Cabaret Setlist: “When October Goes” – Music by Barry Manilow, lyrics by Johnny Mercer

Repertoire for the Once and Future American Songbook

Song #13 in this running series

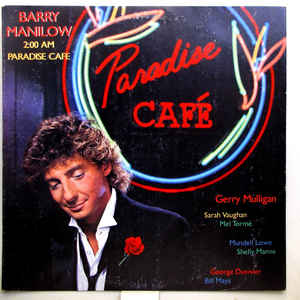

The lucky thirteenth installment of Cabaret Setlist centers on “When October Goes,” a short, bittersweet, and evocative ballad of love and loss. The song, which debuted in 1984, has gradually come into its own as a modern standard. It has a most unusual pedigree. Its words were written by one of the most beloved lyricists of the mid–20th century: Johnny Mercer. Its melody was composed by pop vocalist Barry Manilow about eight years after Mercer’s death. The singing star had spent the earliest years of his career in New York City cabaret venues, most famously as pianist for rising star Bette Midler. Manilow first performed “When October Goes” on his album 2:00 AM Paradise Café, a suite of original, jazz-inflected melodies that featured guest performances by Sarah Vaughan and Mel Tormé. Listen to Manilow here.

The lucky thirteenth installment of Cabaret Setlist centers on “When October Goes,” a short, bittersweet, and evocative ballad of love and loss. The song, which debuted in 1984, has gradually come into its own as a modern standard. It has a most unusual pedigree. Its words were written by one of the most beloved lyricists of the mid–20th century: Johnny Mercer. Its melody was composed by pop vocalist Barry Manilow about eight years after Mercer’s death. The singing star had spent the earliest years of his career in New York City cabaret venues, most famously as pianist for rising star Bette Midler. Manilow first performed “When October Goes” on his album 2:00 AM Paradise Café, a suite of original, jazz-inflected melodies that featured guest performances by Sarah Vaughan and Mel Tormé. Listen to Manilow here.

Here’s the abridged story of how Manilow came to set Mercer’s lyric for the song: A few years after the lyricist’s death, his widow, Ginger Mercer, arranged to send some unfinished lyrics to Manilow. Toward the end of his life, her husband had become fond of the younger man’s music. She wondered—would he want to try his hand at setting some of Johnny’s unfinished pieces? Manilow was game, and he soon set “When October Goes.” The number became the centerpiece of the Paradise Café album, which climbed to #28 on the Billboard 200 chart and eventually went Platinum.

Different versions of the story behind the song can be found online, but as I begin studying the song, I wish for more details. Eventually they will come. But I’ll get to that in a bit.

Snowflakes and Chimney Smoke

Much of the song’s appeal resides in its simplicity. “When October Goes” has no introductory verse. The main melody centers around a series of phrases of six syllables that gently rise and then softly fall, as if they are reaching for something that’s not quite accessible. On the fourth phrase, the notes end in an ascension rather than a drop, creating a hint of hope, perhaps. The melodic line takes different turns as the tune progresses, but the song has no bridge to speak of. The melody seems to come to an end. But then a coda is heard—providing a release and a strange kind of benediction—a mere three lines long.

As for the lyrical content, it is similarly uncomplicated. At the top of the song, the protagonist, communicating in present tense, is focused on the surrounding autumnal landscape, both natural and human-made: the year’s first snowflakes, chimneys with smoke curling from them. The most striking thing to me about the lyric is that it begins with a conjunction: “And…” This suggests that the protagonist is in the middle of a thought or a conversation or a daydream before the first note is sung. “And when October goes / The snow begins to fly.” The question of what may have immediately preceded that thought gives the song a hint of mystery, right from the beginning.

The character’s attention soon moves upward from smoky roofs to distant airplanes passing overhead. Then, immediately, the focus shifts back to earth, to a group of children scurrying home as night falls. Their joyful enthusiasm for life inspires memories of the protagonist’s own past: “Oh, for the fun of them, / When I was one of them.” The character’s nostalgia finally touches on a dream of embracing a loved one. This is the one point in the song when the listener is addressed as “you”: “…You are in my arms / To share the happy years.” This “you” is likely a romantic partner, but there is nothing in the song suggesting it couldn’t be a parent, a child, or a dear friend. The protagonist fights back tears before the coda, in which a kind of truce is reached with both the coming winter and the human loss that winter signifies.

