Cabaret Setlist: “Let’s Not Talk About Love” – Music and Lyrics by Cole Porter

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Article #24 in this ongoing series.

In 23 installments of Cabaret Setlist, how have we not yet looked at a song by Cole Porter? One of musical theatre’s most respected composer-lyricist hyphenates—along with Irving Berlin, Stephen Sondheim, and Jerry Herman—Porter was exceedingly prolific. A 1983 collection, The Complete Lyrics of Cole Porter (edited by Robert Kimball), brims with some 800 entries, a good number of which can be found on dog-eared pages of the American Songbook: “Let’s Do It, Let’s Fall in Love,” “Night and Day,” “Begin the Beguine,” “Don’t Fence Me In.” There are also, of course, a slew of familiar numbers from the Indiana-born composer’s big Broadway scores (Anything Goes; Kiss Me, Kate; Can-Can).

On the other hand, there are plenty of songs in the Porter catalog that singers in 2023 would have no use for.

Take, for instance, Porter’s rah-rah college efforts from his earliest days as a tunesmith, while a student at Yale. Or songs that are apparent rough drafts of eventual favorites. (Both “The Sponge” and “The Scampi,” for instance, seem to be precursors to “The Tale of the Oyster”—a Porter cabaret favorite.)

There are lyrics that haven’t aged well for reasons having to do with political sensitivity. Case in point: Mississippi Belle’s “Hip, Hip, Hooray for Andy Jackson,” which sang the praises of “Old Hick’ry, the people’s friend.” (No mention of the Trail of Tears.)

Still, there are plenty of Porter songs that are lesser known but could still work successfully in 2023 cabaret acts. Today’s selection may be one of them.

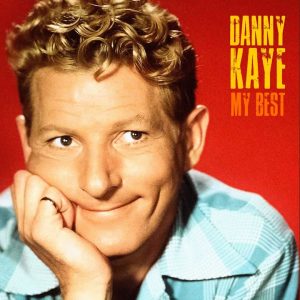

Oh, Kaye!

The musical comedy Let’s Face It!—about a trio of bored, wise-cracking women who hire soldiers as companions—opened on Broadway in late October of 1941, just a little more than a month before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The show received reviews that may have surprised Porter and librettists Herbert and Dorothy Fields with the generosity of their praise.

The musical comedy Let’s Face It!—about a trio of bored, wise-cracking women who hire soldiers as companions—opened on Broadway in late October of 1941, just a little more than a month before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The show received reviews that may have surprised Porter and librettists Herbert and Dorothy Fields with the generosity of their praise.

The show’s cast included several young performers who would go on to have stellar careers: Danny Kaye, Eve Arden, Vivian Vance, and Nanette Fabray.

But—no big surprise—mostly Danny Kaye. He was never one to stand in the back.

But—no big surprise—mostly Danny Kaye. He was never one to stand in the back.

It was Kaye who introduced “Let’s Not Talk About Love” to the world. The song was a natural follow-up to the actor’s big song in 1940’s Lady in the Dark: “Tchaikovsky (and Other Russians).” Both songs contained challenging clumps of verbiage for Kaye to chew and expel.

Porter had actually written a verse for Arden called “Let’s Talk About Love.” But, according to Robert Kimball, there remains confusion about whether or not her opening salvo was ever performed. Only the Kaye retort, Kimball notes, appears in the Let’s Face It! script.

Here is a Kaye studio version of the song: Listen.

I’ve Got a Little List

“Let’s Not Talk About Love” is a list song, in the spirit of more-famous Porter titles like “Let’s Do It” and “You’re the Top.” In this case, the list consists of topics deemed by the song’s protagonist to be better fodder for conversation than anything having to do with the dreaded “L” word. Brooks Atkinson, in his New York Times review of Let’s Face It!, singled out this composition, noting that it “restores the patter song to its ancient eminence as a test of memory and wind.”

“Let’s Not Talk About Love” is a list song, in the spirit of more-famous Porter titles like “Let’s Do It” and “You’re the Top.” In this case, the list consists of topics deemed by the song’s protagonist to be better fodder for conversation than anything having to do with the dreaded “L” word. Brooks Atkinson, in his New York Times review of Let’s Face It!, singled out this composition, noting that it “restores the patter song to its ancient eminence as a test of memory and wind.”

William McBrien, in his 1998 Porter biography, writes of Porter’s long-held appreciation of the operettas of W.S. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan. At the time of his final major theatrical endeavor, Silk Stockings (1955), Porter, in an interview for the New York Herald Tribune, made the following remarks about what had seemed a preoccupation of sorts:

“I’m becoming less and less interested in tricky rhymes. I think I used to go overboard on them. In Yale, I was rhyme crazy. That was due to the fact that I was Gilbert and Sullivan crazy. They had a big influence on my life.”

