One-Man-Show–manship: Lifetime Achievement Bistro Award Honoree Robert Klein on His Singular Comedic Career

Last November, shortly after comedian and actor Robert Klein was confirmed as the recipient of 2024’s Bob Harrington Lifetime Achievement Bistro Award, producer Sherry Eaker and I attended a Saturday night comedy concert of his at the Argyle Theatre in Babylon, New York.

Klein was the whole show that night—aside from some assistance from Bob Stein, his musical director (and producer of some of his many HBO specials). There were no warm-up acts to pump up the audience for the main event. Klein seemed carefully attuned to his surroundings, his material was wide-ranging, and every ad lib had the potential to morph into a freewheeling, comic stream-of-consciousness.

Much of his set that night seemed tailor-made for Long Islanders of a certain age (and with a working knowledge of some common Yiddish expressions). At points he touched on politics, and though he seemed to artfully avoid anything too controversial, everyone got the point that he doesn’t suffer fools (or would-be autocrats) gladly. There were several utterances of his trademark “Oooh-OOOOOH-Oooh” cri de coeur: denoting a stumble into cosmic-level Crazy Town. He weighed in on contemporary nuisances—mocking the inane but persistent Jardiance jingle (“I have type-2 diabetes, but I handle it well…”). He also—with Stein at the piano—sang and played harmonica. His heartfelt hymn to colonoscopies was a crowd favorite. He ended the evening with his signature number: “I Can’t Stop My Leg.”

I thoroughly enjoyed the performance. But Sherry? During the show she laughed like I’ve never known her to laugh. She erupted into periodic giggle-fits on the train, all the way back to Manhattan.

Several weeks later, Klein and I chatted over the phone, in advance of the upcoming Bistro Awards gala at Gotham Comedy Club this April 1. We spoke about highlights from his 50-year-plus career, touching on his formative years in the Bronx in the 1950s (something he covers in detail in his very entertaining 2005 memoir, The Amorous Busboy of Decatur Avenue).

I mentioned that his Lifetime Achievement award is the first to be presented to a comedian instead of a musical performer. But I noted that it wasn’t quite that simple, because music has always been a key ingredient in his career. In fact, his first-ever public performance happened when he was still in high school: on Ted Mack‘s Original Amateur Hour, along with other members of his singing group, The Teen Tones. (View video here.) A couple of decades later, Klein would be nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical for 1979’s They’re Playing Our Song, starring opposite Lucie Arnaz. Still later, two songs he wrote for his HBO specials received Emmy nominations.

He told me that music was part and parcel of his Bronx childhood:

My mother took a few piano lessons as a child…. She couldn’t read music, but she could play anything you hummed, in the key of F with both hands. And I remember her talking with Marvin Hamlisch. I guess he came to my house. Maybe it was for my son’s bris—I don’t remember. But she was apologetic: “Oh, I can’t read music.” Marvin said, “Frieda, do you realize what you’re able to do?” And I guess she did. My father played a bad violin, and my sister and I sang around the piano…. My parents said I could carry a tune as an infant…. Later, on my own, I became a devotee of Johann Sebastian Bach and Handel and Mozart.

Laughter was also a valued commodity in the Klein household.

My father was extremely funny. He was a textile salesman—a college drop-out. He had been an excellent student at Stuyvesant High School and at City College, but he wanted to go into the business world, and he wound up in a schlocky job that he hated, with a 2% commission. But he was a wonderful clown and improviser. I guess he alternated between that and sadness, I suppose we’d call it “bipolar” today— nothing clinical. But he was very, very funny. So, comedy was a way of life in my house.

