Cabaret Setlist: Springing Forward with Three Songs of Hope and Happiness

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Article #14 in this ongoing series

In the most recent installments of “Cabaret Setlist,” we’ve looked at the brilliant-but-dark “Lush Life” and the splendid-but sad “When October Goes.” I love these musical explorations of anguish and heartbreak, but I realize they’re not the only sorts of songs worth singing.

So, enough already! Spring is here, COVID-19 vaccines are a-flowin’, and the 36th Annual Bistro Awards show is set for April 30. Time for some upbeat song selections? I should say so.

Today, instead of examining a single song, I’d like to take a look at three pieces, each of which I would welcome hearing live once cabaret clubs begin reopening in 2021. (And they will reopen, dammit.) The first two are songs that I don’t ever recall having encountered on a cabaret setlist but that would be most welcome additions. The third is somewhat better known by cabaret-goers, though not as widely heard as, say, “Besamé Mucho” or “Here’s to Life.”

“How Much of the Dream Comes True” – Music by John Barry, Lyrics by Trevor Peacock (1965)

If we were to get all technical, this charming little “wanting song” might not be classified as part of the American Songbook at all. It was born in the U.K.—specifically in a West End musical that didn’t transfer to Broadway. But wait. American cabaret has welcomed contributions from such songwriters as Ivor Novello, Noël Coward, Leslie Bricusse, Anthony Newley, the Beatles, Andrew Lloyd Weber, and Adele. So, let’s not get all technical.

The show that brought us “How Much of the Dream Comes True” was The Passion Flower Hotel, based on a novel of the same name by Rosalind Erskine (a pen name of novelist Roger Erskine Longrigg). The libretto might not pass muster with social critics these days. On the other hand, it might be embraced by sex-positive capitalists. It’s the story of young women in a boarding school who decide that, in order to lose their virginity, they’ll open a brothel that will attract males from another nearby school. The principal female character, portrayed in 1965 by Francesca Annis, sings this winsome ballad.

The music was composed by John Barry—who would famously write the musical scores for many James Bond films. He would also wind up winning five Academy Awards (all for non-Bond-ers). Barry crafted a simple but quite enticing melody for this ballad. Lyricist Trevor Peacock relies on a series of bold statements about the romantic happiness the protagonist longs for, each of which is quickly followed by a qualifier that throws doubt on that momentary optimism:

There will be violins playing

Softly, somewhere, won’t there?

I shall be flying through rainbows

Though I can’t fly, shan’t I?

In short, the character is in a debate with herself, which gives the singer something dramatic to work with.

A cast album was made of this show’s score, but I could not find a version of Annis singing the number anywhere online. In fact, the principal reason why anyone recalls this song is an appealing recording made in 1965 by Barbra Streisand—and it’s certainly not one of the more conspicuous entries in her catalog. She included it on her album My Name Is Barbra, Two, which was partly a soundtrack from her first, groundbreaking CBS television special. (This song was not heard in the special, however—only on the album.) Incidentally, as Matt Howe of the invaluable Barbra Streisand Archives website points out, soon after The Passion Flower Hotel closed at the Prince of Wales Theatre, Streisand opened at the same venue with the London run of Funny Girl (1966). The singer also released a “How Much of the Dream Comes True” single, backed by a rendition of “Autumn” (by 2020 Bistro Awards Lifetime Achievement honorees Richard Maltby and David Shire).

A cast album was made of this show’s score, but I could not find a version of Annis singing the number anywhere online. In fact, the principal reason why anyone recalls this song is an appealing recording made in 1965 by Barbra Streisand—and it’s certainly not one of the more conspicuous entries in her catalog. She included it on her album My Name Is Barbra, Two, which was partly a soundtrack from her first, groundbreaking CBS television special. (This song was not heard in the special, however—only on the album.) Incidentally, as Matt Howe of the invaluable Barbra Streisand Archives website points out, soon after The Passion Flower Hotel closed at the Prince of Wales Theatre, Streisand opened at the same venue with the London run of Funny Girl (1966). The singer also released a “How Much of the Dream Comes True” single, backed by a rendition of “Autumn” (by 2020 Bistro Awards Lifetime Achievement honorees Richard Maltby and David Shire).

