Cabaret Setlist: “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries” – Music by Ray Henderson, Lyrics by Lew Brown

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Article #23 in this ongoing series.

When times get tough, people look for escape routes, right?

Think of those 1930s Warner Bros. movies with their intrepid gold diggers and elaborate Busby Berkeley production numbers. Those films have long been cited as vehicles that helped people forget their troubles and get happy: moments of silly fun in the shadow of the Great Depression.

And that sort of thing happens in our own twisty times. It’s not easy to steer clear of numbness and/or despair right now, what with the stubborn menace called COVID, a war in Ukraine, shocking inflation, culture-changing decisions from the Supreme Court, and a political divide that makes the Grand Canyon look like some minor gully.

But we can play pickleball and Wordle. We can celebrate another shark week.

Songs, too, can aid and abet escapist tendencies. Pop music now, though, is so splintered into genres and sub-genres that it’s hard to assess the kind of role it plays in salvaging our mental equilibriums during crisis times. There’s certainly some dippy, bubble-gummy pop music out there for us to latch onto (often with “oh-oh-ohs” and “ooh-ooh-oohs” in lieu of actual lyrics), but there’s also a measure of gravitas. A recent visit of members of the South Korean pop group BTS to the Biden White House may have seemed trivial: a stunt, a 1930s-like dip into feel-good-ism. But members of that boy band had actually gone to Washington on a serious political mission: eradication of anti-Asian sentiment.

Maybe the equation has never been a simple one. In today’s Cabaret Setlist, we’ll take a look at a classic pop song from the Great Depression: “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries.” While I’ve been aware of this song most of my life, I’ve tended to dismiss it as a sappy ditty with the most hackneyed and naive of messages. I never paid much attention to it, really.

But I heard it recently when Carole J. Bufford sang it (beautifully) in her Judy Garland 100th birthday show at Birdland. That performance opened my eyes. Maybe the only thing naïve about the song was my understanding of it.

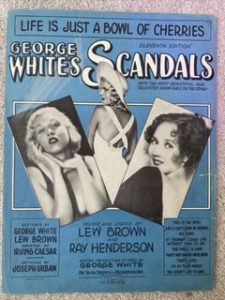

The Book(ing) of Merman

“Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries” was introduced to the world on Broadway, in George White’s Scandals of 1931, where it was sung by young Ethel Merman. Here’s a later, studio version of the number from E.M., which gives you a sense of the whole piece, including the song’s short verse (“People are queer…” etc.). Billy May created this arrangement. Hear Merman here.

“Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries” was introduced to the world on Broadway, in George White’s Scandals of 1931, where it was sung by young Ethel Merman. Here’s a later, studio version of the number from E.M., which gives you a sense of the whole piece, including the song’s short verse (“People are queer…” etc.). Billy May created this arrangement. Hear Merman here.

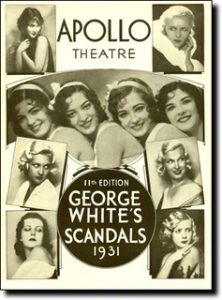

The Scandals shows appeared on Broadway from 1919 to 1939. Producer George White had been responsible for assembling the songwriting team of Buddy Da Sylva, Lew Brown, and Ray Henderson in 1924. Da Sylva and Brown were mostly lyricists, with Henderson the composer, but there was overlap in lyrical and musical contribution among the writers, varying from song to song.

The three men were seasoned tune-scribes when White hired them to provide a score for the Scandals series of revues.

According to Philip Furia in his book Poets of Tin Pan Alley, De Sylva had had success writing lyrics for “ten-cent-philosophy” songs—pop numbers that took an upbeat, platitude-filled look at bad situations. Both “Look for the Silver Lining” (with Jerome Kern) and “April Showers” (with Louis Silvers) advised patience during tough times: hang on long enough and the weather will improve, your spirits will pick up.

Brown’s early output included WWI-related songs with composer Albert von Tilzer. He began working with Henderson in 1922.

Apart from his work with the team of three, Henderson had a major success with “Bye Bye Blackbird” (lyric by Mort Dixon).

