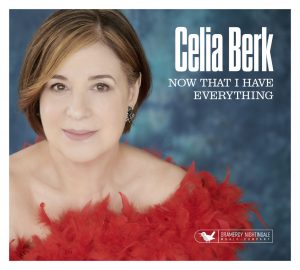

CD Review: Celia Berk’s “Now That I Have Everything”

A wondrous singer, Celia Berk provides the perfect autumn album with her new CD, Now That I Have Everything. Her handsome voice emits the warm beauty of fall colors, deep browns, rich reds, golden yellows, and bold orange. And her album’s beguiling musical selections, reflecting the many facets of romantic love, are rendered from a seasoned perspective, in the low, confident voice of a mature woman, with resolute diction and daring musicality. But it’s not solely Berk’s authoritative vocals that make this such a special CD. Music buffs of all stripes will value its unearthing of largely unknown songs by well-known composers. And jazz aficionados, in particular, will appreciate its arranger/pianist Tedd Firth’s choice to revive the King Cole Trio format—ensconcing Berk’s singing amid intricate piano, bass, and guitar arrangements that eschew the inclusion of a conventional drum set.

About half of the CD’s enthralling arrangements are co-credited to Firth with Sean Gough, the pianist with whom Berk collaborated in developing much of this material for her 2019 cabaret show, Comes Love. Beyond their noteworthy nod to the distinctive sound of the 1940s trio led by jazz pianist Nat King Cole, the arrangements assist Berk immeasurably in expressing the dramatic content of the song lyrics. For example, while she sings the album’s flirtatious opener, “How Are Ya’ Fixed For Love?” (James Van Heusen/Sammy Cahn), with the forthright matter-of-factness of a woman who knows what she’s looking for and is not afraid to ask for it, the more youthful, coy, come-hither qualities of flirty-ness are supplied by teasing piano and guitar passages. The CD’s versatile guitarist, Matt Munisteri, figures even more prominently in conveying the drama of “It Happens Everyday,” a break-up song by Carly Simon. While Berk phrases the lyrics with elegant smoothness, drawing long connected lines of melody filled with rich emotion, Munisteri takes on the role of her soon-to-be-ex-lover and responds with twangy guitar statements, making for an appropriately contrasting long-good-bye conversation.

About half of the CD’s enthralling arrangements are co-credited to Firth with Sean Gough, the pianist with whom Berk collaborated in developing much of this material for her 2019 cabaret show, Comes Love. Beyond their noteworthy nod to the distinctive sound of the 1940s trio led by jazz pianist Nat King Cole, the arrangements assist Berk immeasurably in expressing the dramatic content of the song lyrics. For example, while she sings the album’s flirtatious opener, “How Are Ya’ Fixed For Love?” (James Van Heusen/Sammy Cahn), with the forthright matter-of-factness of a woman who knows what she’s looking for and is not afraid to ask for it, the more youthful, coy, come-hither qualities of flirty-ness are supplied by teasing piano and guitar passages. The CD’s versatile guitarist, Matt Munisteri, figures even more prominently in conveying the drama of “It Happens Everyday,” a break-up song by Carly Simon. While Berk phrases the lyrics with elegant smoothness, drawing long connected lines of melody filled with rich emotion, Munisteri takes on the role of her soon-to-be-ex-lover and responds with twangy guitar statements, making for an appropriately contrasting long-good-bye conversation.

The album’s Song Notes (accessed at celiaberk.com/now-that-I-have-everything) reveal that it was Berk’s idea to have Munisteri think of himself as the “boy” figure speaking to the “girl” in the song’s narrative. Yet that’s just one piece of the picture. As we read on through the Notes, we learn that, in addition to her singing, Berk contributed significantly to the conceptualization of this enchanting album, providing research, structure, and arrangement ideas throughout. The album offers two remarkably blended pairings, both of which were Berk’s idea, and now that we’ve heard them, in both cases, it’s hard to imagine either song being sung without the other. In the sexy mash-up “Moonburn” (Hoagy Carmichael and Edward Heyman)/”The Late, Late Show” (Murray Berlin [pseudonym for Dave Cavanaugh]/Roy Alfred), Berk scrapes the bottom of her range to tickle us with her signature intimate singing style, described in Will Friedwald’s liner notes as like a “dialogue between two close friends.” She pours the songs’ hot sentiments into your ear, as if you, and you alone, are right there under the covers with her. The other pairing matches one of the album’s few familiar songs, “The Shadow of Your Smile” (Johnny Mandel/Paul Francis Webster), with Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “Dreamer” (Vivo Sonhando). Propelled by its soft Latin rhythms, the result is dreamy, indeed.

Another of Berk’s intriguing arrangement concepts was the challenging choice to sing “Right as the Rain” (Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg) with just David Finck on bass as her accompaniment. While Finck’s plucked bass notes lend buoyancy, Berk is on her own to conjure the melody, rhythms, and mood of this love ballad from the 1944 Broadway musical Bloomer Girl. While I might have preferred a lusher arrangement, Berk’s version is undeniably interesting and certainly suitable for the song’s unsentimental lyrics.

Other highlights of the album include an impressive jazz arrangement of the 1931 standard “Sweet and Lovely” (Gus Arnheim, Charles N. Daniels, Harry Tobias), which integrates Berk’s vocals so tightly within the instrumental parts that she crosses over that line from “cabaret singer doing jazz” to “authentic jazz artist.” And “Overjoyed” (Stevie Wonder) is particularly appealing in the way its bossa nova arrangement and Berk’s gentle vocals differ from the slow tempos and weighty qualities of much of the rest of the album.

Berk displays persuasive acting chops in her no-nonsense performance of the closing track “Now That I Have Everything” (Ervin Drake), and while we Broadway fans may be used to a brasher interpretation of “With Every Breath I Take” (Cy Coleman/David Zippel), from the 1989 musical City of Angels, the intentional fragility Berk brings to the number is highly affecting. Yet the song most likely to excite theatre folk is “Comes Love” (Lew Brown, Charlie Tobias, Sam Stept), which Berk sings in an almost “belt-y” style, at times. She bites into the lyrics, has literal fun making a squealing sound out of the words “a mouse-y,” glides through pitches as she sings “sliding,” and ends by diving down to the C below Middle C, as if in imitation of an operatic basso profundo. Friedwald thinks “singer” is too impersonal a term to describe Berk. I think it’s too limited. As her album title claims, she surely does have everything.

***

About the Author

Lisa Jo Sagolla is the author of "The Girl Who Fell Down: A Biography of Joan McCracken" and "Rock ‘n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s." A choreographer, critic, and historian, she has written for Back Stage, American Theatre, Film Journal International, and numerous other popular publications, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals. An adjunct professor at Columbia University and Rutgers, she is currently researching a book on the influence of Pennsylvania’s Bucks County on America’s musical theatre.