Bistro Bits: Rolling Back the Years—with Mary Hopkin, Dory Previn, and Eydie Gormé

The songs, sonatas, and symphonies we gravitate to early in our lives set in motion our own particular musical educations. If we hear and love Mozart or The Grateful Dead or Dolly Parton early on, we’re likely to seek out other music makers in the same general bucket. Of course, we may outgrow or otherwise turn away from those early preoccupations, wondering why we were so smitten with them. But it feels wrong somehow to toss out those youthful touchstones altogether.

Recently, I had a look at three albums of recordings from my younger years—one album each from the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s. And here’s what I discovered.

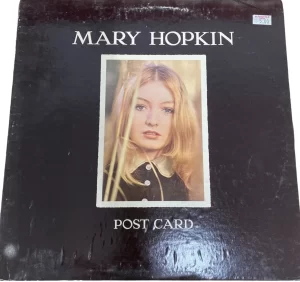

Mary Hopkin, Post Card (1969)

If you were around and sentient in late 1968, you’ll certainly remember “Those Were the Days,” as sung by Welsh singer Mary Hopkin. The song crops up now and again in cabaret shows, where it seems to invite an audience sing-along. The folky tune—with lyrics that explore the peculiar allure of nostalgia—was played to death on top-40 radio stations: an anomaly on music charts at a time when soul, R&B, and rock music of various stripes (bubble gum to heavy metal) predominated. Though the song was produced by Paul McCartney, its melody was that of an old Russian song, dating back to the early years of the 20th century.

The tune went to #1 on the U.K. and Canadian charts, and peaked at #2 in the states, right behind the Beatles’ “Hey, Jude.” (That must have been a good week for still-a-Beatle Paul.)

After her success with the single, the young, breathy-voiced, yellow-blonde-as-a-baby-chick Hopkin released the album Post Card, also produced by McCartney, in early 1969.

My brother Brian and I listened to Post Card a lot—I more than he. I don’t recall which of us purchased the disc or whether it was a gift. Collecting records was pretty new to us in those days, but we enjoyed listening to music in the basement of our rural Oregon home. I liked show tunes and the Fifth Dimension. Brian was drawn to rockier bands, like the Guess Who. Together, we had worn out The Smothers Brothers at the Purple Onion, all but memorizing it word for word and note for note. Some of the adult jokes from Dick and Tommy went over my head, and I was intrigued at times by what made the audience howl. (Eventually, I figured it out.)

Though I knew very little about pop music at the time, I understood that Post Card was an eclectic collection of songs. Also, I was struck by the idea that this singer was so young. In fact, at 15, I was a mere four years younger than Mary! It was cool knowing that someone that unseasoned could be such a surefooted performer, singing to the whole wide world.

The songs from the album that made the biggest impression on me—and that lingered in my memory over the years (aside from “Those Were the Days”) —were “Lullaby of the Leaves” (Bernice Pelkere, Joe Young) and “There’s No Business Like Show Business” (Irving Berlin). It wasn’t until I began to learn something about jazz that I came to know that the haunting “Lullaby…” was a vintage jazz standard. As for “…No Business…,” I understood from television that it was the anthem of the entertainment industry. But, did I know, in 1968 or 1969, that it was an Ethel Merman signature song? Or that it was from a Broadway musical? I’m not sure. I recognized, though, that something differed in Hopkin’s rendition from what I’d heard on an Ed Sullivan or a Red Skelton show. It was a bit slower and more thoughtful, with a driving rock beat, and I paid as much attention to the verses as to the famous refrain. Listen to Hopkin sing it HERE.

When I went back to review the album recently, I found that I still liked those two songs, especially the dreamy accompaniment of cool flute and meandering guitars and cello on “Lullaby…” and the grand, rocking arrangement for “…No Business….” To those two numbers, I’d add a third standout: George Martin’s “The Game,” a simple but sweet and melancholic waltz ballad with lots of calliope.

Hopkin’s whispery moments now sound to me a bit limp in places—some have suggested that her voice was too “folky” for some of the album’s material. She sounds better, I think, when she’s singing not wistfully but with determination and purpose—either that or with a gleeful lilt. Still, I love her sweetness and sincerity throughout. And the album demonstrates how well McCartney was versed in British pop music traditions, especially in a number like “Love Is the Sweetest Thing” (Ray Noble), presented straightforwardly as the classic British pop tune from the 1930s that it is, rather than as a tongue-in-cheek sendup of 1930s sounds. The clippity-clop horse effect on the instrumental interlude is especially endearing. HERE’s a link.