Certainly, there are strong echoes in “Let’s Not Talk About Love” of G&S’s humorously self-conscious quests to pile on the rhymes while galloping through multiple measures of “patter.” The Pirates of Penzance’s “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major General” comes quickly to mind, with its jokily mock-desperate rhyming of “strategy” with the nonsensical expression “sat a G.” In “Let’s Not Talk…” Porter arguably out-Gilberts Gilbert by creating rhymes that cleverly incorporate a Boston accent:

Let’s check on the veracity of Barrymore’s bibacity

And why his drink capacity should get so much publacity,

Let’s even have a huddle over Ha’vard Univasity,

But let’s not talk about love.

At the end of the song, the ever-hammy Kaye would certainly have enjoyed riding this avalanche of rhyme:

And so, instead of gushin’ on,

Let’s have a big discussion on

Timidity, stupidity, solidity, frigidity,

Avidity, turbidity, Manhattan, and viscidity,

Fatality, morality, legality, finality,

Neutrality, reality or Southern hospitality

Pomposity, verbosity,

You’re losing your velocity,

But let’s not talk about love.

Note that while there does exist an English word “viscidity” (meaning stickiness), in this lyric, Porter uses the term for the word “vicinity,” apparently as spoken by someone with a bad head cold.

As for the melody in the section of the song quoted just above…does it sound at all familiar? I notice a similarity to certain measures in a Stephen Sondheim list song: Company‘s “The Little Things You Do Together” (“It’s things like using force together, / Shouting till you’re hoarse together…” etc.). I’d like to think that Sondheim had a tiny but sly Cole Porter ear worm by his side while working on “The Little Things….” (In an essay in his book Finishing the Hat, Sondheim did count “Let’s Not Talk About Love” among Porter’s “memorably melodic” list songs. So maybe I’m not entirely crazy.)

Check Expiration Date

When you listen to the words in the Danny Kaye clip above, you’ll notice that they’re considerably different from the ones printed in Robert Kimball’s book of Porter lyrics.

When you listen to the words in the Danny Kaye clip above, you’ll notice that they’re considerably different from the ones printed in Robert Kimball’s book of Porter lyrics.

Porter’s original Broadway lyric, for instance, includes several references to political figures—people you’ve likely never heard of. How well-remembered, for instance, is “Senator Glass” (i.e., Carter Glass of Virginia) or “Ickes” (i.e., Harold L. Ickes—pronounced “ICK-eez”—a one-time U.S. Secretary of the Interior)?

You possibly don’t know about “Hamilton Fish,” either, unless you’ve listened to Rachel Maddow’s recent podcast, Ultra. (Which I recommend you do!)

With all of these quick-to-turn arcane allusions, how long a shelf life could a song like this one have?

Fortunately, “Let’s Not Talk About Love” also contains many references to movies and movie people. From the mid-1930s, Porter had been a strong presence in Hollywood as well as on Broadway. And he clearly liked to dish about film stars. Savvy cabaret audiences today will likely identify most of the Tinseltown celebrities mentioned in the song (Betty Grable, Hedy Lamarr, Bob Hope, “Sammy” Goldwyn), more quickly than they will the referenced political figures.

And yet, these days, when some young adults are unsure about who someone like Judy Garland or even Marilyn Monroe was, don’t the names that figure in “Let’s Not Talk About Love” present an increasingly hopeless puzzle?

As singer Amber Petty told me: “’Wallace Beery’ isn’t a name trending on Tik-Tok.”

Clearly, this song was not one designed for posterity. It was built to be topical. And that presents a certain problem for singers who want to resurrect it. Unsurprisingly, there have been very few resuscitations of this song since 1941.

Art or Artifact?

To start with, Let’s Face It! has not been a much-revived musical, although there have been a couple of concert versions of it (in San Francisco and New York City) within the last quarter century.

A 1943 film version of the musical discarded some Porter songs (along with the exclamation point in the show’s title) but did retain “Let’s Not Talk About Love.” In the movie it was sung by an agitated, rambunctious Betty Hutton. (Was there truly any other kind?) Get a load of Hutton here.

A 1943 film version of the musical discarded some Porter songs (along with the exclamation point in the show’s title) but did retain “Let’s Not Talk About Love.” In the movie it was sung by an agitated, rambunctious Betty Hutton. (Was there truly any other kind?) Get a load of Hutton here.

