Changing Their Tunes…or Not: Cabaret Songwriters Adapt in a Volatile World

All sorts of people in cabaret circles can put “songwriter” on their résumés: singer-songwriters in the tradition of James Taylor and Joni Mitchell; cabaret artists who long to write songs for musical theatre; the musical director who occasionally creates “special material” for singing clients.

But, often, crafting songs is just one of such a cabaret artist’s many career skills.

Recently, I spoke with four people who do a considerable amount of composing and/or lyric writing. They talked about the contours of their careers and about how they’ve adapted their ways of working in order to keep the music playing in a world full of change. Here ‘s what they told me:

Songs as Stories: Amanda McBroom

Perhaps the biggest change in Amanda McBroom’s career as a composer and lyricist is that songwriting became —almost overnight—the most celebrated component of her overall artistry. When she started out as an entertainer, she didn’t write music at all. She was making a name for herself as an actress and a singer.

She began singing in her teens, performing the folk-y music of her role models, Judy Collins and Joan Baez, at fairs and other public events. It never occurred to her then to write her own material. Later, she appeared in a series of productions of the acclaimed revue Jacques Brel Is Alive and Living in Paris. Her husband, George Ball, was also in the Brel cast.

“He was working one night, and I was off, because nobody was allowed to do more than six shows a week because the show was so stressful on the vocal cords…. And I just picked up my guitar and something came out. He came back, and I said, ‘I don’t know what this is.’

“He said, ‘Oh, my God, you just wrote a song—and it’s good!’”

After that, she enjoyed “noodling around” with melodies and lyrics. It was “just a little hobby on the side.”

Her songwriting endeavors became more important once she began collaborating with singer/writer Michele Brourman. But the material McBroom wrote—both on her own and with her new partner—was material meant for her own sets. To this day, she has not actively marketed her songs to other singers.

Well, there was that one time—the time when fate stepped in and changed McBroom’s whole life….

At Brourman’s urging, McBroom’s submitted her ballad “The Rose” for consideration as the title song for the 1979 motion picture set to star Bette Midler (her first major role in a feature film). Although producers of The Rose disliked the song, Midler loved it. And Midler carried the day. “The Rose” went on to win a Golden Globe award and lodged itself in the ears of the masses.

It also opened doors. In subsequent years, everyone from Barbara Cook to Conway Twitty to Kurt Kobain recorded songs from the McBroom catalogue, which includes such titles as “Errol Flynn,” “Crimes of the Heart,” and “Wheels.” Listen to and watch Amanda McBroom sing “Wheels” HERE.

In a recent interview, McBroom told me that she continues to write in much the way she always has. Rhymes fly into her head all the time. She waits, though, until something—a sentence from an obituary, a line in someone else’s song—prompts inspiration and pulls her into work mode.

“I’m not a disciplined writer,” she says. “It happens when it happens. And it happens a lot less than it used to.”

McBroom writes both music and lyrics for some songs. More often, though, she works with a composer and writes lyrics only. Most often these days her collaborator is Brourman. Sometimes it’s Ann Hampton Callaway. The amount of collaborative output has grown over the years. She estimates that ninety percent of the songs she creates nowadays are team efforts.

Pop music has changed dramatically over the decades McBroom has been on the scene. Currently, the lyrical component of a song is one of the lesser things that writers, producers, and labels care about, she says. She notes that songs are now written “completely backward” from the way they used to be written.

“Unless you’re Taylor Swift or you’re in country [music], words are the least important part of the song. It’s [now] the groove, it’s the hook, it’s the drum track.”

She concedes that language and story are also still a component of hip-hop music (a genre she has not pursued). And, of course, having a coherent and purposeful lyric is still a factor in musical theatre composition. Nonetheless, times have changed.

“Songwriters are now having the most difficult time ever,” she says, “maybe since when they had to go out and hawk sheet music on the streetcorner in 1919 or something. It’s just so difficult to become supported by a label. You have to do so much on your own. And the ironic opposite of that is that if you do a TikTok video in your bedroom, you can become Justin Bieber. So, the opportunities have shifted in a whole other way. Studios are not looking for you anymore. You have to really, really push to have anybody discover you.”

McBroom has written for musical theatre, and she and Brourman have also had an extensive adjunct career writing songs for animated videos for children, most notably the Land Before Time series, which features speaking (and singing) dinosaurs. She finds writing for such projects much easier than writing “personal” songs meant for her own setlists. Essentially, these projects are a form of musical theatre, she contends—they’re reliant on situation and character.

“They’re not love songs, thank God,” she adds, “because it’s so hard to come up with a new love song. It’s been done! But a baby dinosaur singing about loving to dance in the mud? Thank you! You gave me the situation. I can go from there.”