Young Robert was also exposed to professional comics during the family’s summer excursions to the Catskill mountains:

When my father had a good year, we were able to spend three weeks in a hotel in Woodbourne, and I saw a real, live comedian. Now, I loved comedians on television: Red Buttons, and Sid Caesar, of course was the king…. But here I saw live ones. And later on too, when I was a busboy and a lifeguard, I saw them come in. A comedian would come in in his Cadillac. And he worked 35 minutes, and the people would be just drained with laughter. And, for those 35 or 40 minutes, they forgot their troubles with their finances or their health or their children or their husbands or whatever. And I thought: That’s a wonderful way to make a living. You come in, you spread a little joy, you make money. You have a Cadillac.

Klein adds, though, that to consider embarking on a career as a comic would have been seen by family and neighbors as “absolutely Martian.”

He attended Alfred College in Allegany County, New York, with the intention of going on to medical school. But he wound up majoring in history and—more significantly—finding his passion while acting in college plays. Two of his professors, Duryea Smith and Ronald Brown, persuaded Klein’s father to allow Robert to pursue further dramatic training at Yale, though not without some resistance.

These two professors at Alfred University—Smith and Brown, with their tweeds and their pipes—they said: “Mr. Klein, he’s very talented, and we can get him into Yale.” At Amherst, Duryea Smith had been the roommate of the [future] dean of the Yale School of Drama. He’d only recommended two people in 30 years: a director and a light designer, and they both did well. So, I had no audition. And my father said, “Yale? To be an actor? Did Eddie Cantor go to Yale?”

Although his time in New Haven boosted his growth as an artist, he left the program after a year, deciding he was ready to pursue the rough-and-tumble business of show. At first, things seemed far from promising.

When I left Yale in the fall of ’63, I was 21. I was out of school for the first time in my life. No work. President Kennedy was assassinated…. It was awful, it was a terrible time. I had no connections. It was really desolate. And then Jimmy Burrows, who was my best friend at Yale and who would become the biggest television director in California, said, “I’m doing a revue on weekends. You get $35 and delicious German food at the Hofbrau Haus.” I had no tux. He lent me his. His father was Abe Burrows, the director and writer, and he was with William Morris for years. He had an agent come up to New Haven to see how his son was doing in that show. The agent, Bernie Sohn, took me aside and said, ‘You know, you’re terrific, and Second City is coming to town, and they need actors.” I auditioned with 15 or 20 other actors, including Fred Willard, whom I had never met. We did an improv together, and we got the job.

For Klein, the time with Second City (beginning in 1965) marked the official start of his career as an entertainer. He flourished in Chicago. In addition to Willard, he worked with comedian David Steinberg, who became both friend and competitor. Nonetheless, he was soon back in New York, cast in the ensemble of the Broadway musical The Apple Tree, directed by Mike Nichols.

Being in a Broadway musical was not enough for him, however. He moonlighted after the Apple Tree‘s evening shows, taking the mic at the Improvisation Club—better known simply as The Improv—on West 44th Street. Here he would learn the art and craft of stand-up comedy. He would also meet the man who would become his comedic mentor.

My “Yale Drama School for Comedy” was definitely Rodney Dangerfield. I met him at The Improv, and I didn’t know who he was. He was certainly not a superstar then. I think he had done one Merv Griffin at that time. He had reinvented himself from “Jack Roy.” And I was with him practically every day for 10 years. I followed him around and saw how it’s done. He also was a rarity [then] in that he wrote his own material—and brilliantly. So, I did too. I don’t know, I just picked up the performance techniques, the construction of a joke.

With help from Dangerfield, Klein landed a manager, Jack Rollins, who famously partnered with Charles Joffe in talent management and, later, in film production.

I kept on telling these agents at William Morris, “Hey, come on, you gotta see me. I’m doing stand-up.” “Oh, we’ll come, we’ll come, we’ll come….” They didn’t come. And Rodney said, “Fuck William Morris. You need a manager. Jack Rollins. He’s the best in the business: Woody Allen, Joan Rivers, Nichols and May, blah, blah, blah. I’m gonna tell Jack about you.”