Together, the three collaborators wrote a number of evergreen titles for early editions of the Scandals, including “Birth of the Blues” and “Lucky Day.” But, by 1931, Da Sylva had broken from the team, leaving Brown and Henderson to work as a duo. Unfortunately, their songs for the 1931 Scandals seemed to have been sub-par. As Bob Thomas explains in his Merman biography, I Got Rhythm, White brought the fresh young star in to help salvage the show, and she insisted that new songs be written  expressly for her. That’s some clout for a performer who’d had only one previous Broadway credit. But what a credit it was—the 1930 Gershwin show Girl Crazy, in which the Merm had unleashed “I Got Rhythm” onto the planet! In any event, “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries” was custom-made for Merman, who sang it early in the show’s first act. It definitely made its mark.

expressly for her. That’s some clout for a performer who’d had only one previous Broadway credit. But what a credit it was—the 1930 Gershwin show Girl Crazy, in which the Merm had unleashed “I Got Rhythm” onto the planet! In any event, “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries” was custom-made for Merman, who sang it early in the show’s first act. It definitely made its mark.

“Merman took no part in the [Scandals] sketches or in anything other than Merman,” musical theatre historian Ethan Mordden writes in Sing for Your Supper, his book about Broadway musicals in the 1930s. Mordden notes that, in this show, Merman just planted her feet onstage and put over her musical numbers.

One of her co-stars in the show was Rudy Vallée. He would sing on one of several versions of “Cherries” recorded on the heels of its Broadway debut; listen here.

One of her co-stars in the show was Rudy Vallée. He would sing on one of several versions of “Cherries” recorded on the heels of its Broadway debut; listen here.

Existential Matters

Henderson’s melody for “Cherries” is charming and easygoing. with a nice lilt. You can imagine a soft-shoe dance break midway through the number. To my ear, the melody unwittingly echoes that of Cole Porter’s “Take Me Back to Manhattan” from 1930’s The New Yorkers. The perky quality of the tune may add to its reputation as an everything-is-peachy-keen sort of number.

Maybe my misunderstanding of the song can be attributed to a single word in the lyric—“just.” I’d always assumed that the title could be paraphrased as “Life is just as swell as a bowl of cherries.” But now I’ve come to believe that that it’s meant as a synonym for only. In other words, “Life is no more significant than a bowl of cherries—and we’d best get used to that.”

“Cherries” raises some elemental questions—the kind you might not expect in a daffy Broadway revue devised largely to showcase fetching showgirls. “Why are we here? Where are we going?” Brown asks in the song’s short verse. He sees life as “too mysterious”—something too big to be fully understood by feeble human brains.

The song certainly does not espouse an “it’s all good” view of the world. Not for a second. Instead, Brown suggests in the refrain that while prosperity may (or may not) be just around the corner, death certainly is. “You can’t take your dough when you go, go, go,” he writes. The lyric goes on to observe that “the strongest oak must fall.” Even ancient forests have an expiration date!

There’s also what could be interpreted as an anti-capitalist sentiment in Brown’s skepticism about private property ownership:

The sweet things in life to you were just loaned,

So how can you lose what you’ve never owned?

Fortunately for Brown (and Merman), nobody who turned up later on the House Un-American Activities Committee seems to have gone bonkers over this lyric.

In the Pits?

While researching the song, I found online a word histories article devoted to the lineage of the phrase “Life is a bowl of cherries.” This article’s unnamed author finds the earliest printed instance of the expression in an article in a New Jersey newspaper in 1928—about the life of manicurists on ocean liners!

This author also quotes what a critic of Vallée’s performance of the song had to say in 1931:

“The words go on philosophically about laughing and being gay with these cherries of life. That’s alright, Rudy, as long as the cherries are sweet, but what about it when you reach way down in the bag and draw out a bitter sour one. What then?”

But here’s a different angle. Later in this word histories article, the author notes that, in the 1920s, “bowl of cherries” had apparently been a “Broadway phrase” synonymous with “hot air” or “empty talk.” If you take that connotation into consideration, Brown’s title lyric is outright cynical.

The song is short and sweet, even when the verse is included. A second refrain can be heard in the Rudy Vallée recording presented above. It contains the following cryptic lines, which Vallée prefaces by saying he’ll perform while impersonating performer Willie Howard. (Willie, along with his brother Eugene, had appeared alongside Vallée and Merman in the 1931 Scandals):

At eight each morning I have got a date

To take my plunge ’round the Empire State.