While Eve Arden reprised her role in the movie version, Bob Hope replaced Kaye. Note, also, that the Broadway lyric “Try to picture Paramount minus Bob Hope” has been retained. That’s just the sort of cheeky, self-referential “in” joke that Hope and Bing Crosby reveled in in their “Road to…” movies. (For the record, Let’s Face It was, indeed, a Paramount release.)

There are some updated lyrics in the Hutton version that mark the difference between 1941 and 1943, notably an allusion to the wartime ban on sliced bread. Glass, Ickes, and Fish, meanwhile, are nowhere to be found.

Studio censors, too, apparently took action that changed the lyrical content. Note that instead of asking listeners to “get in the altogether and enjoy a short swim,” Hutton prompts them to don a bathing suit for more-modest aquatic play.

In 1999, when singer Hubbell Pierce and pianist William Roy recorded a likable but relatively subdued version of the song for a Porter collection, they included some of the more obscure political lyrics. Notice that, unlike Kaye, Pierce doesn’t increase the song’s speed in the final measures. This seems to be in keeping with Pierce’s generally unexcited, ennui-riddled approach to Porter. I find Pierce’s rendition pleasingly Cowardy in its world-weariness. (Get blasé with Hubbell Pierce here.)

In the 21st century, most revivals of the songs have presented it as a historical artifact. In 2017, NYC’s Encores! series interpolated it into a new iteration of a different Porter score, that of The New Yorkers (1930). In that production, it was sung robustly by Arnie Burton. (Enjoy the Burton clip.)

A decade earlier, actor Brian Childers had included “Let’s Not Talk…” in his Danny Kaye bio-show, The Kid from Brooklyn. It also appeared in Childers’s one-man version: An Evening with Danny Kaye. He has since sung the number in other contexts, including this 2019 version (performed at Don’t Tell Mama). (Listen to the Brian Childers rendition.)

When planning the Kaye bio show, Childers pored over the star’s repertoire and discovered this song. He liked it immediately, though he knew that it would present challenges with its rapid-fire bouts of tongue (and synapse) torture.

“To learn it, I used every trick in my bag…” Childers says now. “I’m an incredibly visual learner. I love to write the words out so I can see them.” He also employs an “alphabet trick” by which he memorizes items in lists, using starting letters that spell out “a silly acronym.”

The inclusion of the song in The Kid from Brooklyn helped Childers make points about the Kaye psyche: “We used it to show Danny’s quirkiness and [avoidance of talk] about anything close to love or affection.”

Childers was very aware of the dated allusions. In the version presented above, he (like Kaye in the studio recording) retains the short introductory verse and avoids using some of the more mystifying lyrics. (Fiorello La Guardia and Eleanor Roosevelt make the cut, but not Glass, Ickes or, Fish.) The singer finds enough relevance in the song to keep performing it:

“While outdated, it still can be pretty fun to sing, and…the patter at the end is still a showstopper, so I think it shouldn’t be thrown out just yet.”

The Farr Side

With her 2014 Bistro Award–honored cabaret show In the Still of the Night (performed at the Laurie Beechman Theatre), Shana Farr used songs and other written works by Coward and Porter to spin her own personal narrative—about a woman who finds unsatisfactory experiences with romance before giving up on things of the heart and then, ironically and unexpectedly, finding true love at last. She adopted a persona for the show that, she says, was not exactly herself, but a decidedly close approximation.

Farr scoured Kimball’s lyric collection, as well as a similar book, Barry Day’s Noël Coward: The Complete Lyrics, looking for words that would help her tell her story. “Let’s Not Talk About Love” immediately captured her attention. “I didn’t know all the political names and situations that Cole had written [about],” she told me in a recent phone interview. “I did look all of that up.” (Among other things, she added the word jerboam—i.e., an oversized wine bottle—to her vocabulary.)

What she liked in the song was its attitude of exasperation. “It just stuck out to me as the right song for that three-quarters-of-the-way-through-it moment in the show where I was ready to chuck it all in and give up [on love].” (Hear Shana Farr’s version here.)

She explains that, at the beginning of the song, the lyrics are presented with an air of nonchalance: “Let’s talk about frogs, let’s talk about toads. I don’t care what we talk about! But then…with all of those words—‘timidity, stupidity, frigidity, rigidity’—it was like a train running top-speed to a…wreck.”

Farr says that she would not have presumed to update any of the Porter lyrics, but she did shift some of them around for dramaturgical reasons. She wanted to ensure that all the “in-your-face, heightened, rude” references (to, for instance, the use of “dope” and the “inhumanities” of Adolf Hitler) came nearer the big finish.

