Cabaret Setlist: “Take Care of This House” – Music by Leonard Bernstein, Lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Song #8 in this running series.

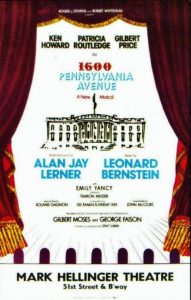

This installment of Cabaret Setlist is published on the day before what’s being called the most significant presidential election of our lifetimes. Wanting something pertinent to the occasion, we decided on a Broadway song first heard in 1976, the year of America’s bicentennial. “Take Care of This House” is from the score of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, a musical about occupants of the White House during its first 125 years.

By all accounts, the show was a colossal debacle. There had been great anticipation before its arrival, as it was composer Leonard Bernstein’s first new Broadway musical since 1957’s West Side Story. But after a chaotic try-out in Philadelphia, the new show played only 13 previews and 7 regular performances in New York.

By all accounts, the show was a colossal debacle. There had been great anticipation before its arrival, as it was composer Leonard Bernstein’s first new Broadway musical since 1957’s West Side Story. But after a chaotic try-out in Philadelphia, the new show played only 13 previews and 7 regular performances in New York.

Off with the Show

Bernstein and Alan Jay Lerner’s score was singled out by some observers as one of the few good things in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, but the chances that an unhappy production might leave a happier legacy grew slim when the decision was made not to record an original cast album. A revival of the show based on an early Lerner draft was assembled and directed by Erik Haagensen in 1992, but the show remains largely unknown by the general public. Recently, however—at a time when American democratic principles have found themselves in a precarious place—“Take Care of This House” has gained new attention.

The idea for the musical came from lyricist/librettist Lerner, who had been dismayed by the 1972 reelection of Richard Nixon. The show had not been conceived as a “bicentennial musical,” but the timing of the production prompted exactly that perception. Playgoers expecting an upbeat, flag-waving entertainment were understandably disappointed.

Lerner’s book dealt in great part with injustices done to Black Americans. Ken Howard and Patricia Routledge portrayed a succession of presidents and first ladies. The other major characters were Lud and Seena: African American servants played by Gilbert Price and Emily Yancy. Critics found Lerner’s treatment of race issues in the show patronizing and heavy-handed. “The show’s racial conscience bleeds like a seeping but superficial wound throughout,” wrote Clive Barnes in his rather snide New York Times review.

After original director Frank Corsaro was dismissed, two African American theatre-makers—Gilbert Moses and George Faison—were enlisted to restage the production, but this move didn’t help. Bernstein biographer Joan Peyser writes: “Moses told reporters that the show was too apologetic, that it set out a cynical hypothesis, and that it failed to celebrate the vitality and intellect that had made the country what it was.”

Later, though, at least one commentator noted that the libretto wasn’t as problematic as initially reported. Ken Mandelbaum, in his indispensable book Not Since Carrie: 40 Years of Broadway Musical Flops, remarked that, whatever other problems it had, “1600 was not pretentious or preachy.”

The show might actually work better now, in the era of Black Lives Matter. But, even if the pandemic magically goes away, I wouldn’t count on a revival of 1600 anytime soon.

Instructions for Householders

“Take Care of This House” was sung on Broadway by Howard, Routledge, and Guy Costley, who played the young Lud. (At this point in the show’s first act, Howard and Routledge were embodying John and Abigail Adams.) The song—which really belongs to Abigail— consists of instructions to Lud for the day-to-day care of the White House. Some of these directives are literal (“If bandits break in, sound the alarm”; “Be careful at night, check all the doors.”), but such lines, quite naturally, invite metaphorical interpretation: they’re not just a list of household maintenance chores but also rules for preserving the republic. John Charles Franceshina, in his textbook Music Theory Through Musical Theatre: Putting it Together, explains that Abigail’s direct instructions to Lud are set in one key, while the more “figurative” instructions are in a different one. For this song, the composer and lyricist seem to have been fully in sync.

Here’s a 1987 performance of Routledge singing the number in concert giving, maybe, some sense of the sound of her Broadway performance. Unfortunately, she skips the song’s introductory verse here: Listen to Routledge here.

