both have their respective charms: “I find the movie version a bit more endearing in nature, the recording a bit more lively…showcasing the singing voice.”

Greenberg’s own performance of the song casts Fanny in a kittenish mood. She even steps out into the audience for some innocent but spirited flirtation.

In his 1992 study, Fanny Brice: The Original Funny Girl, biographer Herbert G. Goldman points out that Brice sings the first part of the song “straight” and the latter part with her robust Yiddish accent: “The song contrasts a woman’s love for the sweet ‘married’ life with the comedienne’s self-parodying, divorced perspective, echoing the two Brice viewpoints—Fanny the romantic and Fanny the cynic.”

Incidentally, that same mix of sincerity and parody comes through in one of the songs that Jule Styne and Bob Merrill wrote for Funny Girl. It’s my guess that Styne and Merrill used “Cooking Breakfast” as the model for “Sadie, Sadie,” a paean to (and burlesque of) domestic harmony that Barbra Streisand sang in both the Broadway and film versions of the musical. Greenberg, believes my hypothesis could be correct:

“Honestly, I think many of the tunes in Funny Girl are paying homage to [Brice’s] real-life tunes. ‘Rat-Tat-Tat-Tat’ pays homage to a lot of her Yiddish shtick, and ‘The Music That Makes Me Dance’ pays homage to ‘My Man.’ So, it makes perfect sense that ‘Sadie, Sadie’ could be inspired by ‘Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love.’”

Joining the “Breakfast” club

Soon after the release of Be Yourself! (which, by the way, turned out to be another box-office disappointment), several covers of “Cooking Breakfast” kept the song in the public ear, at least for a time. Bernie Cummins and His New Yorker Hotel Orchestra, for instance, released a 1930 dance version, with vocals by Belle Mann. Here, the number is billed as a “Fox Trot,” and Tobias (not Rose) is given the composer credit. Because of the dance slant of the recording, this version is considerably livelier than either of the Brice renditions. Note that, at one point, the musicians play the song’s short introductory verse (“Morning, I’ll be getting up…”), but Mann never sings it. Listen here.

Soon after the release of Be Yourself! (which, by the way, turned out to be another box-office disappointment), several covers of “Cooking Breakfast” kept the song in the public ear, at least for a time. Bernie Cummins and His New Yorker Hotel Orchestra, for instance, released a 1930 dance version, with vocals by Belle Mann. Here, the number is billed as a “Fox Trot,” and Tobias (not Rose) is given the composer credit. Because of the dance slant of the recording, this version is considerably livelier than either of the Brice renditions. Note that, at one point, the musicians play the song’s short introductory verse (“Morning, I’ll be getting up…”), but Mann never sings it. Listen here.

Annette Hanshaw’s version (also 1930), performed with Jack Albin and His Hotel Pennsylvania Music, is similar to the Cummins/Mann cover. The sprightly, appealing fiddle accompaniment to Hanshaw’s easygoing vocals is perhaps this rendition’s major distinction. Listen here to Hanshaw while watching the antics of Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton “making breakfast.”

Annette Hanshaw’s version (also 1930), performed with Jack Albin and His Hotel Pennsylvania Music, is similar to the Cummins/Mann cover. The sprightly, appealing fiddle accompaniment to Hanshaw’s easygoing vocals is perhaps this rendition’s major distinction. Listen here to Hanshaw while watching the antics of Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton “making breakfast.”

A final 1930 take on the song comes from jazz and blues singer Lee Morse. The version is notable mostly for its  flamboyant piano solo, embellished with playful glissandi. The no-nonsense sound of Morse’s voice suggests she is someone who may have slung her own fair share of “hen fruit on a raft.” Listen to Morse here.

flamboyant piano solo, embellished with playful glissandi. The no-nonsense sound of Morse’s voice suggests she is someone who may have slung her own fair share of “hen fruit on a raft.” Listen to Morse here.