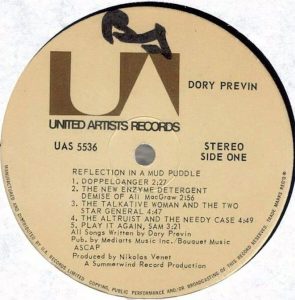

Dory Previn, Reflections in a Mud Puddle (1971)

By the early 1970s, I was away at college, although by “away” I mean at a state school in a small town maybe 75 minutes from my parents’ home and the stereo in the basement. I was studying the arts and literature, and one of my favorite professors was Sandy Sessum. She was, in a way, reminiscent of Mary Hopkin: young and fair, with long, straight blonde hair. She was also smart and encouraging—and I was nuts about her. Her American Lit course was one of my favorites, especially when we read Frank Norris’s McTeague, which I found spellbinding. (I thought it would make a good movie, oblivious to the fact that it had been famously filmed decades earlier as the silent Greed, directed by Erich Von Stroheim.)

It may have been in that particular lit course—or possibly in a poetry course—that Ms. Sessum brought in lyrics from contemporary songs, which we examined with the same attention we would give to T.S. Eliot or Ann Sexton. I remember loving our discussions of the lyrics of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne.” There may have been some Gordon Lightfoot and Buffy Sainte-Marie in the lesson plan, too.

But my introduction to the very confessional lyrics of Dory Previn was what most enthralled me. I remember learning about the whole Dory Previn / Andre Previn / Mia Farrow love triangle, and Dory’s curt response to that scandal with the song “Beware Young Girls.” The class also spent some time with the title song from Dory’smusical revue and album Mary C. Brown and the Hollywood Sign (1972). But it was the 1971 album Reflections in a Mud Puddle that stood out most, and I had to have a copy of my own. As with Post Card, I listened repeatedly, absorbing every inflection on every note.

It’s a short album. Side 1 includes only five tracks, while Side 2 is even briefer, consisting of a 12-minute suite of related songs called “Taps Tremors and Time Steps.” It explores Previn’s troubled relationship with her emotionally disturbed father.

The two songs I most remembered a half century later came from Side 1. “Doppelganger” is the opening track: a frantic, desperate stream of paranoia about a mad killer living in our midst. (The song’s title provides a clue to who the depraved figure really is—something revealed in the last line.) The fifth and final song on Side 1 was “Play It Again, Sam,” a lazily loping piano-bar number that looks at nostalgia with a much more jaundiced eye than Hopkin’s “Those Were the Days.”

In fact, “Play It Again…” owes more to a totally different song called “Those Were the Days”: the one performed by Archie and Edith Bunker during the opening credits of television’s All in the Family (which had debuted in 1970). Like that song, “Play It Again…” examines the ways we whitewash difficult truths when looking back at things, filtering it all through faulty, shifting memories:

Play it, Sam. Play it again.

Take me back to you know when.

Let’s hear it, Sam,

For good old World War Two.

Like “Doppelganger,” “Play It Again” operates like an unfunny joke with a bitter punch line—a kind of “punch-in-the-gut” line, really. Hear Previn’s song.

I wound up sharing my new discoveries with my high-school English teacher at one point, and she was not impressed. She wasn’t fond of the confessional nature of the songs. She found them self-indulgent.

Actually, I don’t entirely disagree with her now, especially as the charge applies to “Taps Tremors and Timesteps,” which brims with some fairly naked self-pity (tempered, though, by some sharp wit).

On the other hand, harsh criticism of “confessional” songwriters—especially female songwriters—seems unfair. What poets worth their salt shy away from self-examination? Think of all the “I” poems in standard poetry anthologies: “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” “I Sing the Body Electric,” “I Heard a Fly Buzz When I Died.” Why pick on lyricists like Previn (or Janis Ian with “At Seventeen” or, maybe, Billie Eilish these days) for turning inward? While posterity may have granted Emily Dickinson and her buzzing housefly an exception to the rule, in the case of Previn and other female poets and lyricists, sexism, at least in part, seems to have been part of what provoked the critical ire.

But in “Play It Again…” and in another song from side 1, “The Talkative Woman and the Two-Star General,” Previn is not so introspective. The latter song is clearly a response to the Vietnam war. In it, a very chatty woman engages in conversation with a military man who is apparently eager to cut her off. But her prattling on about “colors”—particularly various shades of red—reveals her to be not as dotty as she seems. At least, not dotty to the listener— the general will likely never see her simple wisdom. Previn expertly steers the story-song narrative, keeping it alive at every moment. Listen to “The Talkative Woman…” HERE.

