Cabaret Setlist: “Sleigh Ride in July” (Music by Jimmy Van Heusen, Lyrics by Johnny Burke) and “Winter of My Discontent” (Music by Alec Wilder, Lyrics by Ben Ross Berenberg)

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Selection #11 in this running series.

There’s nothing like mixing things up a little.

The format of today’s “Cabaret Setlist” differs somewhat from previous installments. Up until now, we’ve looked at specific songs and the ways in which singers have made them their own. Today, we’ll check in with a cabaret performer who chose two songs (both relatively obscure) and paired them to make a specific point in a show with an overarching theme.

Andrea Axelrod is a cabaret singer with operatic training. According to her online bio, that background has qualified her to “kiss, kill and seek revenge in at least five languages.” She also has a degree in journalism, and she loves to research things.

Andrea Axelrod is a cabaret singer with operatic training. According to her online bio, that background has qualified her to “kiss, kill and seek revenge in at least five languages.” She also has a degree in journalism, and she loves to research things.

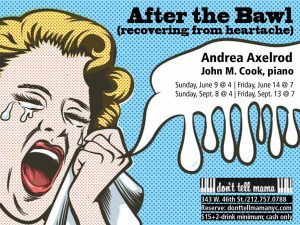

Some years ago, she decided to create and perform a trilogy of cabaret shows about aspects of love. The first, Almost Like Being in Love (songs on the cusp of love), was presented at the Metropolitan Room in 2016. It was about the illusions people harbor about love, or—as Lorenz Hart puts it—“the self-deception that believes the lie.” She followed that show with After the Bawl (recovering from heartache) in 2019, at Don’t Tell Mama. In this one, she performed the two songs we’ll look at here. (Axelrod says she may scrap the idea for the third planned program, which would have featured songs about being wildly, madly in love.)

Surviving Splits-ville

Both of the songs Axelrod chose for this part of her show deal with the flood of emotions that come at the end of a love affair. But these numbers have quite different pedigrees.

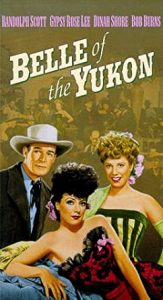

Composer Jimmy Van Heusen and lyricist Johnny Burke wrote “Sleigh Ride in July” for the film Belle of the Yukon, a 1944 quasi-musical starring Gypsy Rose Lee, Randolph Scott, Dinah Shore, and Bob Burns. Shore plays the daughter of a dance hall manager. She sings this number early in the film, after coming to believe she’s been snowed by her beau. She performs the song for the saloon patrons as she fights back tears of despair.

Composer Jimmy Van Heusen and lyricist Johnny Burke wrote “Sleigh Ride in July” for the film Belle of the Yukon, a 1944 quasi-musical starring Gypsy Rose Lee, Randolph Scott, Dinah Shore, and Bob Burns. Shore plays the daughter of a dance hall manager. She sings this number early in the film, after coming to believe she’s been snowed by her beau. She performs the song for the saloon patrons as she fights back tears of despair.

This is not a song one hears often in cabaret shows. Singer Jeff Macauley prepared his own version of it for his 1997 tribute show, MWAH! The Dinah Shore Show (revived in 2016), but the number was eventually cut from the setlist, as was a somewhat better-known Van Heusen / Burke song from Belle: “Like Someone in Love,” which, over the years, has become something of a jazz standard.

“It’s a weird movie,” says Macauley of Belle. “Dinah is way too old to be the naïve daughter. She was 28 when she filmed it, which makes her about 90 in ingenue years in ‘40s Hollywood.”

He appreciates Shore’s take on the song. “[It’s] presented first as a teary confessional and then a rousing ‘get yourself together, girl’ sing-along. I think she does particularly well, and I like how it’s staged, with Dinah getting a boost from Gypsy in the wings before [Gypsy] pushes her back out for the encore. It seems like this was staged to be Dinah’s big showcase in the film.”

Macauley notes that “Sleigh Ride in July” became a “minor hit” on the pop charts for both Shore and Bing Crosby. But perhaps its peculiar lyric, which makes it seem (and yet not seem) to have a Christmas-y connotation, may have quashed its potential to become a true classic. The song may not even make total sense in the context of Belle of the Yukon. As Macauley points out, “The Yukon might be the only place that you could actually go for a sleigh ride in July.”

The song has been covered by a few other vocalists, including ever-sultry Julie London, who performed it on her 1960 album Calendar Girl, on which each song celebrates a different month of the year. A bit of “Jingle Bells” can be heard at the very end, though the song represents a midsummer month on the album.

