Now You’ll Know: Rick Pender’s “The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia”

All right, so you’ve read pretty much everything that’s ever been written about American songwriter Stephen Sondheim, and you’re thinking: Why on earth would I need to have something called The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia?

Let’s put your Sondheim knowledge to the test with three questions (no Googling allowed!):

- Who was originally hired to play Fredrik in the film version of A Little Night Music?

- What’s the only song for which Sondheim set the words of another writer to music?

- Within a Sondheim context, what’s the meaning of the name “Blackwings”?

If you knew that actor Peter Finch was the first choice to play cinematic Fredrik, that “Fear No More” (from The Frogs) has a lyric by William Shakespeare, and that “Blackwings” are Sondheim’s favorite number-two pencils, then congratulations! You may well be Stephen Sondheim.

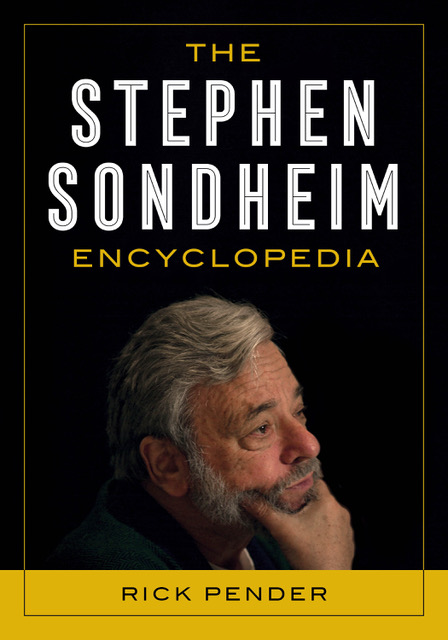

If not, maybe you could use a copy of Rick Pender’s just-released, 652-page guide to all things in the Sondheim sphere.

If not, maybe you could use a copy of Rick Pender’s just-released, 652-page guide to all things in the Sondheim sphere.

Recently, I had a chance to chat with Pender over the phone about this impressive new volume, published on April 15 by Rowman & Littlefield. Pender and his wife reside in Cincinnati, OH, where he has worked as a theatre critic and arts journalist for many years. The author also served for 12 years as managing editor of The Sondheim Review, a quarterly journal dedicated to the works and career of the composer/lyricist.

Rolling Along

Pender’s fascination with Sondheim began early. When he was about 13, he bought the soundtrack of the movie version of West Side Story, for which Sondheim had written the lyrics for Leonard Bernstein’s music.

“Of course, the movie was a big hit, and I was excited about that,” he recalls. “But it was the lyrics that really captured me. I didn’t know who Stephen Sondheim was. And most of the world didn’t know who Stephen Sondheim was back in the early ’60s. He was a pretty young guy, just starting out. But that’s where I first caught a whiff of this amazing talent.”

Pender followed the Sondheim career as it flourished. Then, a couple decades later, he knew he would be laid up for some time, following surgery. In advance of this, he visited the public library, where he borrowed several recordings to enjoy during his downtime, including a three-disc set called A Collector’s Sondheim (1985). It included songs from lesser-known scores from such shows as The Frogs, Anyone Can Whistle, and the TV musical Evening Primrose. “I was pretty much reeled in—hook, line, and sinker—at that point.”

In the 1990s, Pender was delighted to discover The Sondheim Review. And, in 1999, when Cincinnati Playhouse staged a version of Sweeney Todd in which the role of Mrs. Lovett was played by Pamela Myers (who had created the role of Marta in the original Broadway iteration of Company), Pender volunteered to review the production for the magazine. He was granted that assignment, and soon he was contributing regularly to the magazine. By the time he was asked to assume the publication’s managing editor role, in 2004, much of his working life was tied to things Sondheim.

In the 1990s, Pender was delighted to discover The Sondheim Review. And, in 1999, when Cincinnati Playhouse staged a version of Sweeney Todd in which the role of Mrs. Lovett was played by Pamela Myers (who had created the role of Marta in the original Broadway iteration of Company), Pender volunteered to review the production for the magazine. He was granted that assignment, and soon he was contributing regularly to the magazine. By the time he was asked to assume the publication’s managing editor role, in 2004, much of his working life was tied to things Sondheim.

After The Sondheim Review ceased publication in 2016, Pender tried to extend coverage of pertinent news and events with a subscription-based website called EverythingSondheim.org. Unfortunately, too few subscribers signed on to make this undertaking a go. The site was eventually sold to Signature Theater in Arlington, VA, with which it still exists as an online publication. Pender is not directly involved with the site, but he occasionally contributes articles to it.