The Long and Short of It

It wasn’t long after the success of Paradise Café that “When October Goes” prompted some notable covers.

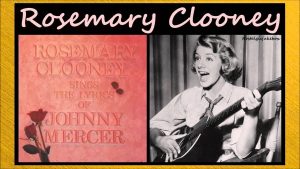

Rosemary Clooney’s 1987 take is steady and straightforward. She sings the number without vocal frills. Clooney’s protagonist pours out her heart—broken though it may be—without flinching. In this live performance, there’s often a slight smile, both on her face and in her voice.

Rosemary Clooney’s 1987 take is steady and straightforward. She sings the number without vocal frills. Clooney’s protagonist pours out her heart—broken though it may be—without flinching. In this live performance, there’s often a slight smile, both on her face and in her voice.

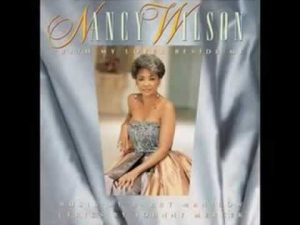

By 1991, Manilow had set several other lyrics from among those sent to him by Ginger Mercer. They were showcased in Nancy Wilson’s album With My Lover Beside Me, which Manilow produced. “When October Goes” is a highlight of the collection.

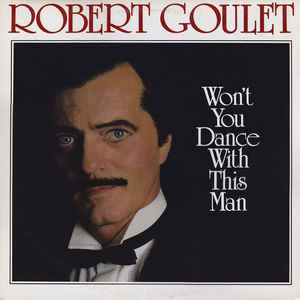

The robust baritone of the late Robert Goulet makes for another very pleasing rendition. Goulet’s powerful singing is accompanied by an almost samba-ish soft-rock styling that flares into something more flamboyant at key moments. Yes, the arrangement on this 1997 recording sounds a bit dated now. But this is a song about looking back, so that’s, maybe, not such a problem.

The robust baritone of the late Robert Goulet makes for another very pleasing rendition. Goulet’s powerful singing is accompanied by an almost samba-ish soft-rock styling that flares into something more flamboyant at key moments. Yes, the arrangement on this 1997 recording sounds a bit dated now. But this is a song about looking back, so that’s, maybe, not such a problem.

A 2003 recording by jazz performer Diane Schuur employs a lavish orchestration to underscore the vocalist’s avid throb. Schuur, near the end of the cut, includes the sort of vocal embellishments that the serene Clooney avoids, but her version is equally earnest and strong. And there’s something about those hard “R”s of Schuur’s that seems just right for this song. I find her version assured and radiant.

One of the facets of the song that vocalists need to deal with is its brevity. “When October Goes” will seem appropriately succinct to some singers and a little too spare for others. I wonder whether Mercer planned additional content that he didn’t live to include. Did the “And” at the beginning of the lyric mean he’d considered an introductory verse—something he never got around to writing? In order to make the number seem longer and fuller, singers can slow the pace, of course, or repeat parts of the song. Inserting an instrumental break, perhaps a rather long one, can also prolong the spell that the song casts.

Or…the singer can mash “When October Goes” up with another song or songs. According to the Secondhand Songs website, this title has been paired in recordings with “My Favorite Year” (Karen Gottlieb, Michele Brourman) and “Two for the Road” (Henry Mancini, Leslie Bricusse). But the song most often paired or blended with it is “Autumn Leaves,” which also happens to have a Mercer lyric. The English-language iteration was adapted from 1945’s “Les Feuilles mortes,” composed by Joseph Kosma, with a French lyric by Jacques Prévert. The song was first heard in the 1946 film Les Portes de la nuit (Gates of the Night).