Lena Horne also recorded the number, for her 1959 collection of Van Heusen and Burke titles. Her track has been presented in a Christmas context also (see clip below), although she did not include it on her 1966 holiday album, Merry from Lena.

Axelrod was drawn to the song after a chat with Macauley. She finds its melody appealing. Granted, it’s “semi-obscure,” she says, “but it’s such a Tin Pan Alley song, you wonder why it isn’t a standard. It sounds like a standard. It sounds lush and…pretty, and [the character] is saying what she has to say to a nice tune.”

On the other hand, there’s “Winter of My Discontent.” With a title that calls to mind the opening line of Shakespeare’s Richard III—not to mention John Steinbeck’s final novel—the song announces itself at the outset as something more than a cute little ditty. Toronto bassist Steve Wallace—who recently included Helen Merrill’s rendition in a playlist celebrating “the joys of winter”—describes it as “moody and stark.” (Each of us finds “joy” in different places, it seems.)

For a gent’s take on the song, here’s Anthony Newley’s 1964 rendition:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65OVvBprxP0

Alec Wilder teamed with lyricist Ben Ross Berenberg to write this sturm und drang-y ballad, which was first recorded by Shannon Bolin in 1955. Listen here. I’m not sure exactly how the duo came to write the song. But they had collaborated in the  late 1940s on a children’s opera called The Churkendoose, which was based on the lyricist’s 1946 kids’ book of the same name. (This opera—about a hybrid bird: part chicken, part turkey, part duck, part goose—made something of a hit when a recording was made, narrated by Ray Bolger.)

late 1940s on a children’s opera called The Churkendoose, which was based on the lyricist’s 1946 kids’ book of the same name. (This opera—about a hybrid bird: part chicken, part turkey, part duck, part goose—made something of a hit when a recording was made, narrated by Ray Bolger.)

Wilder is probably better known not as a composer but as the author of the 1972 volume American Popular Song (which I quoted a couple of weeks ago in my look at Rodgers & Hart’s “Mountain Greenery). In that book, according to writer Whitney Balliett, Wilder takes a stand against such elements as “melodrama” and “pretentiousness” in pop songs. But do he and Berenberg manage to avoid those very no-no’s in “Winter”? After all, this is a song about the end of an apparently brief (and presumably unconsummated) love affair, but the song’s despairing first-person protagonist makes it seem that the fate of civilization is on the line:

Now all the follies of the world seem small.

Let the empires rise and let the heroes fall.

And let the ruins burn, for there’s no love at all

In this winter of my discontent.

Of course, when you’re hit with a romantic break-up, the pain can land in a manner that feels apocalyptic. And Axelrod certainly kept that in mind when she decided to pair “Winter of My Discontent” with “Sleigh Ride in July.”

Secret Ingredients

Her goal with After the Bawl was to present a sort of musical version of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s “stages of grief,” but tailored specifically to the grief that comes at the end of a romance. She began her setlist with “I Had Myself a True Love” (Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer) and finished the evening with Rodgers & Hart’s “I Wish I Were in Love Again.” All the songs between these numbers were chosen to reflect the various stages of recovery from post-romantic grief.

“Everything was dictated by that arc,” she says. “The problem with that was that I was starting with the saddest of situations: with the true grief.” Axelrod’s musical director, John M. Cook, suggested Stephen Sondheim’s relatively lively “Now You Know” as a song to pair with “I Had Myself a True Love” (which Axelrod describes as “a real downer of a song—not what you usually start a show with”).

Just to clarify: Axelrod makes a distinction between “paired songs” and “mashups” (the latter of which are songs with intertwined components—such as in the famous Garland/Streisand duet that blends “Get Happy” and “Happy Days Are Here Again.”) It seems that, for vocalists performing live, the term “mashup” (which, apparently, was first used to describe an overlay of songs done in the recording studio) has become nearly synonymous with the term “medley.” In contrast, “paired songs” are presented sequentially but without a break for applause. Axelrod was especially comfortable with this practice because of her classical training. (German lieder, she observes, are traditionally presented in this way, with applause coming only at the end of a set, preventing interruption of the dramatic or thematic progression.)

The first five songs in Axelrod’s set comprised a sort of first act or first movement of her show. Seeking a way to unify these musical numbers, she came upon an analogous situation from television’s cooking show Iron Chef. On that program, contestants are asked to incorporate a “secret ingredient” into each course of a five-course meal.

“I realized that I was trying to incorporate grief and sadness and despair into five songs. The secret ingredient was in each of the songs, but it had to shine in a different way…otherwise the audience would have been just bereft and miserable.”

The Arlen/Mercer and Sondheim pairing that opened the show included a shift in mood between songs, but both selections, says Axelrod, made the same basic point: “I’ve been deserted, and it ain’t fair.”

