From Logistics to Aesthetics: The Varying Roles of the Cabaret Director

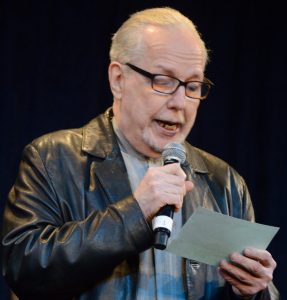

BistroAwards.com’s critic Gerry Geddes, also a cabaret director, has worn many hats that include writer, lyricist, teacher, and theatre director. He has no doubt about the major challenge cabaret directors face today.

Put simply: it’s the diminished values of the culture at large. More specifically, it’s what’s viewed and promoted as musical entertainment on such TV programs as The Voice and American Idol.

“It’s the screeching,” he asserts. “Singers have been screeching for years. Now, the screeching is written into the songs. It’s exponentially horrible. Bad performance brings fame. Mediocre performers who have nothing to say become super stars. It’s antithetical to cabaret which is all about honesty and authenticity.”

Cabaret directors have their work cut out for them, especially when dealing with newbie performers, many of whom need to be freed from the mainstream cultural influences, he says.

But even with more seasoned artists, directors face challenges—from structuring, to editing, to, most central, honing their client’s performance for the unique cabaret setting. The latter boasts its own aesthetic and logistical parameters.

“Performers who work in musical theatre sing to the balcony,” continues Geddes whose clients have included André De Shields, Darius de Haas, and Helen Baldassare. “In cabaret there is no balcony. Some performers sing with their eyes closed. In cabaret, their eyes have to remain open. Others hold the microphone in front of their noses, blocking much of their face. The audiences in a small space needs to see the singer’s mouth, especially with a new song.”

Today most cabaret performances include a director’s name on the program. They are viewed as essential, though at one time cabaret directors were anomalous, if not non-existent.

In the high-end nightclubs of yesteryear—arguably the cultural progenitor of today’s cabaret venues— performers sang a series of songs beautifully. That’s what the well-heeled, elegantly clad audiences came to hear. Performers largely directed themselves.

Depending to whom you’re speaking, the shift began in the late 1970s to the early ’80s, but either way, by the ’90s, and definitely the early aughts, cabaret directors had become a given.

Economics changed, competition grew, and the art form evolved into an array of new storytelling genres requiring new skills: creating a narrative throughline and mastering the art of patter for example.

Cabaret, as we know it today, gained gravitas and was no longer viewed as “slumming” even among those who were initially dismissive. Performers understood that they needed a third eye to guide them in this uncharted and somewhat more complicated territory.

In addition to Geddes, I spoke with five other cabaret directors: Jeff Harnar, Barry Kleinbort, Lina Koutrakos, Tanya Moberly, and Lennie Watts, all of whom are either award-winning performers and/or writers and found themselves directing almost accidentally. A student, a friend, or an acquaintance approached and asked for help in forging a show. Only one of our interviewees had engaged a director for his own act before becoming a director himself.

A repeated lament voiced by several directors was that outside of select theatre circles, few are entirely sure what they do. Actually, they do a lot. But short of establishing a real sense of mutual trust with the artist, there’s no one boilerplate.

Finding the Director Who “Gets You”

Some directors come on board at the tailend of the rehearsal process, others serve as collaborators from the outset. They may work with the musical director and, if there is one, the choreographer. They often help the artist select the songs, program those songs, and even tweak a note or lyric to make it the artist’s own. They can serve as facilitators among the players involved.

Directors are mindful of the size, design, and placement of the stage along with the configuration of the audience. The layout informs acting and singing choices. Same for lighting— or sometimes the lack of it— when it’s up to the performer to physically indicate the song has come to an end with a definitive bowing of the head, for example. Yes it’s a small gesture, but one of many not inconsequential details a director addresses.

But the director’s primary role is to fulfill the artist’s vision and within those parameters make that performer shine. “When I direct theatre, it’s the performer’s job to make my vision a reality,” says Lennie Watts. “When I direct cabaret, it’s my job to make their vision a reality.”

Of course that’s not always possible, especially if the performer’s persona, story, or songs are not in sync with the director’s sensibility.

Barry Kleinbort recalls a singer in one of his master classes who had rewritten the entire lyric to Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here,” substituting her own words about the challenges of being overweight and bulimic. Although Kleinbort is a strong advocate for making each song an original representation of the performer singing it, and has no problem with small adjustments, he found her rewrite an act of mind-boggling chutzpah. “She wanted me to tell her that her rewrite was a work of sheer genius,” he recalls. “Instead, I replied, ‘Lady, you got balls.’”