After the collapse of 1600, Bernstein recycled some of the show’s melodies for other projects. “Take Care of This House,” meanwhile, found life outside the context of the show. In 1977, mezzo soprano Frederica von Stade performed it at the inauguration of Jimmy Carter. Here’s a studio recording of her version (again, without the introductory verse). Bernstein himself conducted on this track. Hear von Stade here.

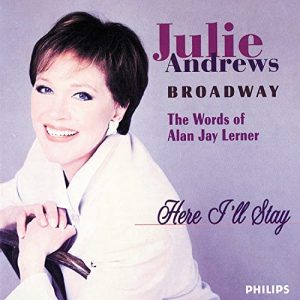

Throughout his career, the composer had always straddled the divide between classical and popular music. It seemed that, as the years passed, “House” was settling into the “serious music” camp. But then, in 1996, Julie Andrews made the song somewhat pop-ier when she included it in her album of songs with Lerner lyrics. In this version, you can finally sample Lerner and Bernstein’s introductory verse. Listen here.

Throughout his career, the composer had always straddled the divide between classical and popular music. It seemed that, as the years passed, “House” was settling into the “serious music” camp. But then, in 1996, Julie Andrews made the song somewhat pop-ier when she included it in her album of songs with Lerner lyrics. In this version, you can finally sample Lerner and Bernstein’s introductory verse. Listen here.

One year later, a concert version of 1600 called A White House Cantata was staged and recorded. With this version, audiences revisited the song’s theatrical roots. The characters of Abigail Adams (June Anderson) and young Lud (Victor Acquah) were resurrected for this presentation. Anderson and Acquah accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra.

The song found a new sheen in 2017 when Cynthia Erivo, Tony-winning star of the Broadway revival of The Color Purple, sang a graceful and tender version of it at the Kennedy Center, backed by the National Symphony Orchestra. It’s noteworthy that a song with strong American sensibilities was sung with such power and eloquence by a Briton like Erivo—though this had also been the case with the Julie Andrews recording. Listen to Erivo.

Bernstein and Lerner were both born in 1918. No surprise, then, that their careers and music were celebrated two years ago at various centenary events. At the same time, growing political apprehensions were making the song increasingly relevant in the midterm election year of 2018.

That year, right before the midterms, Barbra Streisand released her version of the song on her studio album Walls, a collection that expressed her concerns about the direction in which America was headed. Singing with steadiness and distilled passion, she includes the introductory verse, though with somewhat different lyrics from those heard on previously mentioned renditions. Streisand sings “Take Care of This House.”

That year, right before the midterms, Barbra Streisand released her version of the song on her studio album Walls, a collection that expressed her concerns about the direction in which America was headed. Singing with steadiness and distilled passion, she includes the introductory verse, though with somewhat different lyrics from those heard on previously mentioned renditions. Streisand sings “Take Care of This House.”

New York–based cabaret singer Darius de Haas finds the Streisand version—along with renditions by von Stade and Roberta Alexander—to be particularly inspiring: “Well, she’s Streisand. And she‘s always had a strong sense of justice and standing up for what is right. And I love that at—what?—76 years old when she recorded it, she still has that fire.”

“An Urgency that Spoke to These Times”

de Haas, a Bistro Award honoree, sang the song in 2018 for a “Lyrics and Lyricists” show at the 92nd Street Y, then again later that year in his Bernstein centenary show at 54 Below. He learned about the number from a particularly authoritative source: its composer’s daughter:

“Jamie Bernstein, who is a dear friend, suggested I learn it. She sang some of the lyrics to me, and it hooked me right in. [It had a] beautiful, compelling melody that has an urgency that spoke to these times.”

The singer finds the same “deeply felt humanity” in “House” that permeates the melodies of such other Bernstein songs as “Somewhere” and “Make Our Garden Grow.” And while he believes that the song has been especially apt during the last four years, its message seems universal:

“I think it works in terms of any administration, in that—when you are the leader of the free world—you must be accountable, honorable, decent, and mindful that you represent the ‘house,’ which is all of this country.”