So, he convinces Rollins and Joffe to come to see me at the Improv…. But the night before, I’m driving on Seventh Avenue with Rodney, which was taking your life in your hands. He double-parks his Chevy convertible in front of the Stage Delicatessen. Or was it the Carnegie? I think by that time it probably was the Carnegie. Jack is at a table just like [in] Woody’s film Broadway Danny Rose: the delicatessen scene. (Jack was in that scene actually.) And Rodney says, “Jack, this is the guy I was telling you about.” And I’m so embarrassed, interrupting his pastrami sandwich. And [Rollins] looks up. He says, “A good face for motion pictures.” Anyway, then the big night comes, and Rollins is late as usual. He was kind of casual about that. When they found out Rollins was coming, the entire William Morris contingent came down, including a vice president, Lee Stevens. And the Merv Griffin producers, Bob Murphy and all of them, came down. And Lee Stevens is looking at his watch, you know: “I gotta get the last train back to Great Neck.”…. Jack finally arrived. I killed ’em. And he said, “Lad, we’d like to work with you.” And that really set me going on a wonderful career.

Things picked up relatively quickly, in fact. In 1968, Klein appeared for the first time with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. He quickly became one of Carson’s favorite guests:

When I did Jimmy Fallon a couple of years ago, they gave me a plaque with the date of every one of my Tonight Shows with Carson and with Jay Leno. Ninety-three of them, I think—including about 10 or 15 as guest host. I also did an awful lot of shows with Dick Cavett and guest-hosted for him. And I made frequent appearances on David Letterman’s show.

The Klein brand of comedy—cerebral on the one hand and physical and zany on the other, with a notable scarcity of “blue” humor—would make him a natural for comedy concerts on college campuses, something that became a core element of his career for many years.

But he also had an early engagement at a Las Vegas hotel that opened his eyes to the harsher side of the business.

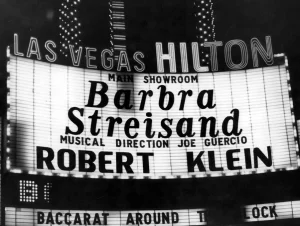

Nightclubs—casinos, certainly—seemed kind of tawdry. I did work early in my career opening for Barbra Streisand at the Hilton. And I was there a little prematurely. I was used to Greenwich Village and The Improv and a hip audience of semi-show-business types or—in the Village—beatniks or whatever. And here I am with drunken people on New Year’s Eve in Vegas. I had hit-and-miss shows. I remember Rodney brought Jack Benny to see me on one of those off nights. I mean, I was never booed off the stage or anything, but it was very iffy. And I used the word “shit” or something, and Benny turned to Rodney and said, “The kid works dirty.” I know he saw me subsequent to that many times on The Tonight Show, and I’m sure he had…a better opinion of me. Anyway, Streisand was fantastic. You know, a lot of people had trouble with her. I also did The Owl and the Pussycat with her, one of her first movies.

Incidentally, although he is widely known as someone who does not “work dirty,” Klein points out that he does, in fact, employ profanity onstage—though sparingly. He uses it “as an adult would.” He sees himself as akin to a serious author, rendering human speech without self-censorship, but not reveling in smut for smut’s sake.

The 1970s began for Klein with a job hosting a CBS summer-replacement for Glen Campbell’s program. Called Comedy Tonight, it teamed him with Madeline Kahn and Peter Boyle, both of whom he loved.

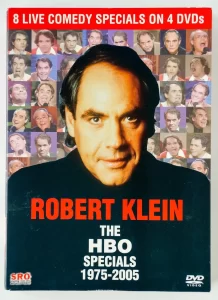

A bit later, he would make a series of highly popular comedy recordings, starting with A Child of the 50’s in 1973. These earned him two Grammy nominations. 1975 was an especially, big year. Klein hosted the fifth-ever episode of Saturday Night Live (appearing in the soon-to-be beloved “Cheeseburger. Cheeseburger” sketch) and also taped the first of nine comedy specials for Home Box Office. He was the first comedian to do such a special. (I was surprised when reminded that HBO was even around that far back!)