“Performers need to shop around for a director,” continues Kleinbort who is also a composer, lyricist, and librettist. “Don’t just settle on a director who is flavor of the month. You have to find the director who ‘gets you,’ who sees something in you. A director is the safety net who allows the performer to take risks. If they fail, I promise to catch them. Directors are also therapists and, occasionally, hand holders. My role is to help distill the performer’s personality in a one-hour show. Each song reveals another facet of that particular artist. The evening is a composite, every song like a tile in a mosaic.” Kleinbort has directed such luminaries as Len Cariou, Lorna Dallas, Anita Gillette, and Karen Mason.

“A lot of performers leave their imperfections and quirks at the door,” says Watts. His clients include such award winners as Meg Flather, Those Girls, and Gerrilyn Sohn, among many others. “I want to bring those imperfections and quirks back on stage. I’m not talking about revealing your deepest secrets. That’s therapy, not theatre. I’m a stand-in for the audience. If I enjoy and understand it, so will they. I once directed a cabaret performed in Spanish and I don’t know a word of Spanish, but it worked because I understand what was happening emotionally.”

“A good director gives the performer the space to create,” adds Jeff Harnar. “It’s the message and the way the message is delivered. Sara Lazarus, one of the earliest cabaret directors, was both a nurturing guide and a loving messenger.” Tovah Feldshuh, Rita Gardner, and Josephine Sanges are among those that Harnar has directed.

Lina Koutrakos says she directs a performer, including the likes of Ari Axelrod, Diane D’Angelo, and Susan Mack, in the same way she wants to be directed. “Anyone who directs me will know, see, and appreciate who I am and want to make me as good as possible. The first thing they have to do is validate me. That’s what I do with my clients.”

Still, earlier on in her career she admits imposing her vision on the performers. “I’d direct their shows as if it were mine. Just because it works for Lina doesn’t mean it works for anyone else. I don’t do that anymore.”

Getting Artists to Play Themselves and Break the Fourth Wall

Cabaret is distinctly different from theatre in that the performers are playing themselves even when they are playing someone else. They are exposing their emotional journey in song and story and have to be comfortable with that level of self-revelation, not to mention breaking the fourth wall and speaking conversationally to the cabaretgoers as if they’re chatting with old friends in a living room.

Some directors urge actors not to memorize the patter, but rather to allow it to emerge spontaneously. They agree that a cabaret audience must feel it has truly spent the evening with the performer who is essentially no different onstage than off-stage. At the same time, the performer cannot assume that everyone in the venue is conversant with their personal history. Sometimes a little backstory is necessary. It’s a balancing act.

A good voice is lovely, but good acting is far more important, I was told repeatedly. It can carry the song and may even compensate for a non-stellar voice. And that brings us to the motherlode in cabaret performance: the spoken and, oftentimes, unspoken narrative thread. What are you telling the audience and why? Obviously, this is a more pointed issue in an autobiographical show, but even in a tribute or solo piece where the performer assumes the icon’s persona it has the profoundest application.

One of the director’s top priorities is to get the clients to understand why they’ve chosen the songs they have. They can not simply serve as a vocal showcase or, worse, be employed because they elicit a wave of nostalgia and the concomitant enthusiasm in the audience. That’s cheating and not what cabaret is all about. At least it shouldn’t be.

Equally important, the artist’s connection to the song must come through the performance of that song, not the patter that follows or precedes it. In fact, an overload of information—often personal and confessional—can be distracting and uncomfortable-making.

“I do a lot of editing,” admits Tanya Moberly, who has directed Amy Beth Williams, Rian Keating, Marnie Klar and more. “Is what’s being said essential, stage-worthy, or isn’t it? Just because you like a song or a line of dialogue or an anecdote doesn’t necessarily mean it serves the show and should remain. A performer needs to be fearless. But I’m allergic to patter that’s self-indulgent or explains the song. The song is the emotional vessel that tells the story and reveals the artist. And if the performance makes me, not the performer, laugh, cry, and think—that’s golden.”

“I have to be a barometer of the audience’s reaction to what it hears,” says Kleinbort. “I had one singer who wanted to talk about the child abuse she endured. I warned her that the audience might not welcome the information, but she felt it was very important to tell her story. I stated that it would have to be placed late in the show so that we could build up to it. Come the performance, the big moment came. The audience froze. And she never got them back. The singer was heartbroken. She wanted to cancel the rest of the run, but I said, ‘No, we’ll fix the show. You’ve learned an important lesson. You have every right to say what you want in a show. The audience also has the right not to hear it.’”