The late Nancy LaMott was one of the first singers to put the two songs together (in 1992). Listening to her version (with an arrangement by Christopher Marlowe), you’ll understand the impulse for pairing the numbers. Beyond the Mercer connection and the shared autumnal theme, the songs have musical commonalities. “Autumn Leaves,” in its chorus, begins with short lines (of four and five syllables) that rise and fall in a manner similar to the phrases of “When October Goes.” Note that LaMott doesn’t interweave these songs. She presents them sequentially. It makes sense to start with “Autumn Leaves,” which describes a time during early fall when leaves “of red and gold” are still falling. “When October Goes” centers on a slightly later period, when drifting leaves have given way to blowing snow.

The late Nancy LaMott was one of the first singers to put the two songs together (in 1992). Listening to her version (with an arrangement by Christopher Marlowe), you’ll understand the impulse for pairing the numbers. Beyond the Mercer connection and the shared autumnal theme, the songs have musical commonalities. “Autumn Leaves,” in its chorus, begins with short lines (of four and five syllables) that rise and fall in a manner similar to the phrases of “When October Goes.” Note that LaMott doesn’t interweave these songs. She presents them sequentially. It makes sense to start with “Autumn Leaves,” which describes a time during early fall when leaves “of red and gold” are still falling. “When October Goes” centers on a slightly later period, when drifting leaves have given way to blowing snow.

“Intimate and Introspective”

As I continue my examination of “When October Goes,” I seek out a few contemporary cabaret singers who have recorded or otherwise performed it. Chicago-based vocalist Megon McDonough sang it as the title track of a 1991 album, When October Goes—Autumn Love Songs, which included tracks by various performers. The project was helmed by Christine Lavin, who had sung with McDonough in the group “Four Bitchin’ Babes.”

McDonough has long been a Manilow fan, but she came to know this song through the Clooney version. “There are just some singers who have ‘it’ and she was one of them,” she says. McDonough recorded “When October Goes” with pianist, arranger, and producer Steve Rashid (a frequent collaborator of hers) at the Woodside Avenue Music studios in Evanston, Illinois.

The atmosphere of the Woodside studio, which had recently moved to the basement of an old mansion—with dark wood paneling and “a great acoustic baby grand”—added to the magic of the session. There was a photo of Rashid from his college days, posing with Duke Ellington. “Every incarnation of Woodside Avenue [Music] has had the same warmth and genuine ‘music comes first’ vibe,” McDonough says.

“Certain songs are like flying,” she continues. “But a song like ‘When October Goes’ is so intimate and introspective that I went back [in my mind] to… a rooftop in New York City, where I lived in the 1980s… No matter how old you get, you carry love loss in your DNA, like a soul tattoo. I remember being so quiet and available for that song as well as [for] the muse. The challenge was [not to just] sing it, but to tell the person you’re singing it to what’s in your heart.”

McDonough was not bothered by the relative shortness of the song. “I didn’t want to stop singing it…” she admits. “But…the brevity of it adds to the longing, maybe.” Hear McDonough here.

Bistro Award recipient Lisa Viggiano performed the song in 2002, when she was living in the San Francisco Bay area, at a gala show for the Richmond/Ermet Aid Foundation, which provides funding for AIDS organizations, homeless youth, and anti-hunger programs. Musical director for this show was Ron Abel. Viggiano’s version casts “When October Goes” in a more dramatic, belting style than most other renditions we’ve encountered.

“When I sing this exquisite piece,” she says, “I always think of conversations with my late Grandmother Mullane towards the end of her life. She would share lovely memories as well as words about the loneliness she felt as her loved ones and friends had passed on before her. I imagine that this lyric would be similar to the thoughts that she would have as she walked her dog around the neighborhood or while she would gaze outside from her window.”

Note that this arrangement includes the “Autumn Leaves” theme in non-vocal passages, although Viggiano sings only “When October Goes” itself. Listen to it here.

A Gallic Tinge

The version that two-time Bistro Awards honoree Amy Beth Williams created for a 2015 Don’t Tell Mama show, Crazy to Love You, is considerably more complex than some of the previously mentioned renditions.