The song’s melody is somewhat “range-y,” so de Haas advises singers who are interested in performing it to concentrate on pinpointing the key that works best for their particular vocal span. Further advice: “Learn it technically and then figure out what makes it personal to you. I mean, really, the song gives it all to you. Like a Sondheim song.”

Singer Richard Holbrook became familiar with the number when he was given the Andrews album as a birthday gift in 1995. He found it “haunting, but also “relevant and timeless.”

His first public performance of the song reaped mixed results. In 1996, he sang it in Orlando, Florida, in a Christmas show that was a benefit for homeless people. The number was part of medley he’d devised that also included “Build My House” (from Bernstein’s Peter Pan) and “God Help the Outcasts” by Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz, from the animated film The Hunchback of Notre Dame. He presented “Take Care of This House” as a song about a homeless person’s “ideal home,” rather than about the White House. Though the medley was well-received, he realized later that he’d made a mistake.

For his 2018 Lerner centenary show at Don’t Tell Mama, It’s Time for a Love Song: The Lyrics of Alan Jay Lerner, Holbrook wanted to feature the number. But did it qualify as a “love song”? Encouraged by friend and fellow performer Bob O’Hare, he paired it with the title song from Lerner’s Camelot (music by Frederick Loewe). He then linked the two songs with spoken narration about Lerner’s friendship with Bernstein and with John F. Kennedy, who was famously fond of Camelot—a show that, after Kennedy’s assassination, became a bittersweet metaphor for his presidency. (Lerner, Bernstein, and Kennedy had been students together at Harvard in the 1930s.)

This performance was a more satisfying experience for Holbrook than the show in Florida: “I felt I had successfully presented ‘Take Care of This House’ as a true and patriotic love song to America by Alan Jay Lerner.” Holbrook believes that the song’s message can be embraced by Americans of various political stripes.

Whose Dream Is It, Anyway?

One lyric in “Take Care of This House” puzzled me as I researched the song:

If someone makes off with our dream,

The dream will be yours.

The confounding word here is “our.” In context of the musical, is Abigail Adams, with the words “our dream,” referring only to the dream that she and her husband share? Or is she also including Lud—to whom she is speaking? (The “yours” in the second line suggests that the latter is not the case.)

Or, is it a race thing? Perhaps “our dream” refers to the dream of white, ruling-class Americans, while “yours” alludes to the dream of African Americans such as Lud.

Adding to the confusion is the fact that, while printed lyrics of the song seem consistently to write the phrase as “make off with our dream,” all of the singers included in clips in this article seem to sing either “make off with a dream” or “make off with the dream.” Was the lyric altered at some point over the decades? If so, why? How? And by whom?

In any event, the “altered” lyric seems contradictory:

If someone makes off with a dream,

The dream will be yours.

What? When something is stolen, how can it still be there? Is the dream Lerner writes of some kind of perpetually regenerating phenomenon, replenishing itself time and again, like a magical hydra head?

Maybe that’s it. Maybe the lyric describes not a contradiction but a paradox.

Could it be that the American Dream is resilient beyond all our expectations? Could it be that, no matter what happens on November 3, 2020, the dream will still be there for those who refuse, with brave persistence, to relinquish it to “bandits”—or to thugs carrying tiki torches?

I hope it doesn’t come to that, but it’s something worth keeping in mind.

Meanwhile, let’s close with a stirring new Zoom-era video of the song, featuring pianist Lara Downes, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Bistro Awards 2019 Lifetime Achievement winner Judy Collins, and a host of diverse American singers and musicians:

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.

Mark,

I just read your 1600 article and I have to respond. The published lyric to Take Care of This House has “a” not “our” and I think the “a” in this context means “any.” (If someone destroys any of its statutes, the collective “you” suffers.). I saw the show three times in New York and I was never confused by this. I have also never seen it published as “our” including in The Complete Lyrics of Alan Jay Lerner that was published a few years ago. That seems to me to be a singer’s choice and nothing to do with Lerner. Poor Alan Jay. Everybody is always fixing his work, forgetting that first and foremost he was a poet.