Don Costa arranged the Streisand version of this song, which lilts and twinkles along at a nice mid-tempo pace. The singer shows a restraint here that fits the song nicely. There are none of the big, larynx-challenging climaxes in this performance that occur on many an early Streisand track. At the very end of the number, Costa includes a sort of echo effect, in which he has the orchestra twice repeat the last plaintive notes that Streisand has just sung. Click here for Streisand’s version.

For me, the big mystery here is why no other vocalists seem to have had a go at recording this song. The only other version of it readily available online—by the Mike Sammes Singers—is one of those easy-listening choral renditions that proliferated in the 1960s. This ensemble is a mixed group of female and male voices, singing about a dream guy (though the women’s voices do predominate on some of the more intimate lyrics about getting amorous with the fella). Sample the Mike Sammes Singers’ rendition.

For me, the big mystery here is why no other vocalists seem to have had a go at recording this song. The only other version of it readily available online—by the Mike Sammes Singers—is one of those easy-listening choral renditions that proliferated in the 1960s. This ensemble is a mixed group of female and male voices, singing about a dream guy (though the women’s voices do predominate on some of the more intimate lyrics about getting amorous with the fella). Sample the Mike Sammes Singers’ rendition.

These days, some female cabaret performers, as well as many a male singer, might make good use of this number without changing the original pronouns.

Besides, who wouldn’t be happy to sing a song containing the phrase “shan’t I?”?

“A Natural Man” – Music and lyrics by Sandy Baron and Bobby Hebb (1971)

“It’s a new day, babies!”

We’ve now had a year plus change of masking up, maintaining social distancing, and drenching our palms in Purell (and thanks, everyone, for doing all that). This classic R&B hit with its kicky rhythms and smooth background vocals will certainly speak to anyone who’s good and ready for liberation from such restraints and precautions. “A Natural Man” has not been much of a cabaret staple, but now might be its time. Well, soon anyway.

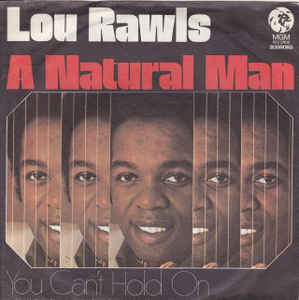

R&B star Lou Rawls won a Grammy award for his recording of this energetic number. “A Natural Man” was written by Sandy Baron (the comedian and actor who would go on to play a recurring role on Seinfeld) and Bobby Hebb (whose other major hit was 1963’s “Sunny,” as in “Sunny, one so true—I love you”). I’m not sure exactly how the two songwriters found each other, but Baron had had considerable earlier experience making records, having taped comedy albums of his nightclub acts. He’d also made some musical novelty singles with Joan Rivers early in the 1960s. The straight comic would eventually go on to record a pro-gay comedy album called God Save the Queens (1972). You can find it online, but—warning!—what passed for “pro-gay” content in 1972 isn’t exactly woke today.

R&B star Lou Rawls won a Grammy award for his recording of this energetic number. “A Natural Man” was written by Sandy Baron (the comedian and actor who would go on to play a recurring role on Seinfeld) and Bobby Hebb (whose other major hit was 1963’s “Sunny,” as in “Sunny, one so true—I love you”). I’m not sure exactly how the two songwriters found each other, but Baron had had considerable earlier experience making records, having taped comedy albums of his nightclub acts. He’d also made some musical novelty singles with Joan Rivers early in the 1960s. The straight comic would eventually go on to record a pro-gay comedy album called God Save the Queens (1972). You can find it online, but—warning!—what passed for “pro-gay” content in 1972 isn’t exactly woke today.