The kinds of songs she’s created and to which she’s gravitated throughout her career—the early covers of songs by Collins and Baez, the numbers she performed in such musicals as Broadway’s Seesaw, intensely emotional ballads by Jacques Brel and Harry Chapin, anthems for determined young brontosauruses—all of these have one thing in common, she says: They’re songs that tell stories.

“I’m not a ‘hook-and-bridge dance-tune girl,” McBroom confirms. “I’m an ‘act one, act two, act three’ girl.”

Amanda McBroom next appears at the Purple Room in Palm Springs, CA, January 12 & 13, 2024.

On the Clock: Michael Holland

McBroom’s observations about the direction commercial pop music has taken are certainly not novel. But such trends can still strike a slightly sour chord for songwriters who came of age in the later-20th-century Singer-Songwriter era, when melody, rhyme, story, and literate lyrics were all still seen as valuable commodities.

Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, Michael Holland imagined himself squarely in that singer-songwriter category. He adored Joni Mitchell’s work and came to love the music of later artists, including Nick Kershaw and Andy Partridge. But his biggest influence, by far, was the rock group Queen. Hearing Freddy Mercury and company perform “Bohemian Rhapsody,” he quips, “ruined his life.”

“I didn’t know you were allowed to do that. That’s why I do what I do. It’s also why I don’t do [just] one thing. Because they were really versatile and sort of fearless, and they did a bunch of stuff they had no business doing.”

Queen proved to Holland that songwriters needn’t work within a single musical genre. And, indeed, Holland has taken inspiration from a disparate array of composers: Edvard Grieg, George Gershwin, Burt Bacharach, Jimmy Webb.

Holland studied music at the University of Connecticut, later transferring to Boston University. He honed his craft in Boston, his stay there providing “training wheels” for a career in New York, where he first landed in 1990.

“I did a few CDs—independent releases. I sold a few thousand CDs, which in the industry is nothing, but it is what it is.”

He believes that he came along, essentially, at “the end of the record industry.”

“It’s become such a small thing now,” he explains, in words that seem to echo McBroom’s: “There are a few artists that are massive, massive, massive. Then there are a million-million people out there just putting content out.”

When there are no songwriting projects on his plate, he does other work. He serves as musical director for cabaret shows and recordings. He and Karen Mack created and performed in the “alt-cabaret” Gashole! shows, which had a twelve-year run. He created orchestrations and vocal arrangements for the 2012 Broadway revival of Godspell, and he’s found work composing incidental music for nonmusical stage productions at theatre companies nationwide.

Increasingly, though, he works as a composer-lyricist for stage musicals. Last year, he supplied the score for an adaptation of Reginald Rose’s Twelve Angry Men for Theater Latté Da in Minneapolis. At the time I interviewed him for this article, he was juggling work for two other musicals: one for Latté Da (She’s Come Undone), the other in the U.K. (The Ghost and Mrs. Muir).

To a large degree, Holland is able to treat his songwriting work as a business these days. He notes that both She’s Come Undone and Mrs. Muir are projects he was hired to write.

“I’m able to clock in and clock out. In the old days, if an idea came to me on the street, I’d have to find a way to get it down so I didn’t forget it. Now, ideas don’t come to me on the street, because I’m not on duty. I clock in to do my work, and then I clock out.”

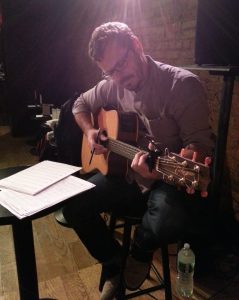

Watch and hear Holland play guitar as Lindsay Mendez performs one of his songs, “Howard Ate Thirteen Erasers,” HERE.

As a songwriter, he has not rejected all the technological advances that have turned the music industry inside out. But he balks at the current tendency to see producing, arranging, and songwriting as one simultaneous act of creation.

“I don’t think in ‘loops,’ because loops bore me,” he says. “Loops are the same chord, over and over and over again. You can make little adjustments and do fun little arrangement things, but that’s not how I write. I tried it…. It’s fun. It’s like a toy to me, but it’s not what I do. There’s not enough writing going on there for me. Which is another reason I like working in the theatre…. You don’t have to be stuck in a groove—or [in] just one little two-chord progression or riff or whatever.”

The act of creating a song never ceases to thrill him, even though he’s written, literally, a thousand songs.

“It’s that ‘where-there-never-was-a-hat’ thing,” he says, referencing Stephen Sondheim’s “Finishing the Hat.”

“It’s work, it’s hard. But when you’re done with it, there’s this thing, and you’ve made it. And it doesn’t come out of thin air—it comes out of all your experience and your education and your knowledge and your talent. And there’s some luck in there too. And I never get used to it! And every time it happens, I can’t believe it.”

Michael Holland’s songs and orchestrations for Twelve Angry Men: A New Musical will be heard again come springtime, when the show is staged at Asolo Repertory Theatre in Sarasota, FL.