After this flurry of 1930 covers, “Cooking Breakfast” seems to have entered a long period of dormancy. Singer Maria Muldaur finally revived the title as the opening selection on her 1983 Sweet and Slow album. This uptempo version is frenetic, syncopated fun: an appealing revival that demonstrates the song’s capacity for alternative interpretations. The track gets much of its energy from singer-songwriter Dr. John (John Rebennack), who handles the piano part.

Muldaur drops the rhyme “shucks”/”Lux” from the original lyric sheet, perhaps because Lux laundry flakes (the substance accidentally sprinkled onto the oatmeal in Rose’s original lyric) were not as widely known as they’d been in 1930. Unfortunately, the new words inserted—“yuck” and “salt”—have certainly never been paired in anyone’s rhyming dictionary ever. Tap your feet to Muldaur’s version.

Muldaur drops the rhyme “shucks”/”Lux” from the original lyric sheet, perhaps because Lux laundry flakes (the substance accidentally sprinkled onto the oatmeal in Rose’s original lyric) were not as widely known as they’d been in 1930. Unfortunately, the new words inserted—“yuck” and “salt”—have certainly never been paired in anyone’s rhyming dictionary ever. Tap your feet to Muldaur’s version.

In 2008, late in her career, Barbara Cook recorded “Cooking Breakfast” in a razzmatazz-y arrangement that enhances her gentle-but-jaunty vocal. Like some of the other versions here, this one inserts the verse after the first statement of the refrain. Cook, too, makes some noteworthy alterations to the lyric. She, like Muldaur, replaces the Lux soap flakes with salt, which she rhymes with “Oy gevalt!” And, more significantly, both she and Muldaur, make an adjustment to this lyric:

My baby is happy.

No wonder I’m happy,

When I’m cooking breakfast

For the one I love.

These late–twentieth century performers change the “I’m” in the second line to “he’s.” Perhaps this was meant to give the female protagonist a less subservient aspect: to make her more than a fixture in the kitchen. According to the original lyric, however, the kitchen chores in the song’s scenario seem to be split fairly between the woman and her fella. As earlier mentioned, the guy pitches in and wipes the dishes (albeit to disastrous effect). In any case, the lyrical switch here may diminish slightly what is perhaps the song’s most appealing element: a celebration of the joy that can come from doing for others. Cookin’ with Cook!

These late–twentieth century performers change the “I’m” in the second line to “he’s.” Perhaps this was meant to give the female protagonist a less subservient aspect: to make her more than a fixture in the kitchen. According to the original lyric, however, the kitchen chores in the song’s scenario seem to be split fairly between the woman and her fella. As earlier mentioned, the guy pitches in and wipes the dishes (albeit to disastrous effect). In any case, the lyrical switch here may diminish slightly what is perhaps the song’s most appealing element: a celebration of the joy that can come from doing for others. Cookin’ with Cook!

That celebration is an element that Greenberg finds at the heart of the number: “This song seems to be one of the most memorable for my audiences because it’s so relatable to everyone…. [It] showcases what we as humans do to serve someone else when we are in love, no matter how silly or odd it may seem.”

Let’s hear it from the boys

Until recently, “Cooking Breakfast” seems only to have been recorded by women, with one notable exception. Jimmy Tolson, playing a juvenile nightclub singer in Be Yourself!, reprises part of the number late in that movie with a level of sophistication humorously out of joint with his tender age. Here’s a clip of Tolson’s performance, which is used as a lead-in to Brice singing “Kickin’ a Hole in the Sky” (Billy Rose, Jesse Greer, Ballard MacDonald) in an elaborate and strenuous production number. If this performance seems familiar, it’s probably because its staging was the apparent model for “(It’s Gonna Be a) Great Day”—sung by Streisand as Brice in 1975’s Funny Girl film sequel, Funny Lady. Watch it here.