Rawls recorded “A Natural Man” as the centerpiece of the first album he made following his move from Capitol Records to the MGM label. The track has a fairly long spoken introductory passage that ruminates on how folks aren’t putting up with being pushed around as they were back in the bad old days. The song not only reflects Civil Rights concerns of the early 1970s (and—sad to say–of the early 2020s) but also speaks for pretty much anyone who has grown weary of saying, “Yes, of course” when the real answer is, “No, now buzz off, please.” I imagine that the Rawls spoken passage would be scrapped in most cabaret performances now—or, perhaps better, retooled to express the agenda of the singer who sings it. Listen to Rawls here.

By the way, inclusion of spoken monologues in R&B recordings a half century ago was not at all unusual. Perhaps Diana Ross’s “If you need me, call me…” intro to “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” is the most famous example. In a way, the mixture of spoken word and sung lyric underscores such songs’ theatricality. Just as in musical theatre, it often makes sense in pop songs to utilize spoken text before finding it necessary to burst into song. (Not all spoken passages in R&B songs, by the way, happen at the beginning of the performance.)

“A Natural Man”—like “How Much of the Dream Comes True”—has had a surprisingly lean history as far as covers are concerned. In 1974, however, Liza Minnelli (later, a Bistro Awards honoree) recorded the number in a rendition heard on her Live at the Winter Garden album. This performance was recorded in January of that year, and the album was released only three months later. Minnelli—who celebrated her 75th birthday earlier this month—was, during that period, at the height of her popularity. She was still on that wild success streak that included Cabaret on film and Liza with a Z on television. Bob Fosse, who had directed both of those projects, helmed her Winter Garden show as well.

“A Natural Man”—like “How Much of the Dream Comes True”—has had a surprisingly lean history as far as covers are concerned. In 1974, however, Liza Minnelli (later, a Bistro Awards honoree) recorded the number in a rendition heard on her Live at the Winter Garden album. This performance was recorded in January of that year, and the album was released only three months later. Minnelli—who celebrated her 75th birthday earlier this month—was, during that period, at the height of her popularity. She was still on that wild success streak that included Cabaret on film and Liza with a Z on television. Bob Fosse, who had directed both of those projects, helmed her Winter Garden show as well.

Minnelli’s version of “A Natural Man”—not unexpectedly— became a production number with some strenuous dance moves. Anyone thinking about performing this number should definitely be prepared to do something more than stand stock-still. Watch Liza here.

Those who were around in the early 1970s will likely recognize in Minnelli’s rendition an interpolated musical theme: the once ubiquitous “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby” jingle from the old Virginia Slims TV campaign. Yes, cigarette ads were once as prevalent on television as big-pharma spots for diabetes meds and psoriasis treatments are now.

Note that Minnelli alters the song’s words so that her character wants not to be a natural man but to have a natural man. This changes the slant of the song altogether. It’s no longer about personal liberation as when Rawls sang it. Instead, it’s about sexual desire and romantic fulfillment. It’s still a driving, buoyant, exuberant song, yet it’s somehow not the same song at all.

“Poor Everybody Else” – Music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by Dorothy Fields (1965)

There may be a sort of logical progression with the three songs we’re examining here. “How Much of the Dream Comes True” is a song of hope, tempered by doubt. “A Natural Man” is a suave anthem full of cocky defiance in the face of doors slammed shut. “Poor Everybody Else” is one of those roaring musical-theatre arias that enlists sheer force of will in order to unilaterally declare victory over bum times.

In short, it’s a song that dromps.

Here’s what I mean. A “dromping” song is what I call one of those unrestrainedly determined songs—often (but not always) from musical theatre of the mid-20th century—with a pulsing energy that cannot be extinguished, curbed, or tuned out. Think of “Everything’s Coming Up Roses” from Gypsy, “Nothing Can Stop Me Now” from The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd, “You’re Gonna Hear from Me” from the film Inside Daisy Clover, and “But Alive” from Applause. The quintessential song of this sort, however, has got to be Funny Girl’s “Don’t Rain on My Parade” (Jule Styne, Bob Merrill).