Before plans for the show gelled (and before director Tanya Moberly came on board), Williams, over a period of several months, worked on a variety of material with musical director Daryl Kojak. Williams was a fan of Manilow’s (and especially his hit “Could It Be Magic,” a recording she can recall singing while listening on her Walkman). She had latched onto “When October Goes” during “an incredibly intense relationship change.”

Unaware of the Nancy LaMott medley, she decided she wanted to perform the Mercer/Manilow song in tandem with “Autumn Leaves”—or, rather, with its French-language predecessor, “Les Feuilles mortes.” She considered “When October Goes” to be an art song or a tone poem and “Les Feuilles mortes” to be “a pop tune of a certain ilk.” Williams and Kojak created a presentation that wove the songs together, moving back and forth between the two melodies.

At one point during later rehearsals, they shared material from the upcoming show with acclaimed cabaret performer Marilyn Maye. Her response to the medley, Williams remembers, was quick and to the point: “Darling, nobody speaks French…. We need some English in here. What do these words mean?”

Williams and Kojak heeded Maye’s advice and simplified the arrangement. They reduced the medley’s French content. They eliminated some of the back-and-forth switches between the two songs. At one point in the song, Williams added a short passage of Mercer’s English lyric from “Autumn Leaves.” And, during an instrumental interlude, she spoke an English translation of some of Jacques Prévert’s very dark French lyrics. (Mercer’s English words for the Joseph Kosma’s melody were not a direct translation of Prévert’s original lyrics, nor were they quite as bleak.) At one point Williams even sang a bit of “When October Goes” in French, switching in a lyric of Prévert’s that happened to scan with Manilow’s melody.

“It’s that French thing,” Williams says of the arrangement. “You talk, you sing, you reprise it. You talk, you sing, and it ends. And it’s very sad.”

Adding to the melancholy of the arrangement was the artistry of accordionist Will Holshouser.

“That accordion, to me, is just delicious—and Will is wonderful,” says Williams. “I loved having that. I could do it without [the accordion], but that adds just—such beauty. If I was gonna do it in a show again, I’d want the accordion with it.” Click to listen to Williams.

“It Was Written Before I Got There”

I’m about to wrap up my examination of “When October Goes” when I receive a response to an email I’ve sent earlier. Barry Manilow has agreed to speak with me about his song. To say that this news makes my day is an understatement. Early on a February afternoon, I receive the phone call from Palm Springs. After explaining exactly what I want to talk about, I ask Manilow about having received those lyrics from Ginger Mercer more than 35 years ago.

“It’s a very short story…” he says. “Back in the early eighties, I guess, I got a phone call from my record company. This was after Johnny Mercer had passed away. Ginger Mercer…his widow…had discovered a stack of lyrics that he had written—that nobody had ever put music to. They weren’t all completed, and some of them were in his handwriting and some were typewritten. She didn’t know what to do with them, and she liked my work and asked my record company whether they could get [them] to me.”

Manilow told the record company to send the lyrics his way. He still has them—along with the manila envelope in which they had arrived. He recalls first looking over the lyrics in that packet:

“Some of them sounded like they should have been in Broadway musicals…. They looked like they were coming from a [theatrical] situation. They were ‘cowboy’ kind of lyrics, and I don’t know what situations they were in, but they weren’t all pop songs. But some of them were. They were…lyrics that sounded like a Johnny Mercer pop song that any one of those great composers would have put melodies to.

“And one of them was ‘When October Goes.’ That was the first one that I pulled out. And I stuck it on the piano, and I hit the cassette machine. I… hit the piano keys and I read the lyric and I sang the song. I shut the cassette machine off, and that was it…. I never went back. I never had to fix it up. I never had to change anything. It was just right there. It was written before I got there. I don’t know how something like that happens. Maybe Johnny was sitting on my shoulder and showing me what he wanted.”

Whether or not something paranormal had occurred, Manilow was happy with his composition. He added “When October Goes” to the stack of songs he planned to use on his upcoming album.

“When we recorded it, the band knew that there was something going on with that song. I had a second pianist there—I played piano, but I had a real jazz pianist, Bill Mays. And he looked up and he said, ‘Whoa, this is big.’ And…it went on the album, and it was always the standout cut from the Paradise Café album.”