Her rendition is mostly “spoke-sung”—perhaps not surprisingly, as she’d taken a shine to the song before even hearing its melody. One misses the lilt of Farr’s clarion soprano singing voice on the number, but she was probably right to put the lyrical content above melodic considerations:

“When it comes to patter songs, in my opinion, the music is there to use for specific moments and points you want to make, but…once you make [the songs] your own, you kind of bring your own rhythm and emotion to it.” (Farr even jokingly suggests that “Let’s Not Talk…” might successfully take on a hip-hop vibe by placing a beatbox rhythm beneath the melody and then rapping the lyrics.)

In rehearsals, she and her music director, Jon Weber, experimented to find the right pace for the song, especially in the breakneck-speed conclusion. At one point, Farr had reached her limit regarding acceleration. “We have to start this a little slower,” she told Weber, “so that we can then speed up for the very end.”

Like Childers, Farr developed her own exercises to memorize Porter’s lyrics. She would actually envision the words as printed on the page, along with other visual cues she’d stored in her mind. At a certain point, it became a simple case of relying on muscle memory. She told me that she could probably relearn the song in a matter of hours just by reinforcing the muscle memory in her lips.

Petty Grievances

Creating updated lyrics for Cole Porter songs is nothing new. Biographer McBrien writes that in the winter of 1934-35, the “game around town” was writing parodies of “You’re the Top”—often ones with risqué lyrics. McBrien tells that one of these naughty versions was actually written by Porter pal Irving Berlin:

You’re the burning heat of a bridal suite in use,

You’re the breasts of Venus,

You’re King Kong’s penis,

You’re self-abuse.

At the time, according to McBrien, the music publisher (Harms) tried to stop or at least slow instances of copyright infringement on “You’re the Top,” but McBrien also notes that Porter simultaneously encouraged emulation by prompting his second cousin, Ted Fetter, to write parodies of “You’re the Top” and other of his hits.

The protected status of parodies, by the way, was fortified in a 1988 Supreme Court decision (involving Larry Flynt of Hustler magazine).

Some of this may have been in Amber Petty’s mind when she decided to try her hand at creating new, updated lyrics for her rendition of “Let’s Not Talk About Love,” for a 2015 cabaret show, We Don’t Need Another Hero, performed at the Duplex. (Hear Amber Petty and her updated lyrics in this clip.)

“At the time I was in a parody musical called 50 Shades! The Musical. It was a parody of Fifty Shades of Grey that used practically the whole title—and character names. Though we were nearly sued when we performed in Scotland, the creators consulted lawyers, and our show was in the clear under ‘fair use.’ Now, did I ask a lawyer before doing my cabaret show? No. But after my experience in 50 Shades, I believed my version could be considered parody. And I thought somebody would have to be real desperate to sue a one-off cabaret show for an old Cole Porter song.”

According to Michael Kerker of ASCAP, Petty is correct about this. “Using the ‘new’ lyrics in a cabaret setting is not really a problem,” he wrote to bistroawards.com. However, musicians making a commercial recording should consult with the copyright holder for permission to insert new material.

Petty had come to know the song on what she calls “one of my ‘let’s find musical bootlegs or weird movie numbers’ YouTube crawls.” She’d unearthed the Betty Hutton version.

“Betty Hutton’s delivery is so fun and wild, the song’s cheeky and fun, and it gave me a reason to Google old references. Fun! I wish I were as good as Betty Hutton, but her funny, just-at-the-edge-of-over-the-top performance is exactly what I love to do. So, I thought I’d give it a try.”

The decision resulted in a mammoth challenge. “It’s not just the tongue-twisting nature of the diction,” Petty says, “but you also have to be in each comedic beat. I felt like I was always a touch behind.”

As for the new lyrics, her experience turned out to be a mixed bag. She is proud of these lines:

Let’s talk about food,

Let’s have a nice snack

Let’s cry a single tear that ’90s clothing is back.

But, she says, other of her new references “were a little too timely, so, seven years after my show, some of my lyrics are dated!”

For starters, there was her wisecrack about a Hollywood casting choice.

“At the time I was very annoyed that Cameron Diaz played Miss Hannigan in the new (at the time) Annie film and that she was being lauded as a comedian. But no one remembers that movie now, and it seems like I’m making fun of her for no reason. So, those lyrics would be the first to go.”

Final Tips

If you decide to throw caution to the wind and take a spin with your own interpretation of “Let’s Not Talk About Love,” Farr and Petty have some final words of advice.

“Enunciate—and don’t go too fast,” reiterates Farr.

Petty (who told me I can let singers know that they are free to use any of her lyrics) seems to be in agreement: “Add extra time for rehearsal and start slow…really get your words down, and speed it up until you get the manic ending of your dreams!”

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.