When writing about that song at some point, I used the acronym “DROMP,” which can be lowercased and utilized as a crisp action verb. Thusly:

Dromp (vt, vi dromped, dromping): To sing like bloody hell in order to turn one’s situation around. (“I boarded that tugboat with my arms full of yellow roses and proceeded to dromp my way into Nick Arnstein’s arms.”)

“Poor Everybody Else” is a brilliant dromper. But it is a song that narrowly escaped obscurity. It was originally written by Cy Coleman and Dorothy Fields for 1966’s Sweet Charity, in which it would have been sung by heroine Charity Hope Valentine. But the song was cut from that show. Perhaps—considering the inclusion of the similarly upbeat “I’m a Brass Band”—it was considered redundant.

But the song worked well in 1973 when given to Gittel Mosca in the musical Seesaw (adapted from the 1958 play Two for the Seesaw by William Gibson, and written, directed. and choreographed by Michael Bennett). Gittel’s romantic woes are not so different from Charity’s, after all. “Poor Everybody Else” was performed passionately in Seesaw by Michele Lee. (I was lucky to hear Lucie Arnaz sing it in the show’s 1974 national tour, as well as in her 2018 show at the Birdland Theatre). Coleman’s driving melody, orchestrated for Seesaw by Larry Fallon, is a burst of melodic and rhythmic excitement, while Fields’s lyrical hook deftly helps define the character who sings the number.

But the song worked well in 1973 when given to Gittel Mosca in the musical Seesaw (adapted from the 1958 play Two for the Seesaw by William Gibson, and written, directed. and choreographed by Michael Bennett). Gittel’s romantic woes are not so different from Charity’s, after all. “Poor Everybody Else” was performed passionately in Seesaw by Michele Lee. (I was lucky to hear Lucie Arnaz sing it in the show’s 1974 national tour, as well as in her 2018 show at the Birdland Theatre). Coleman’s driving melody, orchestrated for Seesaw by Larry Fallon, is a burst of melodic and rhythmic excitement, while Fields’s lyrical hook deftly helps define the character who sings the number.

Gittel is one of those doubt-filled sorts whose neuroses prevent her from striding down that sunny side of the street once famously heralded by Dorothy Fields. The character is the embodiment of self-deprecation. As she puts it in an earlier number in the show: “If there’s a problem, I duck it. / I don’t solve it. I just muck it up.” (Certainly, the use of “muck it” here was a bowdlerized substitution.) In “Poor Everybody Else,” the pessimistic gremlin in Gittel’s psyche won’t allow her to see the world as a completely joyful place, so she frames her own sudden happiness in contrast with the relative unhappiness of others: “I’m sorry they’re not loved / Like I’m being loved.” The song poses as a message of sympathy for others, but it’s actually ecstatic fanfare for self. Hear Lee belt out this song here.

Having decided to write about this song, I reached out to Michele Lee, who very kindly agreed to answer some of my questions about it. She noted that when she was hired to play Gittel during pre-Broadway tryouts, the number was already in the show. Singing an interpolated trunk song from Sweet Charity didn’t bother the star. “Charity is Gittel is Charity is Gittel,” she says. “They are basically the same woman learning how to love herself.”

In Seesaw, the song was reprised in the production number “Chapter 54, Number 1909,” in which Gittel’s pal David (Tommy Tune) teaches her boyfriend, Jerry (Ken Howard on Broadway, John Gavin in the touring company), how to memorize legal statutes by tap-dancing to them. This gave theatergoers a double dose of production-number energy. Lee doesn’t recall exactly when “Chapter 54” was added to the show, but she remembers being called to rehearsals for it, along with Tune.

“What I do remember [is that] the reprising of ‘Poor Everybody Else’ as part of Chapter 54, Number 1909” was beyond thrilling for me as an actress with deep admiration for the complexity of Cy Coleman’s work. As she watches Jerry learning statutes for his bar exam, Gittel knows he’ll stay with her, and sings ‘Poor Everybody Else.’ Even though [cabaret] performers wouldn’t have the ability to sing this while tapping, they have to hear the brilliance of Cy Coleman and Dorothy Fields.” Here’s “Chapter 54, Number 1909” from Seesaw.