You’ll admit it’s not the berries

In a building that’s so tall.

These lyrics remain a mystery to me. I wondered at one point whether they referred to suicidal “plunges” from skyscrapers in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash. But, if so, why plunge ’round and not plunge from?

Here’s, perhaps, a clue: Sources reveal that the 1931 Scandals included a Broadway salute to the Empire State Building, which had been opened months before the show’s debut. The now-inscrutable lyric sung by Vallée may have been an allusion to that long-forgotten theatrical sequence.

As time passed, “Life is just a bowl of cherries” came to be used almost exclusively in an ironic way—in disparagement of the very rose-colored-glasses worldview it seemed on the surface to espouse. The phrase appeared quite regularly in pop culture, as late as 1978, when American humorist Erma Bombeck borrowed it for the title of one of her books: If Life Is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I Doing in the Pits?

Cherry Pickings

The song “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries” has not been front of mind for many people in recent decades, but it has been performed and recorded by pop and jazz singers with some regularity since Merman first “put it over.”

Young Jaye P. Morgan charted with the song in 1950. The number helped launch her career.

Judy Garland took some spins with it—here’s a video of a performance from her 1963-64 TV variety show. It’s one of those Garland numbers that crescendo from nursery rhyme simplicity into a voraciously happy, show-stopping cyclone in a matter of a couple minutes. The interpolated “wiggle your ears” lyric at song’s end can be endearing or irritating, depending on your mood. This augmentation sounds a lot like what arranger Roger Edens would do when souping up other Garland tunes, most notably “San Francisco.” Notice that instead of singing “You work, you save, you worry so…” Garland sings “You work, you slave, you worry so….” Was she thinking of her MGM days? Watch here.

In the early 1960s, the song had something of a resurgence. Paul Anka, Debbie Reynolds, and Maurice Chevalier were among those who took it on. One of the more unexpected renditions was recorded by the Platters in 1960. (Listen here.) This track never, however, attained the iconic status earned by that group’s retooling of the 1934 Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach classic “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”: a major ballad of teenage angst in 1958.

In the early 1960s, the song had something of a resurgence. Paul Anka, Debbie Reynolds, and Maurice Chevalier were among those who took it on. One of the more unexpected renditions was recorded by the Platters in 1960. (Listen here.) This track never, however, attained the iconic status earned by that group’s retooling of the 1934 Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach classic “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”: a major ballad of teenage angst in 1958.

A lush ballad rendition was recorded by Doris Day in 1967 but was not released until the mid-1990s. One would expect an optimistic, lilting version from Day. But she makes the slow and thoughtful approach work nicely. I find the instrumentation in the verse especially warm and tender; hear it for yourself.

Carmen McRae recorded a jazz-tinged version of “Cherries” in 1965, brimming with va-voom (along with an embellished melody line). It’s worth a listen—a good reminder of what a singular talent McRae was—here.

Carmen McRae recorded a jazz-tinged version of “Cherries” in 1965, brimming with va-voom (along with an embellished melody line). It’s worth a listen—a good reminder of what a singular talent McRae was—here.

“Cherries” returned to Broadway after more than a half century when it was used as the opening number of the Bob Fosse book musical Big Deal (1986). There the song was performed by Valarie Pettiford, who would repeat her performance in the 1998 Broadway revue Fosse. Pettiford would go on to receive a Bistro Award in 2007 and even opened the awards show with “Cherries.” Here she is performing “Cherries” on the Fosse cast album.

“The Air Around a Clear Statement”

It seems certain that “Cherries” is not going away anytime soon. In fact, it’s the (pre-encore) closer for Elena Bennett and Fred Barton’s charming show Swing Out Under the Moon (next performance September 20 at Pangea), in which Bennett sings it robustly.

Also, Klea Blackhurst will no doubt keep on singing it.

Throughout her career, Bistro recipient Blackhurst has been closely associated with the legacy of Ethel Merman. “Cherries” was a key number in Everything the Traffic Will Allow, Blackhurst’s 2001 Merman tribute show (and subsequent live recording). She has performed this program many times over the last two decades.