Manilow describes that final recording in detail in his liner notes for 2:00 AM Paradise Café.

That events of that date were, in their own way, as serendipitous as his randomly picking up the “When October Goes” lyric from that stack of papers in Ginger Mercer’s manila envelope. He had taped the songs, along with their musical connective tissue, during the last couple of studio dates, but at the very end of the final session, he decided to try recording the entire album in a single take.

“They started to roll the tape—it was tape at the time. We started at the beginning and we ended at the end. And that’s the album. It was just one long take. We had rehearsed for a week, and [the musicians] knew these songs in their bones. It was just thrilling.”

He claims that the Paradise Café album changed his musical life:

“That was the moment I said, “OK, this is why I’m in the music business. And I can’t go back to doing ‘I Write the Songs.’ I can’t do it anymore. And then I left Arista Records and Clive [Davis]—with his brilliant singles and charts and bullets and all that stuff I’d been doing for 10 years. That changed everything.”

Of course, Manilow didn’t abandon his pop career altogether. Certainly, he has continued to sing “I Write the Songs” over the decades. But he’d come to the awareness that there were other musical options to be considered.

Of the 35 or 40 Mercer lyrics that Manilow received, he has found melodies for about 15. Inspiration didn’t come quite as readily to him for these other numbers as it did for “When October Goes.” In addition to composing music for songs on the Nancy Wilson album, Manilow set a Christmas lyric of Mercer’s, “I Guess There Ain’t No Santa Claus.” He included that jocular song, about being lovelorn during the Christmas season, on his first holiday album.

Generally, he believes that the melodies that come quickly to him tend to be more successful. “I think the listener can hear the struggle. I find that when I don’t have to struggle, then I know I’ve got something…. ‘Copacabana’ was the same thing. Bruce [Sussman] and Jack [Feldman] gave me the lyric, and I just played it down, and that was it.’”

In 2000, Manilow made a couple of New York City appearances that commemorated his connection with the cabaret community. He showed up at the annual Cabaret Convention, produced by the Mabel Mercer Foundation, on an evening when the artistry of a Mercer named Johnny was celebrated. And he appeared at the Manhattan Association of Cabaret Awards, where he was presented with that year’s Board of Directors Award.

“That was great…” he says, “Those people—with their stories and their medleys and their humor and their passion—I took everything I learned from them and put it into the pop world. And I think that really made a difference with my career. ’Cause nobody was doing that. There were no guys that were doing that. Everybody was either rock and roll or just jumpin’ around the stage. I was doing what [cabaret performers] were doing: talking to the audience, kibitzing with them, doing medleys…. These people were filled with ideas, and I just loved working with them. And it was an honor to get an award from them and to see them all—from Jamie deRoy to Jane Scheckter. I’d played for all of them, and they were my friends.”

When I let him know that “When October Goes” remains popular in the cabaret community, he is pleased. “It makes me feel great that those people that I admired so much discovered a song that I wrote.”

I ask him if he has any advice for singers thinking about performing the number.

“Warm up—there’s a high note at the end,” he jokes. But then he adds:

“Just tell the truth. Don’t worry about the notes, just tell the truth. And it’ll work.”

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.

Wonderful article about one of my favorite songs and artist. On New Year’s Eve morning, 1985, as I was driving on Beverly Blvd in West Hollywood, California, with 2 am Paradise Cafe playing on my tape cassette , I spotted Barry Manilow window shopping near the Beverly Center. I pulled my car over, rolled down the window, and told him I was listening to his album with my favorite song And When October Goes. He came over to the window and I wished him a happy New Year. One of my fondest memories. The rendition that had always resonated with me is Rosemary Clooney’s version: so simple, no drama, and heart rending. Thank you for allowing me to share this memory.

Just beautiful to stumble upon as I’m preparing to sing one of my favorite songs in a Zoom jam as october goes..

The passage about Manilow sitting down with Mercer on his shoulder made me weep. The beauty and spirit of music is indescribable.

Thank you for writing all this!!

ps. my wonderful, terribly missed mentor, Rebecca Parris also recorded When October Goes. She taught me it.

Best regards,

Louise