The song did provide some vocal difficulties for Lee: “’Poor Everybody Else’ was difficult to sing because it sat in the ‘break’ of my voice and was vocally tiring.” Still, it was a rewarding number to perform. “With all the loss in her life, it was important to see Gittel finally win. I loved it.’” (Note: The show’s closing scenes are not nearly so rosy, but they provided Lee with a strong ballad in a torchy song called “I’m Way Ahead.”)

Listening again to the cast album (a vinyl version of which I wore out in the 1970s), I wonder why the Seesaw score doesn’t have a stronger reputation and why the musical has never had a full-scale Broadway revival. (An Off-Broadway version had a brief run on Theatre Row in 2020, shortly before the onset of the pandemic.) In addition to “Poor Everybody Else” and “I’m Way Ahead,” Seesaw offered two other memorable numbers: Gittel’s slightly bawdy novelty song, “Welcome to Holiday Inn.” and David’s spunky “It’s Not Where You Start.” They’re fair game for cabaret performers also.

Listening again to the cast album (a vinyl version of which I wore out in the 1970s), I wonder why the Seesaw score doesn’t have a stronger reputation and why the musical has never had a full-scale Broadway revival. (An Off-Broadway version had a brief run on Theatre Row in 2020, shortly before the onset of the pandemic.) In addition to “Poor Everybody Else” and “I’m Way Ahead,” Seesaw offered two other memorable numbers: Gittel’s slightly bawdy novelty song, “Welcome to Holiday Inn.” and David’s spunky “It’s Not Where You Start.” They’re fair game for cabaret performers also.

Unlike the two other songs spotlighted in this article, “Poor Everybody Else” has had a fairly rich life apart from the two musicals it’s associated with. Sylvia Syms actually recorded a raucous and likable version of it at the time Sweet Charity opened—long before Lee would sing it on the Seesaw cast album. Relish listening to Syms’ audio of it.

Marilyn Volpe performed a crackerjack version with a jittery piano (arrangement and accompaniment by the late Wes McAfee) in a live recording taped at Tavern on the Green (1996): Listen here.

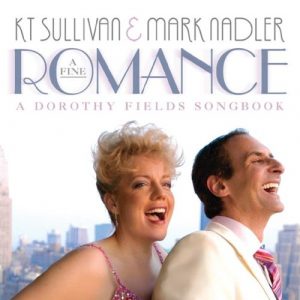

KT Sullivan and Mark Nadler slowed the song, transforming it into a charming ballad for their 2006 recording A Fine Romance: A Dorothy Fields Songbook. Notes Nadler: “I thought it would serve the lyric better to have [Sullivan] ‘languish’ in the joy of being in love rather than blaring about it.” This dreamily lush rendition is a testament to the principle that songs can adopt appealing new guises when artists are willing to take big chances with them: Experience it yourselves.

KT Sullivan and Mark Nadler slowed the song, transforming it into a charming ballad for their 2006 recording A Fine Romance: A Dorothy Fields Songbook. Notes Nadler: “I thought it would serve the lyric better to have [Sullivan] ‘languish’ in the joy of being in love rather than blaring about it.” This dreamily lush rendition is a testament to the principle that songs can adopt appealing new guises when artists are willing to take big chances with them: Experience it yourselves.

I’ll give the last word to Lee, who revisited the number in a Cy Coleman tribute show at Feinstein’s 54 Below a few years ago: “This song is a showstopper. The vocal and orchestration grow in intensity, which exudes so much joy. And as a matter of advice, I say, ‘SING JOY!’”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.

I have a copy of the original cast album of The Passion Flower Hotel, in the event you ever want to hear the Annis version of “How Much of the Dream Comes True.” And, Mark, I’ve really been enjoying this Cabaret Setlist series you’ve been writing!

Thanks, Lisa Jo –

Would be great to hear that song from “Passion Flower Hotel” sometime.

I’m glad you’ve enjoyed the “setlist” articles. I’ve greatly enjoyed researching and writing them!

Take care,

Mark