A Passion for Creating: Tim Di Pasqua

As Tim Di Pasqua has matured as a musician and as a person, he’s found that his commitment to song creation remains as strong as ever. Even better, he’s been able to discard self-doubt and find new and more realistic ways of measuring success.

As a two-year-old in San Francisco, he began plunking out by ear some of the tunes he’d heard on television—the themes from Speed Racer and Batman. Meanwhile, another TV hero piqued the youngster’s interest in the American Songbook tradition: Bugs Bunny, singing of his passion for carrots in a parody of Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn’s “It’s Magic.”

But when Di Pasqua’s mother tried to teach young Tim to read music, it was a no-go. He could not absorb the idea of something as magical as music being represented “mathematically.” His parents hired another teacher for him, but he still couldn’t grasp the notation system.

“I would look at the page. As simplistic as it was, I wouldn’t be able to compute what the note was, what the value was. The instructor was really old school—literal ruler in hand. I would stumble while playing. He would get irate. He would play it, and then I’d play it back—because I’d heard what it sounded like. But I kind of phrased it in a way that it looked like I was interpreting it analytically.”

Despite his difficulty with staff lines and clef signs, he soon began playing his own melodies and writing his own rudimentary lyrics. He greatly enjoyed learning about rhyme schemes.

Eventually, he studied acting at San Francisco State University, appearing in a production of Side by Side by Sondheim. When the show moved to the Plush Room on Sutter Street, he followed—and earned his Equity card. At about this time, he also met his first significant romantic partner, Michael Levesque, who invited him to play piano for his cabaret show. Di Pasqua also helped Levesque’s best friend, singer-songwriter Tom Andersen, by “tuning up” melodies and creating arrangements for some of Andersen’s musical selections.

At this point, Di Pasqua had come to know much about what made a good pop song. He’d become serious about becoming a singer-songwriter.

“It wasn’t pastiche,” he says of his efforts at compostion from that period. “It was, ‘Oh, I see. There’s a template here, so let me see if maybe I can fit my own vision into this.’”

When Andersen—who’d moved to NYC with Levesque—booked an engagement at Carnegie Hall in 1993, he asked Di Pasqua to fly east to accompany him on piano. That night, Stephen Sondheim came backstage and complimented him on his arrangement for a Sondheim medley Andersen had sung.

That memorable encounter—no surprise—provided a big shot of encouragement. Soon, Di Pasqua joined his comrades permanently in New York, where he experienced “a tsunami of exposure.” He met people like composer Stephen Schwartz and ASCAP’s Michael Kerker. He returned to Carnegie Hall, this time to play for Michael Feinstein. He accompanied singers at Tavern on the Green and the Russian Tearoom.

He also continued writing, singing, and eventually recording his own music—and shopping songs to people like Anita Baker and Bette Midler. He and Levesque founded the Third Eye Theatre company and wrote a musical together, called, Synchronicity, which was recorded in 1998.

Through it all, however, Di Pasqua suffered from low self-esteem, something that would continue to dog him for years. Part of this was certainly connected to his lifetime difficulty with musical notations. He had found success as a musical director for some cabaret performers, but other singers seemed to avoid reaching out to him. Invited one year to sing at NYC’s Cabaret Convention, he performed a song of his from Synchonicity, along with his old Bugs Bunny favorite “It’s Magic.” But he was intimidated and discouraged by the presence of the founder and executive director of the Mabel Mercer Foundation, who—he felt—seemed to disapprove of his turn onstage.

Di Pasqua has lately gained much more self-assurance, in part by jettisoning unrealistic career expectations. He’s currently working on the development of two new stage musicals, and he continues singing and playing his own material.

“I’m not as hungry as I might have been in earlier days,” he says. “The passion for writing, for creating, and for exploring what’s inside of me—that’s increased. And it has, I think made a positive effect on the music I’m producing, both for the stage and…for my stand-alone songs.” His current outlook is best summarized, he says, in a song of his called “You.” Listen to him perform this very personal ballad HERE.

Unlike McBroom or Holland, he finds advances in music technology to be extremely beneficial in his songwriting life. Capitalizing on the digital music revolution, he’s been able to “flesh out every arrangement I was hearing in my head but wasn’t able to transcribe.” The Sibelius program allows him to print out the melodies he plays, with notations that can be shared with collaborators and fans. Meanwhile, his Instagram account and his channel on YouTube have made recordings of his songs (performed by himself and by others—notably, Stephen Schwartz and DeeDee Mango) available to an international community of music lovers.

He takes heart in hearing from listeners from around the globe who write to tell him how much a song of his has meant to them. His music, he says, has a life of its own, apart from him—and with no apparent expiration date.

“And that’s the real magic.”

