Bistro Bits: This New Memoir Is Not a Drag; A Roundup of Cabaret Confessions

Charles Busch spills it.

A cabaret venue can sometimes seem pretty chameleonic.

Monday, you’ll find a singer performing a Burton Lane tribute. Tuesday you’ll get a comedic sketch show with no music at all. Wednesday’s headliner may turn out to be an entertainer whose work is indescribable but probably best tagged with a “performance art” label.

One reason for this seemingly infinite variety is that cabaret clubs frequently provide an oasis for performers who work principally in show-business realms outside of cabaret: pop singers, rock singers, classical singers, comics who have previously performed only in the relatively rough-and-tumble atmosphere of stand-up comedy clubs.

And actors. Manhattan’s 54 Below, of course, frequently provides musical-theatre triple-threats a chance to stretch: to present themselves to New York as themselves, sometimes, maybe, for the very first time.

Charles Busch has made a career primarily in the theatre, both as playwright and actor, most often taking on star-lady roles in shows he’s written, from Vampire Lesbians of Sodom to The Confession of Lily Dare. But he’s also frequently dipped a toe (or taken a bold, feather-rippling swan dive) into cabaret waters. Cabaret has been an ongoing component of his long career, and in early 2020—just before the pandemic—Busch was presented a special Bistro Award for his ongoing Creative Artistry in club shows.

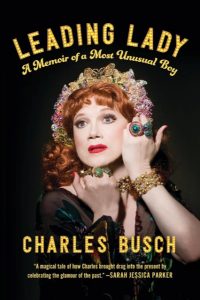

Now he reminisces—sporadically—about his cabaret adventures in a charming, funny, and evocative new book, Leading Lady: A Memoir of a Most Unusual Boy (SmartPop, 2023). He also shares his personal story, and covers other branches of his one-of-a-kind career, including forays into filmmaking and libretto-fashioning.

Early on, in the late 1970s, Busch sought to find an audience for a solo show called Hollywood Confidential, in which he played all the roles, in much the same fashion as legendary monologist Ruth Draper. He found rooms to play in Greenwich Village nightspots, starting at a club called Scene One, where he was hired by manager Bobby Kneeland.

Then, one day, on a Village stroll, he visited a newly reopened Duplex, where he met the late Erv Raible.

“Erv was a small dynamo,” Busch writes in the book. “He and his lover, Rob Hoskins, had been teachers at a performing arts high school in Cincinnati. In a bold move considered deranged by their academic colleagues, they quit their jobs, moved to New York and bought the moribund club. Erv spoke with a pronounced flat Midwestern accent and sizzled with ideas and plans.”

Raible employed Busch, who was soon part of a group of regulars appearing at the Duplex, including Bruce Hopkins, Ruby Rims, and Julie Kurnitz. He was impressed by the distinct artistic brand of each of those entertainers: “Their originality expanded the traditional concept of cabaret as exclusively the realm of song stylists and stand-up comedians.”

Soon assisting Busch with the development of his solo-performance talents was another cabaret stalwart: director Peter Napolitano. (All of this was before Busch’s big breakthrough with original theatrical confections at Theatre-in-Limbo in the East Village.)

Much later, in the 2010s, Busch, along with his pianist, arranger, and duet partner Tom Judson, resumed frequent club outings. As time went by, he adjusted his stage persona: performing without the customary wigs and reserving the elegantly styled gowns (and other fetching frocks) for his legit-stage roles. The move proved to be the right one at this stage of his career:

“My advice to those starting out in cabaret has always been to strive to present onstage as authentic a version of oneself as possible. If I intended to grow as a cabaret performer, it might be necessary to strip off that final veil of self-protection.”

And so he did, with a little boost from the late fashion-designer Michaele Vollebracht, who encouraged him to allow his onstage male persona to drip with shimmering beads.

More details about that—plus many more goodies—in the quick-to-be-turned pages of Leading Lady.

Lose the veils!

Three recent cabaret shows—all enjoyable, and all presented at Don’t Tell Mama—seem to illustrate both the wide-ranging variety in subject matter that can happen with the art of cabaret and the importance of authenticity and freedom from onstage camouflage that Charles Busch speaks of in his memoir.

Rian Keating in Woman Songs (directed by Tanya Moberly) looked at the idea of the “fallen woman,” something that fascinated, perplexed, and sometimes amused him as he came to learn about sex in his formative years. Keating began by looking at the partly real and partly surmised love lives of various female teachers of his. Here there was some distance between the narrator and the subject matter. But as the narrative continued, Keating went deeper. The culmination came when he described someone personally close to him who had faced the threat of sex shaming—an episode fraught with the danger of very dire consequences.

Newcomer Elvira Tortora presented a warm and often hilarious account of growing up with a Brooklyn bookie dad in The Bookmaker’s Daughter (directed by Lina Koutrakos). The show was full of laughs—a kind of screwball comedy about a loving family living just beyond the limits of the law. But Tortora was wise to include a few darker notes that expressed the downside of her childhood in a not-quite-legit world. In one scene she recalled a silent communication between herself as a teenager and the emotionally scarred girlfriend of a boxer who came to the Tortora home: a young woman not that far from her in age. Tortora’s performance of the wistful “Raining” from the musical Rocky (Lynn Ahrens, Stephen Flaherty) was a perfect way to illuminate this scene.

And, finally, there was Jason Henderson’s Getting to Noël You (directed by Barry Kleinbort). An update of a program that the New Zealand–born performer presented before the pandemic, the show featured a series of songs by Noël Coward, used to illustrate Henderson’s points about working life in our own era, particularly the “temp” working life in urban office settings. Though no fault of his own, Henderson faced a problem with this theme. The show seemed far more relevant before the COVID scourge, when office life still bustled and working remotely was rare. (The inclusion of Coward’s song “Twentieth Century Blues,” sung nearly a quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, underscored this problem.) Henderson, for the most part, kept a distance from the material, looking at things with a sometimes amused, sometimes bemused eye. On the one hand, that’s very Coward-y. But it also kept a sort of screen between him and his listeners. Fortunately, authentic connection was made when Henderson sang some of Coward’s more heart-on-sleeve ballads and—especially—near the end of the show, when he talked about his own life during the pandemic and his struggle to get back to New York to get on with his training and his career. Henderson—whose lilting, flexible singing voice is more impressive than ever—may never be a “confessional” sort of storyteller, but I hope he’ll go further in this direction: peeling back some of the veils of self-protection that Charles Busch writes of in his memoir. (Read Gerry Geddes’s review of Getting to Noël You here.)

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.