“It’s the one everybody books,” she tells me with mock perplexity. “I keep saying, ‘I have other shows, you know.’ They don’t care.”

One of the things Blackhurst set out to do with her show was include at least one number from each of Merman’s major endeavors in musical theatre: thirteen original Broadway musicals, along with a 1966 reprise of Annie Get Your Gun and a stint as the last Dolly Levi in the original Broadway production of Hello, Dolly!).

Scandals of 1931 was Merman’s only non-book Broadway show. And it was one of her only ventures not a star vehicle fashioned just for her. She’d shared the spotlight with several other performers: not only Vallée, but also Ray Bolger and Ethel Barrymore Colt. Merman’s other big solo number in the revue was “(Ladies and Gentlemen) That’s Love,” a racy musical reply to Cole Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love?” That rarely heard song cited the mating habits of—among others—the toucan, the hippopotamus, and the married couple. That considered, Blackhurst’s selection of “Cherries” to represent Scandals in her Merman show seems the right choice.

After performances of Everything the Traffic Will Allow commenced, Blackhurst became aware that few audience members had ever before associated Merman with “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries.” With numerous Merman-signature-song candidates from Cole Porter, the Gershwins, and Irving Berlin, it’s no surprise “Cherries” was a hit that even the star herself seemed at times to neglect.

“It was not like she would go on a talk show and that was ever the song that was gonna play her on,” Blackhust says. “She had so many fantastic things that were hers, fair and square.”

The song’s lack of a strong connection with Merman made it easier for Blackhurst to employ it as a stand-alone title when she was called on to perform something outside the context of the show. Here she is singing it at a Sirius Radio Broadway event:

In Everything the Traffic Will Allow, Blackhurst would begin to strum her ukulele after the verse, as intro to the refrain. She did this in part because of the vintage sound it leant the song. But the uke’s sound also gave her rendition an informal, singing-around-the-campfire sort of feeling. A few bars of her whistling, late in the number, likewise add to this spirit of informality.

Everything the Traffic Will Allow was originally performed at Danny’s Skylight Room on Manhattan’s Restaurant Row, but it eventually moved to a makeshift theatrical venue at an upstairs space on Eighth Avenue in Manhattan that Blackhurst and company named “Upstairs at Jack Rose.” She notes that the space is now part of a Duane Reade pharmacy. “It was a gorgeous space. Now it’s just their cosmetics department.”

The show was enjoying a good run—then everything shifted.

“So, 9/11 happened. And—like everybody—we closed the show down for that weekend. Broadway did it, too. Everybody went on pause. And I think we stayed out longer than most shows. But, when we came back, at first I thought, ‘Oh, it’s so weird to…be singing Ethel Merman songs after this huge tragedy.’ And the firehouse that had lost so many of their firemen was right across the street. You could see it out the windows and it was all just so sad. But then I was like: ‘Well, Ethel Merman was a big hit during wartime. And entertainment is [meant] to help divert our attention and make sense of things’….”

When she first returned to the show, Blackhurst found herself choking up the moment she sang the opening line of Cherries: “People are queer….”

She attributes the rush of emotion to the very simplicity of the song. She believes that songs with understated emotional content like “Cherries” often tend to achieve poignancy better than elaborate musical statements of outrage and grief—the sort of songs “about loss and love and the towers burning” that are written with Sondheimian virtuosity. “Cherries” quickly became Blackhurst’s favorite song in her show.

“The artistry [of songs like “Cherries”] becomes clearer, the older I get…” she says. “The simplicity, the air that exists around the clear statement? You can put so much more into it, right? It can take on so much more meaning.”

I ask her whether she has any advice to a singer who’s thinking of performing the number. She doesn’t presume to offer anything specific.

“I would think any artist…who’s drawn to it would be able to give an incredible take on it. Because, again, it’s all there to put your stamp on…. I don’t think there’s any pitfall in it. I think it’s kind of a palate cleanser, a breath of fresh air…. And I would encourage it.…”

She pauses. Her voice goes stern, with a hint of threat:

“Just don’t do it with a ukulele!”

Another pause.

“I’m just kidding!… Maybe a trombone is the way to go!”

Then, wrapping up:

“No, I think it’s a lovely piece to have out there. So, I would say, ‘Have at it!’”

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.