Tim Di Pasqua will sing and play his music in a show called Story Hour at Manhattan’s Don’t Tell Mama, tentatively scheduled for November 18, 2023.

Old School, Fresh Sounds: Joe Iconis

These days, Joe Iconis tends to “go deeper” with songs than he did early on. When he was younger, he felt the need to write material that was “structurally sound and perfectly contained, from both a lyrical and musical perspective.” Now, he feels less need to prove himself to others. He’s more at ease with experimentation:

“I think I’ve allowed myself to get a little bit weirder with my songs.”

Iconis currently enjoys his status as one of theatre and cabaret’s most popular up-and-coming songwriters (he’s frequently a librettist, too). But he says that he’s, in fact, a very old-fashioned sort of composer-lyricist—insofar as he doesn’t bother with many 21st-century advances in music tech.

“I write at a piano with a pad,” he explains. “I don’t use any kind of software to write. I don’t do tracks. I don’t make demos. I really think that musical-theatre songs are ‘music and lyrics’ and that’s it. And I think that anything else is orchestration and arrangement, and that’s like a separate thing.”

In 2019, Iconis’s songs were heard on Broadway, in the musical Be More Chill, based on a novel by the late Ned Vizzini. It’s one of several musicals he’s scored, including his current show at California’s La Jolla Playhouse: The Untitled, Unauthorized Hunter S. Thompson Musical. Aside from his work in theatre, Iconis continues to play a role in cabaret, with the shows he presents in tandem with his coterie of loyal friends/collaborators, known as the “Joe Iconis Family.”

After completing an undergraduate degree in music composition and a master’s degree in musical theatre writing (both at New York University), Iconis was lucky to have a musical selected for development at a reputable theatre company. Being “in development” was, however, a frustratingly snail’s-pace experience. In the meantime, he felt the need to get his songs out and into the world. So, he began staging shows featuring Iconis Family members.

His cabaret cred is something he remains proud of—and something he claims has a lot to do with the success he’s found over the last 15 or so years. In fact, in our recent interview, he stated without equivocation: “Truly, everything in my career I can trace back to doing concerts at the Beechman.” (The Beechman is, of course, the Laurie Beechman Theatre in Hell’s Kitchen, one of Manhattan’s better-known cabaret venues.)

He notes that his song “Broadway Here I Come” was featured on NBC’s TV series Smash, because of a clip from a Beechman show viewed by the series’ showrunner, Joshua Safran. Also, the Hunter S. Thompson show at La Jolla was commissioned by theatre director Christopher Ashley, who’d seen a Beechman presentation featuring Iconis’s songs.

Originally from Long Island, Iconis developed a sudden interest in musical theatre as a kid, after seeing the original Off-Broadway production of Little Shop of Horrors. After that, he found a way to see whatever musicals he could find. He listened to cast albums. He learned all he could about the history of the musical stage.

“I would go see a show, and then I would come home and pick out the melodies that I heard—on piano. The more I developed that skill and…the knack for improvising, it sort of naturally turned into me writing my own songs.”

It wasn’t until his undergrad years that he began to feel comfortable writing lyrics. Then, in grad school, he “came into his own” both as a writer and “as a man.” He lost a good deal of weight, along with some heavy layers of social discomfort that had hampered him in his early years.

His way of creating a song has remained largely the same over the course of his career so far. His primary consideration is always the character who sings the number. And Iconis holds on to the homily that “content dictates form.”

“I’d like to think I’ve grown as a writer,” he says. “I don’t know if I’ve got better or worse. But I’ve certainly gotten different!”

He considers the stand-alone “cabaret” songs he writes to be as much “theatre songs” as the numbers he composes for musicals. Still, it’s mostly been only “theatre-adjacent” cabaret performers who’ve performed these stand-alones. While “Broadway Here I Come” and Be More Chill’s “Michael in the Bathroom” have had something of a life of their own, Iconis’s work has not yet been covered by major pop stars. Listen to and watch Will Roland sing “Michael in the Bathroom” HERE.

“If we were living in a different time, perhaps they would be crossover pop hits, in the way that [Louis Armstrong’s recording of] ‘Hello, Dolly!’ was. That’s just not the world we’re living in.”

And yet, like Tim Di Pasqua, Iconis is happy and thankful that social media and other online platforms have provided composers and lyricists with a vehicle for spreading the word about their songs, in much the same way radio play boosted the careers of theatrical songwriters in the mid 20th century.

“It’s just word of mouth,” he says of the proliferation of his music online. “It’s just people being turned on to the work and sharing material with friends. There’s no corporation that’s pushing it. It’s the material itself that’s speaking to people.”

This coming holiday season, the 13th Annual Joe Iconis Christmas Extravaganza, featuring members of the Iconis Family, will play at 54 Below (December 8 & 10, 2023.)

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.