For the third and fourth songs in her show, we arrive at the “Sleigh Ride in July”/ ”Winter of My Discontent” pairing. Here’s a video of the entire sequence, beginning with the patter that leads into the two paired songs.

The point Axelrod wanted to illustrate in this pairing of what Axelrod calls “scenes” had to do with the pervasiveness of heartbreak. In the spoken narration (patter) preceding the number, she talks about how the devastation following a breakup can strike at any time of year: “Every season is an equal opportunity for self-pity, lamentation, and blubbering.”

As you can tell from that line, Axelrod here is leavening the heavy stuff in her show with humor. This culminates in her broadly funny anecdote about singing “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” in a German rathskeller, which helps set the audience up for the relatively light “Sleigh Ride in July.”

Granted, the song may regard romantic failure a bit more seriously than Axelrod’s introductory patter. But it continues to treat the subject rather breezily. The protagonist in the song is bemused but not destroyed by the breakup (the sensibility here is a bit like Dinah Shore’s after Gypsy Rose Lee pushes her back onto the dancehall stage). “I think she’s sort of just shrugging her shoulders: ‘I got taken. It isn’t winter.’ And then—suddenly—’Winter’ does come.”

The notes in the first song are fairly low, which Axelrod believes helps makes the song somewhat conversational. And when she segues into the second song, she begins it a full octave lower than written, so that it sounds “as if it came out of the same ‘pot of goodness’ as ‘Sleigh Ride.’” But then, in the middle of the lyric “like a dream he came, and like a dream he went” she shifts up to the higher octave and into a higher emotional pitch in the bargain. She wanted a deliberately “overwrought” effect during the bulk of the Wilder/Berenberg song.

“You know, we self-dramatize when our hearts get broken,” she says. “I wanted it to have that kind of ‘sob’: ‘Let the empires rise, let the heroes fall….’ I thought it was OK not to oversing it, but to sing it with the ammunition I had.”

In patter that appears after the song ends, Axelrod switches the mood yet again. She takes us out of the realm of bombastic self-pity by exaggeratedly and humorously boo-hooing to mime her own overwrought reaction. It’s not that she is necessarily belittling the genuine angst that emerged in the course of her performance of “Winter.” Instead, she puts the devastation in a healthful sort of perspective. She’s moving us forward through the Kübler-Ross-like stages.

On a more technical and practical level, Axelrod saw a further advantage in pairing these songs. Both are relatively abbreviated. “Sleigh Ride” has a very short verse, and the chorus has no bridge. “Winter” has no verse, just a chorus. Putting the two songs together creates a fuller, more expansive experience for the listener. It was musical director Cook’s idea to link the songs with quotations from “Jingle Bells”—in a major key after “Sleigh Ride” and a minor key following “Winter.” This is reminiscent of what Julie London’s arranger had done on her recording of “Sleigh Ride.”

The fifth and last song in Axelrod’s opening sequence marks yet another a step forward in the journey out of heartache. It’s “I’m Thru with Love” (Gus Kahn, Matt Malneck, Fud Livingston).

If you wish to witness all the stages of lost-love grief that Axelrod explored, you can watch the entire After the Bawl show here:

Together for the First Time

Axelrod finds the process of researching and putting together shows to be even more fulfilling than performing them. And she finds song-pairing—along with the “mashing-up” of songs—to be a special pleasure.

She recalls that, back in the days when she worked with the late musical director Paul Trueblood, she had great fun finding songs that meshed well. One of her all-time favorites was an intertwining of Rodgers & Hart’s “The Blue Room” and Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” Not only were the structures and harmonies of the songs perfect matches, but the songs also shared an almost identical lyrical idea: the desire to arrange a cozy love nest. “It’s almost as if Lerner & Loewe said, ‘Let’s put together a “Blue Room” song.’”

But not all of her melodic matchmaking adventures have worked out. Axelrod once attempted to pair two Lerner & Loewe songs: “Why Can’t the English?” (from My Fair Lady) and “The Parisians” (from Gigi). “I tried it in a workshop with Peter Napolitano and Matthew Martin Ward, and they appropriately ixnayed it. Both songs were teasing about national character (as only Alan Jay Lerner could), but the wit and wisdom of each wasn’t strengthened by putting them together. And adding the weaker song (“Parisians”) to such a fabulous list song took away from the latter.”

She advises her fellow cabaret singers to pair songs only when they truly need to be together.

“There really has to be a reason. Sometimes—and God knows I’m sometimes guilty of this—you can be so clever that only you can understand the reason you’re pairing them.”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.