A guy named Harlan Kleiman called my managers and said he’d like to have me do a “live” taped—concert. But a whole hour, never mind the six-and-a-half minutes of The Tonight Show or anything like that. And that was revolutionary. They sent an art director to look at various places where I was booked—colleges. What would be a good-looking auditorium? They loved the busts of the old geezers at Haverford College in Pennsylvania. And Bryn Mawr and Haverford were presenting Robert Klein in a concert, and they decided to film there…. At that time, HBO had about 100,000 subscribers. Many people didn’t see the first two or three shows.

Klein married opera singer Brenda Boozer in 1973, and they became parents of a son, Alexander (“Allie”). The marriage to Boozer ended in 1989. About a year ago, Klein became the grandfather of a girl-child named Iris, whom he finds purely delightful.

In the later decades of his career Klein has appeared regularly in films, including Primary Colors (again for Mike Nichols), Two Weeks Notice, and How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days. Though he has guest-starred in TV series over the years—including in the recent reboot of Will & Grace, as the father of Grace Adler (Debra Messing), taking over the role from his friend, the late Alan Arkin—he was not a fan of sitcoms, and he tended to avoid both watching them and headlining in them. He continued his theatrical career also. Among his later New York stage credits is Wendy Wassertstein’s The Sisters Rosensweig (again with Madeline Kahn), both Off Broadway and on (1992-93). That performance earned him Obie and Outer Critics Circle awards for Best Actor.

He has always striven to be more than just a comedian, a determination he found admirable in several of his comic forebears and peers.

A comedian should be a one-man show. Lenny Bruce was a one-man show…. At the end, when he was sick and addicted and just relating his court cases—that’s not it. I’m talking about when he did voices and parodies. And Jonathan Winters was like that too….

Richard Pryor and George Carlin made funny faces, they made funny gestures, they patrolled the stage. They were wonderful entertainers as well as comedians. Their early stuff, before they became, you know, more profane, was just as funny. I mean, the Hippy Dippy Weatherman of George Carlin…or Pryor, whom I befriended at the Improv. He was collegiate. He used to wear these sweaters and go on Merv Griffin…. Pryor also disappeared for a year and a half… He wasn’t really political, but in ’68 there were riots and assassinations, and he came back more authentic. I once asked him, “What college did you go to?” And he laughed for five minutes. He was brought up in a brothel, you know.

Now semi-retired, Klein enjoys a relatively quiet life in Briarcliff Manor in Westchester County. He works out regularly with a trainer and continues his longtime interest in history.

I’m reading a lot of World War II and World War I. I go back to the good old days! I can’t read the paper. It’s too depressing. I’m reading a book about hunting the Jews in Poland. And I just finished one about a guy who joined the underground. Now I’m reading Toni Morrison. I’ve never read more in my life. And I love it. On my iPad.

(Moments later, he concedes that he, in fact, reads the New York Times—also on his iPad.)

Though he is happy to be recognized and remembered by fans, he’s especially proud of the long list of successful comedians who have been influenced by him and his comic approach. The roster includes Jerry Seinfeld, Jay Leno, Jon Stewart, Bill Maher, the late Richard Lewis, and many more.

At the supermarket or in town here, in Briarcliff, I’m no big deal. Everyone knows me. They might say, “Ah, I saw you in a movie…” But people made a fuss over me when I was at the Spamalot [revival] opening. So, I’m reminded that people were listening. Or they’ll take out a line from a Tonight Show I did in 1984 that I may never have done again….

The public may not know me as much, but the business—my own colleagues—they participated in that documentary about me [Marshall Fine’s Robert Klein Still Can’t Stop His Leg, 2016]. And also, for my 80th birthday, a number of them participated in a video.

To think that all these people—very big, big stars—were largely influenced by me? It’s a great source of satisfaction.

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.