The Gamut, A to Z

When Pender was approached by Rowman and Littlefield in 2018 about the encyclopedia, he was startled and intimidated by the amount of work involved.

“I said, ‘Sure I’d be interested in being part of that.’ They said, ‘Well, we’re interested in your being more than part of it. We’d like you to write it.’… They sent me a contract that asked for 300,000 words. I thought, ‘Holy mackerel, that’s a lot of words.’ But Sondheim certainly deserves them.”

Over the next two years, Pender generated 131 separate articles, including a long biographical entry on Sondheim himself. His first order of business was to generate a list of essential articles. His original list included nearly 200 articles, but the publishers asked him to pare it down somewhat.

“All 18 of Sondheim’s major shows are included, and many of his minor works and unfinished works, and that sort of thing,” Pender explains. “And then there’s a lot of material about directors he worked with, designers, his writers, actors who originated certain roles, and so on.”

Each of the articles about individual musicals in the Sondheim canon spans several pages. Pender concentrated on finishing those entries first. However, he would occasionally take a break from them to knock out a shorter article. For instance, he knew that, because of the book’s alphabetized format, the article on theatre director George Abbott would be the encyclopedia’s very first entry. (Abbott was the director of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, the first of Sondheim’s Broadway shows for which he was both lyricist and composer). The Abbott entry became one of the first of the shorter articles Pender tackled.

Largely because of his work on The Sondheim Review, Pender had little need to conduct any new interviews or undertake other primary research for the encyclopedia. He had approximately 80 issues of the magazine from which to draw. He also relied on other books about the songwriter, especially Meryle Secrest’s 1998 biography Stephen Sondheim: A Life and Sondheim’s own volumes of collected, annotated lyrics, Finishing the Hat (2010) and Look, I Made a Hat (2011).

Also included in the encyclopedia is work of another writer. Mark Eden Horowitz had written a series of 10 in-depth explorations for The Sondheim Review, entitled “Biography of a Song.” Among them were investigations of such titles as “A Little Priest” and “Losing My Mind.” Pender includes somewhat condensed versions of Horowitz’s analyses in the encyclopedia.

As work on the project continued, Pender discovered some—but not many—Sondheim-related topics for which he felt the need to dig more deeply. For instance, he’d known that Sondheim had gone to Hollywood to write teleplays for the TV sitcom Topper early in his career. Pender researched the Topper experience in greater depth for his book. He also paid closer attention than before to Sondheim juvenilia and to unproduced Sondheim shows.

The author occasionally reached out to the man himself while assembling the book. And he shared the main biographical entry with Sondheim, to ensure he’d eliminated factual glitches. He had begun a working relationship with his subject while editing The Sondheim Review, and in 2005 the two men had first taken the stage together for a public interview at a business conference:

“The first time I would meet him was just moments before we walked onstage together to have a conversation. We were at a supper club in the Theatre District, and it went quite well. I’d actually asked him, in advance, if he’d like me to share some possible questions and have him pick what we would do. He said no—he really preferred to let it be more spontaneous and off the cuff.”

Sondheim and Cabaret

Pender stresses that The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia is not a coffee-table book, despite its voluminousness. It’s primarily meant to be a research tool. There are plenty of photos, he notes, but they’re black-and-white. “There’s a lot more text than there is imagery.”

Maybe because I am interviewing Pender for bistroaward.com, he seems eager to explain that there is plenty in the book that will appeal to cabaret artists and audiences. Aside from the inclusion of the Horowitz material, there are detailed song lists and analyses. I asked him whether there are parts of the Sondheim catalog that have been overlooked by club performers and recording artists.

He points to the score of Saturday Night, the 1954 musical that was not fully produced until the 1990s. That show’s songs, he says, “have a youthful and bouncy sound to them, because—well—he was a youthful and bouncy guy at the time.” Pender also recommends selections from Evening Primrose (1966) as well as some of the epistolary songs (or song-like passages) from the 1995 musical Passion, such as “Happiness” and “I Read.” (Actually, at least two Primrose songs—”Take Me to the World” and “I Remember”—already turn up with some regularity in NYC cabaret settings and in recordings.)

Now that the book has gone to press, does Pender wish to write about absolutely anything other than Sondheim, going forward? Not necessarily, he says. He anticipates writing another volume on some aspect of the Sondheim career. But it will undoubtedly be something on a smaller scale than the encyclopedia.

“I [now] have a more profound admiration [for Sondheim] and his work,” he says, “and the fact that he is still a relatively active—at least, as active as a 91-year-old man could be—creator. I remain as interested as ever in the work that he is doing.”

Note: In order to receive a 30% discount on The Sondheim Encyclopedia, Pender advises purchasing the volume directly from Rowman & Littlefield and entering the code RLFANDF30.

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.