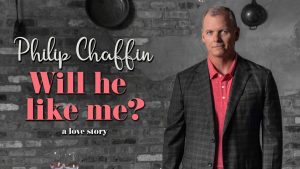

In 2018, Philip Chaffin included “Cooking Breakfast” on his fifth album, Will He Like Me? (a love story). The idea, he says, was “to create what I ultimately called ‘a gay love story’ but that, more specifically, was designated as a love story for the post-marriage-equality era.” (The album was honored with a Bistro Award in 2019.)

Co-producing Will He Like Me? (with Bart Migal) was Chaffin’s husband, Tommy Krasker. Most of the songs on this concept album were arranged and orchestrated by John Baxindine, but Krasker arranged “Cooking Breakfast.” Chaffin wanted the album to feel autobiographical, and one of the things he loves most in his own life is cooking for his husband. He had never heard the Rose/Tobias song until he Googled “songs about cooking” and the title popped up. “I then did a little research and discovered that it was sung by Fanny Brice—but really, at the start, I knew nothing about the song except that it really hit home.”

Co-producing Will He Like Me? (with Bart Migal) was Chaffin’s husband, Tommy Krasker. Most of the songs on this concept album were arranged and orchestrated by John Baxindine, but Krasker arranged “Cooking Breakfast.” Chaffin wanted the album to feel autobiographical, and one of the things he loves most in his own life is cooking for his husband. He had never heard the Rose/Tobias song until he Googled “songs about cooking” and the title popped up. “I then did a little research and discovered that it was sung by Fanny Brice—but really, at the start, I knew nothing about the song except that it really hit home.”

The new rendition of the song saw some lyrical changes, created by Krasker.

The Be Yourself! original, Chaffin notes, was written for a Jewish woman cooking for a Gentile man. But his own version finds a Gentile man cooking for a Jewish man. Krasker replaced “My baby likes bacon / And that’s what I’m makin’” with “He’s never had bacon / So that’s what I’m makin’.” Krasker also felt that the lyric about oatmeal sprinkled with Lux needed to go. He wrote a new release for the song, starting with the line “He says he wants a plate of blintzes.”

The updates seemed justifiable under the circumstances. “Having been the archivist for the Ira Gershwin Trusts for a decade, Tommy was always the first to say that songs like these were part of a vaudeville tradition where you tailored the material for the performer.” Enjoy it here.

Chaffin and Krasker found ways to tie this song, which is heard early in the album, to other titles on the song list. There’s an interlude in the middle of the track in which Chaffin merrily scats—in a “dum-duh-dum-dum” fashion—a few bars from Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s “Don’t Ever Leave Me.” The latter number is presented in a more serious context later in the album.

In another song near the end of the album, “Who Gave You Permission?” (Billy Goldenberg, Marilyn and Alan Bergman), Chaffin’s protagonist faces the sudden loss of his husband and sings, “I came down this morning and what did I do? / Went straight to the kitchen, cooked breakfast for two.” That lyric, too, serves as a clear callback to “Cooking Breakfast,” with the contrast enhancing the album’s poignancy.

Chaffin and Krasker had planned a live touring show of Will He Like Me? for spring of 2020, when they were living in Fort Lauderdale. Then COVID turned up.

“We’ve since moved to Palm Springs,” says Chaffin, “which also seems like a great place to premiere this show… so I’m hoping to get something rolling by 2022…. I truly can’t wait to do these songs in front of live audiences. I mean, songs like ‘Cooking Breakfast’ just call for an audience, you know?”

Down to the last morsel

I ask Greenberg and Chaffin what advice they would give to someone interested in singing this spry 91-year-old song.

Greenberg, who will next present her Brice show at Manhattan’s Green Room 42 on December 2, advises singers to concentrate on personal moments that can stir emotions during the performance of the song.

Chaffin advises anyone tackling “Cooking Breakfast” to “make the most of every second of it.”

“It’s such a lyrically dense song,” he adds. “There’s so much to play. So many shifts of emotion and points of view. Go for it all!”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.