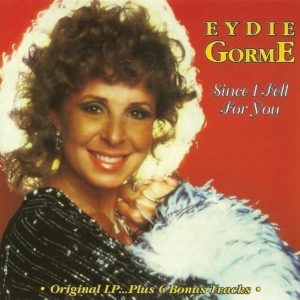

Eydie Gormé, Since I Fell for You (1981)

By 1981, I had been living in San Francisco for five years. I had wrapped up my studies at a Stanislavski-based acting program and had taken my first proofreading job, for Deloitte, Haskins & Sells. I shared a large, mouse-riddled Guerrero Street apartment with two roommates.

One of them, Doug, worked in the classical department of Tower Records. So, yes, we heard a lot of Puccini and Verdi. But he brought home all sorts of albums from Tower. He was nuts about Sinatra, so I heard many playings of Old Blue Eyes’ classic albums—both the swinging ones like Ring-a-Ding-Ding! and the saloon-ballad ones like In the Wee Small Hours. Ella Fitzgerald was another favorite, especially all of her magnificent “songbook” albums. And, thanks to Doug, I was also fortunate to hear both Frank and Ella perform live: he at the Circle Star Theater in San Carlos, she at the Concord Pavillion.

One of the best albums that Doug brought to the apartment, though, was this short, sweet album from Eydie Gormé. Since I Fell for You was only 10 cuts long, but it displayed all the splendor of Gormé’s wide-ranging, powerhouse voice. (The album was produced by Don Costa for the small label Applause and was Gormé’s first English-language solo album in several years. In a re-release some years later, six more songs were added to the lineup, but the original album was just 10 songs.)

The track from this disc that made the biggest impression on me was Eydie’s version of “God Bless the Child,” written by Billie Holiday and Arthur Herzog, Jr., and recorded by Holiday in 1941. But this caused me some consternation. It seemed shocking that anyone but Holiday (or Diana Ross as Holiday) would dare to sing this number, let alone Eydie Gormé (known mostly to me at that time as the singer of the peppy novelty “Blame It on the Bossa Nova”). But I couldn’t help it: I truly liked the Eydie version, middle-of-the-road and “white bread” though it might be. I guessed I was hopelessly square.

Looking back at Since I Fell for You with more perspective, I find I still like the album. A lot. Yes, it’s very string-heavy throughout. The violins sweep in, sometimes to fine, rich effect, but elsewhere unnecessarily. They surge like a warm, engulfing wave of Mrs. Butterworth’s syrup on some numbers. These arrangements remind me of early 1960s “easy listening” pop songs I remember hearing during early childhood, from singers like Johnny Mathis and Nat King Cole, on radio station KEX in Portland. Lots of goopy strings were part of the deal.

Also, the album gets off to a bad start by presenting two songs with similar structures and very similar approaches: the album’s title tune (written by Buddy Johnson) and “Breakin’ Up Is Hard to Do” (Neil Sedaka, Howard Greenfield). What were Don Costa and company thinking when they ordered the selections?

On the other hand, Eydie is in glorious voice throughout these 10 tracks. Like my cherished Barbra Streisand, she tends to start a song small and then crescendo to a blazing belt. But Gormé’s volume control is very finely tuned, and she uses it here in surprising ways. On Irving Berlin’s “What’ll I Do,” for instance, she sings the introductory verse fairly loud, then grows quiet for the main melody. In her bluesy take on Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight” (with a blessedly string-subdued arrangement), she recognizes that this is a kind of nocturne and basically whispers much of the song. She does tease us with a few more vehement notes in the bridge, and it seems as though she’s going to pump up the volume as usual. But she doesn’t. The track ends with a quiet, ridiculously prolonged, almost supernaturally sustained note that is given a fade-out before Eydie bothers to stop singing. You wonder: Could she still be holding that note somewhere even now—her vibrato fluttering here and again as if to prove that the sound is human and not celestial? Listen HERE.

Gormé’s startling five-octave vocal range (demonstrated so dramatically HERE, at the end of her video performance—circa 1957—of Oscar Hammerstein and Ben Oakland’s “I’ll Take Romance”) is also on display, as when her takes a big leap up near the end of “Come in from the Rain” (Melissa Manchester, Carole Bayer Sager).

As for “God Bless the Child,” I think I was right about it. Whether or not you think Eydie had the cred to sing the number, her interpretation is irreproachable. She starts it simply and with a plain, unwavering, youthful-sounding voice. She flames up on the bridge, but whenever she comes to the words “Mama may have, Papa may have,” her voice turns quiet and child-like again. But then, my God, her vibrato as she sings the final note is a thing of beauty and—thanks to today’s music-streaming platforms—a joy forever as well. Listen to the track HERE.

While I’m glad I revisited all three of these albums, the one I imagine I’ll turn to again and again is Since I Fell for You. It shows an abundantly gifted singer in full command of her artistry.

And, unlike the other two albums, this one seems…less dated somehow. Maybe—the Muzak-ish strings notwithstanding—one could make the case that it’s just plain timeless.

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.