Sometimes, the least—and most—a director can do is rein in the artist, tone down the overstated emotion and cut the excessive verbiage. Moving from theatre to cabaret is not unlike the toolset required in the transition from the stage to the screen.

When the Director Becomes Co-Creator

On the flip side, occasionally a director takes on the role of co-writer, reshaping a production and shepherding it to fruition. Harnar recalls collaborating with Tovah Feldshuh, who starred in “Tovah is Leona!” at 54 Below in 2019.

Originally titled, “Queen of Mean,” it was a Broadway-bound musical (Ron Passaro, music; David Lee, lyrics) inspired by the life of Leona Helmsley, mega-businesswoman/tax evading felon. Harnar re-conceived the musical as a one-woman cabaret show that finds a deceased Helmsley in purgatory. Determined to move on to heaven, she tries her case before a cabaret audience, wittily defending herself, at times from a feminist perspective, singing songs from the original in addition to relevant pop tunes, and ad-libbing away with the audience.

Harnar was awed by Feldshuh’s performance and, even more important, her commitment and level of preparation. In fact, like the others, working as a director has had an enormous impact on his own performing career.

“As a director I’ve been humbled by how brave and non-defensive the performers are,” says Harnar. “I’ve learned from all of them. In the end it has helped me stay open and be teachable as a director and performer, working with my directors.”

Looking into that proverbial crystal ball most of those interviewed suspect their jobs won’t change much down the road short of the ongoing need to familiarize themselves with an expanded musical repertoire that may or may not include American Songbook standards.

Whether they’re fans or not of the new crop of tunes, thanks to technology, they have easy access to the songs and their history. On another front, they anticipate that live streaming will become increasingly routine. As directors, that may require some small adjustments, but nothing major.

Always Busy, Always in Demand

Our directors don’t have a shortage of work. Indeed, their dockets are full. Harnar is helming Boston singer-songwriter Rene Pfister in October at Don’t Tell Mama; Becca Kidwell in November, also at Don’t Tell Mama; and Celia Berk in December at Urban Stages.

Kleinbort will be directing Karen Mason this month at Chelsea Table + Stage; in October, its Wendy Scherl at Chelsea Table + Stage; Madelaine Warren at the Laurie Beechman Theatre; and Jamie deRoy & Friends at Birdland.

For Koutrakos, it’s Susan Mack next week at Chelsea Table + Stage; Elvira Tortora at Don’t Tell Mama in October and November; and Margaret Curry at the Laurie Beechman Theatre in November.

Moberly’s upcoming shows at Don’t Tell Mama include Marnie Klar in October; Rian Keating in October and November; and Amy Beth Williams in November and December.

Watts is looking forward to his shows featuring, respectively, Meg Flather, Those Girls, Jill Senter, Lyle Smith Mitchel, Lynda Rodolitz, and Camille Diamond to be presented at At Don’t Tell Mama at various times throughout the fall.

Geddes career has clearly come full circle. In the coming months, he will be bringing back to Pangea—where he serves as artist in residence—his much praised “Selfies and Songs,” a musical autobiography of his early years in New York. He recounts his struggles as an aspiring performer and a young gay man in the ’70s on the cusp of the gay liberation movement. The piece coincides with the publication of his memoir, Did I Ever Tell You This? One of its stars, Andre Montgomery, was the first singer Geddes directed more than 40 years ago.

Like the others, Geddes says his goal is first “to present the performer in the most positive light and celebrate their strengths, and secondly, to create the show that I would most enjoy as an audience member while keeping my contribution as invisible as possible.”

Cautious optimism is the password among all our directors. Still, some are concerned about the ever growing financial demands placed on cabaret performers, limited and, more usually, non-existent coverage by mainstream press, and the shows’ short runs, thus limiting the time for artistic growth. That’s a problem right now and they expect it will only get worse.

No one has the answer for that one. It’s a topic that needs exploration.

###

About the Author

Simi Horwitz is an award-winning feature writer/film reviewer who has been honored by The Newswomen’s Club of New York, The Los Angeles Press Club, The Society for Feature Journalism, the American Jewish Press Association, and the New York Press Club (among others). She received an Honorable Mention from Folio: Eddie and Ozzie Awards for her two drag stories (May 22, 2020, August 4, 2020) published here on BistroAwards.com. More recently, she was the recipient of the 2023 New York Press Club Award and won three 2023 L.A. Press Club Awards., including first prize for film criticism (for reviews published in the Forward). The publications that have printed her work include The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Hollywood Reporter, Film Journal International, and American Theatre. She was an on-staff feature writer at Backstage for fifteen years (1997-2012).