And just to be extra picky, 1600 also played Washington DC after Philladelphia and the subsidiary characters are named Lud and Seena (not Leena.). The story also covered the first 125 years in the White House, from George Washington to Teddy Roosevelt, not just the 19th century. The White House Cantata was created because Bernstein, (who was responsible for their being no cast album,… he had it in his contract that the show had to play TWO weeks or he could pull the plug on it… which he did.) did not want the work to be performed with the book ever again. Hence, the cantata creation. Regarding the original production, Patricia Routledge stopped the show at one of the performances I attended and I have never experienced that before or since. She had left the stage, the set had changed, the new actors were already in place and the audience would not let the show continue until she came out and took another bow. In short, there was more than enough up there on that stage to merit a run. I’ve never forgotten it and, hopefully, never will.

Hope you’re well.

Barry Kleinbort

Thanks, Barry Kleinbort, for your comments, corrections, and clarifications. I appreciate them. We’ve changed the character’s name from “Leena” to “Seena” and noted that the musical covered late 18th century presidencies as well as 19th century ones.

I found numerous instances of “our dream” instead of “a dream,” including in Clive Barnes’s review of the original production and Adam Gopnik’s recent New Yorker article. But those do appear to be in error, and I regret adding to the confusion.

I still find the lyric “If someone makes off with a dream, / The dream will be yours.” to be cryptic–but that is not necessarily a bad thing.

And thanks for mentioning Patricia Routledge’s show-stopping performance. There is a live audio recording of her big song “Duet for One” available on YouTube. You are lucky to have been there to have experienced it in person. Thanks again.

Nice piece, Mark. Thanks for writing it. The word in the lyric is “a,” not “our,” and I have always taken it to mean the American dream, which Abigail is making a point of including Lud in. The verse that Julie Andrews recorded was discovered by me in pencil sketch when reconstructing the show. It wasn’t used on stage because Lerner got the idea to start the verse with a comic reprise of “On Ten Square Miles by the Potomac River,” which then segues into the second half of the original verse. Using the whole verse would have made the song lopsided. Still, it’s a lovely verse as originally written, and the Bernstein estate agreed, providing it to Ms. Andrews for her premiere recording of it.

I must, however, correct something that Barry said in his comment. The cantata was not created because Bernstein never wanted the book to be performed again. He didn’t want what ended up on Broadway to be performed again. In the mid-80s, Bernstein returned to the show and asked Lerner for permission to hire a new book and lyrics writer. Bernstein wanted to return to the “gypsy run-through” version of the show, as he and Lerner had originally conceived it, and rewrite from there. Lerner gave Bernstein the right to hire a new writer (I’ve seen the letter), though he asked for a crack at writing any new lyrics. His lung cancer diagnosis quickly made that possibility moot. Bernstein approached Gore Vidal to be the new writer, but he declined. The 1992 production that I reconstructed and directed was based on the version of the script that opened in Philadelphia, though I put back some musical material that had been cut in rehearsal. It was generated by the Bernstein estate because Bernstein had wanted to try to fix the show.

The production was initially simply a workshop, but that went so well that Roger Stevens, one of the original producers, said that if Indiana U. would do the show as a production in its summer musical slot, he would present that production at the Kennedy Center. IU did, Stevens followed through, and the show was pretty successful with audiences and critics, which convinced the Bernstein estate to hire me to do a rewrite.

I did, and that version was given a concert reading in Manhattan in 1995, generating production interest from three major regional theatres. Unfortunately, two of the three administrators of the Bernstein estate refused to even attend the reading, and then they voted to create the cantata rather than let the show go forward on stage. It was those two people who decided they didn’t want 1600 to live again on stage, not Leonard Bernstein. I was asked to create the cantata and refused, precisely because a cantata was not what either author, Bernstein or Lerner, had ever intended. The cantata someone did make removed almost all of the overtly political material from the show, which is what happened with the original production as well, a decision that Bernstein was firmly against originally (I’ve seen the many letters) and, I think, would have been against once more.

Please don’t say that Bernstein’s wishes were being honored in creating the cantata. He wrote a political piece, he wanted it to be a political piece, and the cantata gutted the political content.

Thanks so much, Erik, for your feedback. I know that you’ve taken a big part in the “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” saga, and I greatly appreciate your reading the article and contributing to the discussion.

Good to hear from you! Be well,

m.